How much does management matter for economic performance? Despite a large industry of business schools, consulting firms, and airport books purporting to teach you the secrets of good management over the course of your next flight, the answer until very recently has been “we don’t know”. In a recent review, Chad Syverson goes as far as to say “no potential driving factor of productivity has seen a higher ratio of speculation to empirical study”.

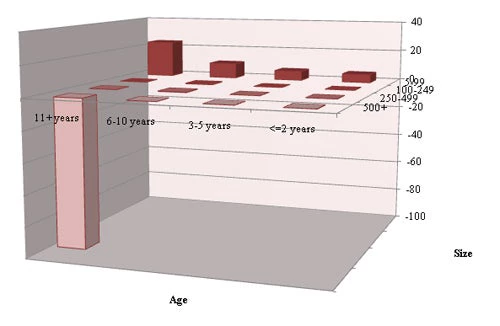

Together with colleagues from Stanford and Berkeley, I have been working for the last couple of years to try and understand how much management matters by means of a randomized experiment among textile factories in India. In common with most firms in developing countries, the firms (with 300 workers on average) we were working with did not collect and analyze data systematically in their factories, had few systems for regular maintenance and quality control, had weak human resource systems for promoting and rewarding good performers, and had little control over inventory levels. The result was a high level of quality defects, large stockpiles of unorganized inventories, and frequent breakdowns of machines. 20 percent of the labor force was occupied solely in checking and repairing defective fabric (see picture).

Firms were then randomly divided into treatment and control groups. The treatment group received five months of intensive management training by Accenture consulting’s Mumbai office. The consulting was designed to help firms adopt standard quality, inventory, and production control systems which are standard in almost all U.S., European, and Japanese firms. The control group received diagnostic visits which identified problems, but did not receive detailed implementation help from the consultants.

Detailed data on these plants allowed us to track the changes in performance as management improved, and to thereby identify the causal impact of better management. The figure below illustrates the results for quality defects, which are normalized to be 100 before the intervention. We see the defect rate fall quickly in the treatment plants relative to the control plants, and continue to stay lower once the implementation ends.

Similarly we find inventory levels fall, output improves, and productivity rises by 10%. As firm owners get better control and monitoring over what is happening in their factory, they are willing to delegate more decision-making to mid-level management, increasing decentralization.

Estimating the increase in profits from these improvements is difficult given the opaqueness of firm records in this respect, but our current estimates suggest an annual increase in profits of about $200,000. The market price of the consulting services we offered would be approximately $250,000. Thus if these improvements can be sustained, the return on better management would be 80%. This is in line with the high returns to capital found in microenterprises in some of my other work, and suggests that better management is certainly worth investing in.

So what can policymakers do to help firms to improve management? Funding better business schools and developing the local consulting market is one avenue. However, many of these practices may be better learned on-the-job than in school, and so making it easier for well-managed multinationals to enter and provide opportunities for local workers to gain experience working in well-managed companies is also important.

Further Reading:

Ray Fisman provides a nice summary of this research in his Slate column

A two page summary of preliminary findings is available in the Finance & PSD Impact Note series

A draft version of the paper is available on Nick Bloom’s webpage, along with a video

Join the Conversation