Illustration of small piggy banks and large piggy bank balancing on a seesaw. | © shutterstock.com

Illustration of small piggy banks and large piggy bank balancing on a seesaw. | © shutterstock.com

The resilience of the Chinese banking system has been a subject of scrutiny over the past decade due to its individual characteristics, such as concentration, rapid asset growth, importance of shadow banking, opaque interconnectedness of financial firms, and the increased international clout of Chinese banks. The rapid expansion of the Chinese stock market poses opportunities and risks for international investors and greatly affects the performance of emerging markets, as benchmarked by common indices such as the MSCI EM.

In our paper, we shift focus from the largest, state-owned, and globally important banks, to the relatively smaller financial institutions and examine whether they contribute significantly to the systemic risk and interconnectedness of the Chinese banking sector. We also examine if three often-discussed sources of fragility—increased housing prices, economic policy uncertainty, and shadow banking—contribute to the magnitude of systemic risk in banks. We find that systemic risk has been persistently rising after the global financial crisis, with smaller institutions, in our sample covering about 50% of total banking assets, contributing more than 40% to total systemic risk in 2017–18. Our results show that increased housing prices, policy uncertainty, and shadow banking serve as a cause of systemic risk in the long and short runs. Shadow banking also contributes to the increase in housing prices. Finally, smaller banks appear to be more interconnected than their large counterparts and have greater influence than previously believed.

We measure systemic risk by estimating SRISK (Brownlees and Engle, 2016) for a representative sample of 17 listed Chinese banks, using the MSCI EM index as a market performance benchmark. We discuss the evolving interconnectedness of banks using a Granger causality network approach (Billio et al. 2012) and infer long- and short-run causality between systemic risk and explanatory factors from a series of vector error correction models. To measure policy uncertainty, we use the EPU and Trade Policy Uncertainty Index (Baker et al 2016), which covers business and economics news published in the Hong Kong–based South China Morning Post. The EPU indices, based on the frequency and coverage of business and economics articles in news outlets, have recently become popular as indicators of public sentiment, since they represent qualitative rather than quantitative shifts. For shadow banking, we move away from using entrusted loans as proxy (Allen et al. 2019) and instead select the more inclusive “Bank Shadow” and “Traditional Shadow Banking” measures proposed in Sun (2019). Traditional Shadow Banking captures credit creation by non-bank financial intermediaries through money transfer, while Bank Shadow captures money creation by banks through accounting treatments that generate liabilities and moves beyond traditional loans. Housing prices are proxied by the Real Residential Property Prices index for China from FRED.

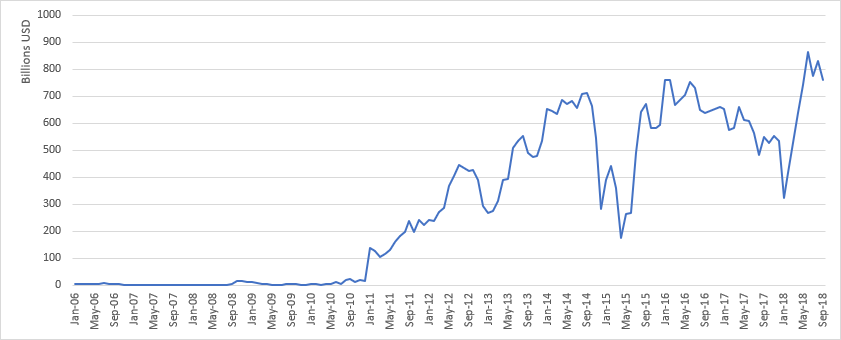

(a) Aggregate SRISK 2006 – 2018

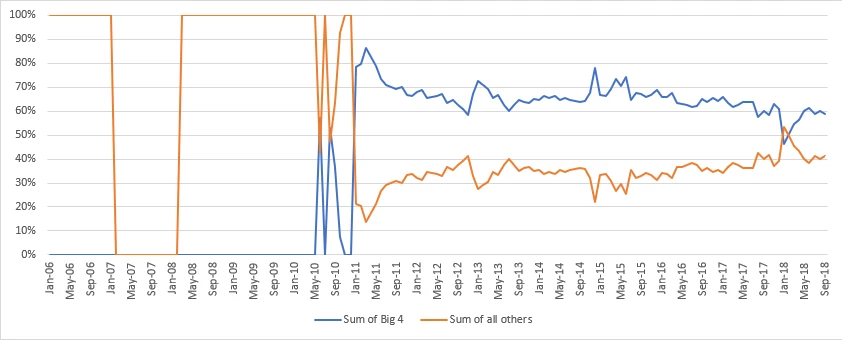

(b) Group contributions (%) to total SRISK of the Big Four and all other banks

FIGURE 1

Figure 1(a) shows the steady increase in total systemic risk after 2011. The Chinese banking system was resilient to the direct financial effects of the 2008–09 global financial crisis, largely because it was focused on a strongly growing domestic market and had little exposure to overseas wholesale funding markets. The large surge in SRISK during 2011–12 coincided with the end of the 2008 economic stimulus package, which led to a surge in credit volume and asset prices, including housing prices. The 2015 and 2016 Chinese stock market crashes were also associated with the large SRISK increase between May 2015 and August 2016. The post-crisis expansion of the Chinese housing and shadow banking sectors has been well documented, for example, by Lai and Van Order (2019) and Ding et al. (2017).

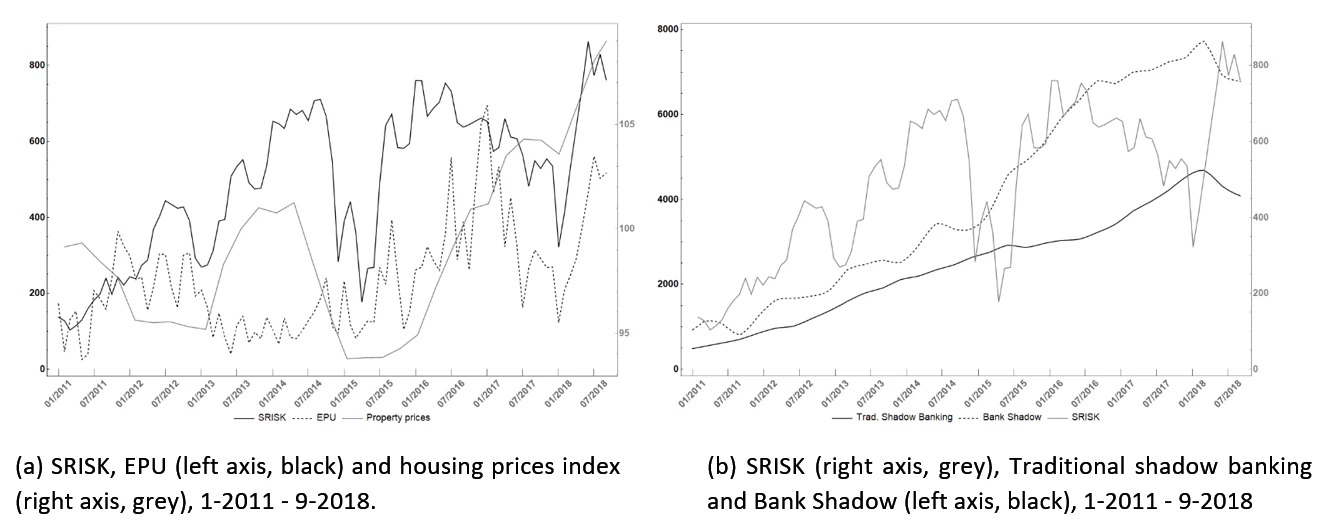

Economic policy uncertainty and housing prices affect systemic risk in the long and the short runs, while both shadow banking measures influence systemic risk in the long run. Notably, systemic risk does not seem to affect property prices or Bank Shadow, but there is a two-way influence for Traditional Shadow Banking and policy uncertainty. Shadow banking affects housing prices, but not the opposite. This shows how the financing of the Chinese housing market has relied on liquidity providers other than banks. When all factors are taken jointly into account, we observe similar relationships. The four indicators do not simply increase together (figure 2), but each of the three factors contributes to the rise in systemic risk and is linked with the rest. The intuition that housing prices, shadow banking, and uncertainty cause systemic risk for banks and feed into each other appears to hold for China.

FIGURE 2

Figure 1(b) compares the systemic risk contribution of the four biggest banks (Bank of China, Agricultural Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and China Construction Bank) with that of all other banks. From an 80%–20% split in 2011 in favor of the Big 4, the difference has receded to 60%–40% in 2018, which highlights the increased importance of smaller banks. The bank that influences the most other firms is China Merchants Bank, which affects 13 other firms, followed by China CITIC Bank (12), China Everbright Bank (11), and Agricultural Bank of China (11). China Everbright Bank (16), Bank of Nanjing (16), Ping An Bank (15), and Chongqing Bank (14) have the highest number of total connections. This demonstrates that smaller firms have not only become more important individually, but also are able to exert significant sectoral influence. Although we do not disregard the capacity for intervention of Chinese regulators, our results point toward an increasing vulnerability of China’s banking system due to contagion effects.

An international investor should be concerned about the influence of smaller Chinese banks on financial stability and take their systemic and individual riskiness into account. Their increased exposure and connectedness may trigger a systemic event with wider repercussions, significantly larger than their individual size. Although state ownership may prevent a bankruptcy similar to that of Lehman Brothers, our findings suggest that the overall cost of distress may be higher than commonly assumed. Our main policy suggestion is that further regulatory changes need to focus not just on the systemically important largest institutions but also on smaller banks.

References

Allen, F., Qian, Y., Tu, G., Yu, F., 2019. Entrusted loans: A close look at China's shadow banking system. Journal of Financial Economics 133 (1), 18–41.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., 2016. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131 (4), 1593–1636.

Billio, M., Getmansky, M., Lo, A. W., Pelizzon, L., 2012. Econometric measures of connectedness and systemic risk in the finance and insurance sectors. Journal of Financial Economics 104 (3), 535–559.

Brownlees, C., Engle, R. F., 2016. SRISK: A conditional capital shortfall measure of systemic risk. Review of Financial Studies 30 (1), 48–79.

Ding, D., Huang, X., Jin, T., Lam, W. R., 2017. Assessing China's residential real estate market. IMF Working Paper, 17/248.

Lai, R. N., Van Order, R. A., 2019. Shadow banking and the property market in China. International Real Estate Review, forthcoming, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2788012.

Sun, G., 2019. China's shadow banking: Bank's shadow and traditional shadow banking. BIS Working Papers, No 822.

Join the Conversation