The global financial crisis made us rethink financial sector regulation and supervision. As part of this process there has been a renewed interest in the institutional structure of financial services supervision. This includes reflections on the differences in these structures across countries, their development over time and their relative performance in the run-up and during the crisis. Several important questions have arisen: (i) why supervisory structures for the financial sector differ so much across countries, especially in the extent to which they integrate the microprudential supervision of financial subsectors (banking, insurance, capital markets), (ii) why some countries have chosen to institutionally integrate microprudential and macroprudential supervisions while other keep those separated, (iii) why business conduct supervision has been introduced in some countries and not others, and how does it interact with institutions that support prudential supervision? From a development perspective, one may also want to ask the questions of: (i) what models have the emerging market economies and developing countries chosen to follow and why, and (ii) is there a prevailing trend toward certain benchmark models that countries have followed according to their financial system typology?

In a recent paper, we analyze the evolution of prudential and business conduct supervisory structures for financial services over the past decade for 98 high and middle income countries, and identify factors that could be driving their evolution. We compiled two new datasets, one on prudential supervision structures and another on business conduct supervision structures. These datasets enable us to study changes and differences in supervisory structures over time and across countries. The dimensions of supervisory structures that we consider account for the degree of integration of microprudential supervision, including the extremes of different rules and different supervisors for each type of intermediary versus common rules for similar financial activities regardless of which intermediary carries them out. Further, we distinguish between the approaches of placing an integrated supervisor within a central bank or under a separate (financial supervisory) authority. We thus consider the proximity of microprudential and macroprudential supervision. Moreover, we gauge the pursuit and integration of business conduct supervision as a complementary function to prudential supervision.

Main Data Trends

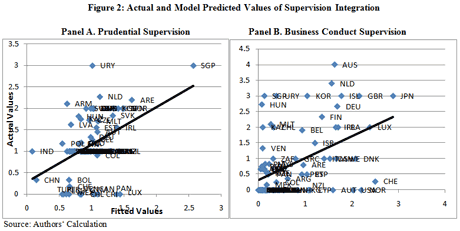

The historical data over the past decade show a trend toward greater integration of prudential supervision both across financial subsectors and, to some extent, across microprudential and macroprudential supervision. The proportion of countries that preserved the traditional model of institutional regulation decreased from 62 percent in 1999 to 44 percent in 2010. At the same time, the proportion of countries that integrated microprudential supervision in a Financial Supervisory Authority (FSA) increased substantially from 11 percent in 1999 to 25 percent in 2010. Moreover, the percentage of countries that integrated the microprudential supervision under the central bank (CB), and thus also introduced integration of microprudential and macroprudential supervision, increased from three percent in 1999 to eight percent in 2010. The proportion of countries that chose to integrate in a FSA thus outpaced those that integrated in the CB, both in more and less financially developed economies (as gauged by credit to GDP). Figure 1 (panel A) illustrates the changes in prudential supervision structures during the period 1999-2010.

As regards business conduct supervision, we observe an important increase in the proportion of countries that introduced its enforcement during 1999-2010. Figure 1 (panel B) shows the trends in business conduct supervision. Almost fifty percent of the countries that did not have holistic business conduct supervision for financial services in 1999 have adopted it during the past decade. In half of the cases, the change was accomplished by integration of the function into the FSA or the CB, or by adoption of the “twin peak” model.

Choice of Supervisory Structures and Country Typology

The potential determinants of a country’s choice for supervisory institutions that we considered in the analysis can be divided into four sets:

- countries’ general and economic development indicators;

- political and governance indicators, such as the quality of governance and the autonomy of the central bank;

- financial sector development indicators, such as the depth and complexity of the financial system and banking sector characteristics, and

- the number of past financial crises experienced by a country.

We performed two separate analyses, one focusing on prudential supervision, and the other on business conduct supervision. Building on the identified significant determinants of changes in supervisory structures over time and across countries, we draw preliminary conclusions about possible country benchmark models according to the country typology.

We find that as countries advance to a higher stage of economic development, they tend to integrate to a greater degree their financial sector supervisory structures. Also, improvements in overall public governance drive countries to adopt more integrated supervisory arrangements. Greater independence of the central bank, which is often involved in supervision of banks, could entail less integration of prudential supervision, but not necessarily business conduct. Further, small open economies tend to opt for more integrated structures for financial sector supervision, especially on the prudential side, although a progressively higher degree of openness could coincide with less integration of business conduct supervision.

Financial development is an important factor behind countries’ choice of a particular structure of financial services supervision. The size of the banking sector positively influences the integration of both prudential and business conduct structures. In contrast, strong development of the non-bank financial sectors including capital markets and the insurance industry makes countries opt for a less integrated prudential supervision structure. In other words, the larger and more developed the non-banking financial sectors, the less beneficial or more difficult it could be for countries to implement prudential supervisory integration. Concerning banking sector characteristics, countries with banking sectors that have been more exposed to aggregate liquidity risk tend to integrate their prudential supervision to a higher degree. For business conduct supervision, the lobbying power of the banking sector, approximated by banking sector concentration and profitability, is associated with a negative impact on pursuing business conduct. Finally, the number of past financial crises strongly increases the probability that a county will opt for integration of both prudential and business conduct supervisory structures. There seems to be a perception that supervisors are better equipped to effectively deal with episodes of systemic financial distress under integrated supervisory structures.

Historical Benchmark and Current Supervisory Structures

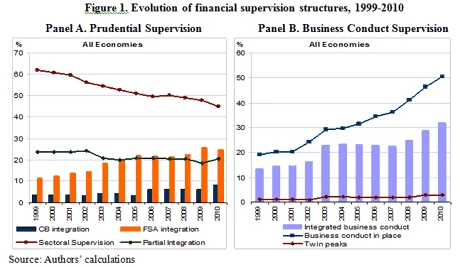

We also benchmark the existing supervisory structures of the individual countries in our sample against the model-predicted degree of supervisory integration. This is to illustrate whether a country’s choice of a particular supervisory structure followed the prevailing global trends based on its typology. For prudential supervision, this comparison is depicted in Figure 2 (panel A) along with the regression line showing in the north-west corner countries with supervisory structures less integrated than predicted by our model and, in the south-east corner, countries with supervisory structures more integrated than our model predicts. A number of countries, in particular, Luxemburg, Panama, Costa Rica, Canada, and Chile, are expected to have implemented prudential supervisory structures characterized by greater integration given the experience of their peers. On the other hand, there are several countries, including Armenia, Czech Republic, Uruguay, Netherlands, Slovakia and Poland that integrated their prudential supervisory structures more than predicted by their country and financial system characteristics. For some of the countries in this category, a fashion effect may be at work. The literature refers to the fashion effect (or bandwagon effect) when reformers were inspired by the type of changes in governance arrangements introduced by earlier reformers (neighboring or role-model countries) rather than the effectiveness of an integrated supervisory structure based on their economic system and financial sector characteristics.

For business conduct supervision, the comparison of existing vs. model-predicted supervisory structures is illustrated in Figure 2 (panel B). This comparison suggests that the implementation and integration of business conduct supervision, including mechanisms for its enforcement, in countries such as the US, Austria, Cyprus, and New Zealand is less advanced than predicted by our model. In contrast, there are no notable over-performers pointing to the fact that implementation of holistic business conduct supervision and consumer finance protection is a relatively new area for policymakers. Nevertheless, some countries, including Singapore, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Uruguay, Kazakhstan, and Malta, have shown a greater tendency to address business conduct supervision and consumer finance protection in a more holistic way than their experience, country typology and financial sector characteristics would suggest.

Join the Conversation