Paige Donnelly

will graduate in Political Science and Arabic at Davidson College this May. She grew up in the Middle East and Africa, and has studied in Peru, Jordan, and Morocco. Her writing has been published in The Washington Post, American Interest, Survival, and the Los Angeles-based Arab arts magazine, Al Jadid. After graduation, she plans to move to Beirut to continue supporting Syrian artists.

She can be reached at paigedonnelly@gmail.com.

Classical music welcomed me into Fadi Al Hamwi’s flat in the Gemmayze neighborhood of Beirut. His room was simple and distinctive. Instead of furniture occupying the space, he had lined it with art. Music swelled around us and half-finished, dramatic life-size paintings leaned against the walls.

Classical music welcomed me into Fadi Al Hamwi’s flat in the Gemmayze neighborhood of Beirut. His room was simple and distinctive. Instead of furniture occupying the space, he had lined it with art. Music swelled around us and half-finished, dramatic life-size paintings leaned against the walls.

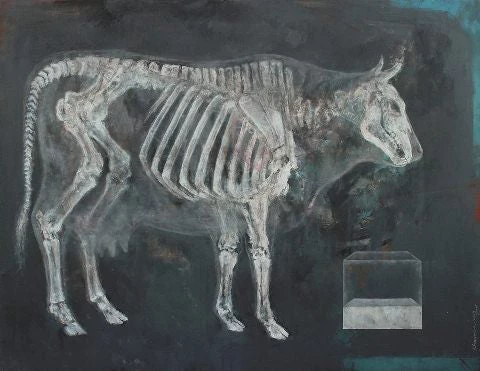

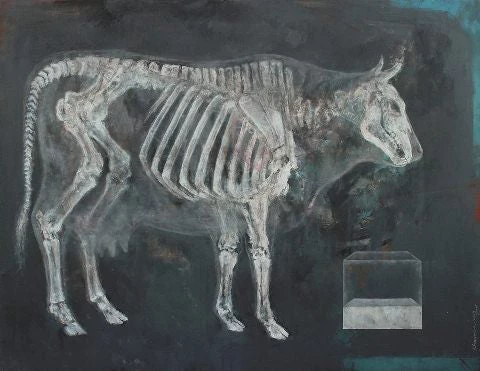

Fadi, a 27-year-old painter from the Syrian capital of Damascus, had moved to Beirut almost two years ago. On the walls were a series of X-ray portraits, mostly of animals. He said his art explored the lack of humanity in the Syrian war, exposing men and woman stripped to the structure of their bones.

Making my way back through the festive and whimsical streets of Gemmayze, full of artists and galleries showing their work, I was only 40 or so miles from the Syrian border. Gemmayze, many residents told me, was the place in Beirut that most conjured up memories of the old city of Damascus. Many Syrian artists, like Fadi, have either moved into this neighborhood or spend their afternoons in coffee shops, perhaps subconsciously searching for reminders of home.

That day I, too, was searching, though for the human element in the Syrian conflict.

For me, Fadi and other Syrian artists living in exile in Lebanon opened a window into a country veiled by the cold statistics of death tolls and displaced populations. To me, these artists offered a fresh and human perspective on the conflict: they gave a face to war.

In tribute to the bombing of his brother’s home, Fadi had created an installation of broken blocks with a small TV placed on top. “I felt like a criminal,” Fadi told me. Yet, he said, breaking the concrete blocks and turning useful material into rubble was a necessary step to relive the destruction of war.

Emphasizing its primitiveness, Fadi strategically placed the installation in the stark interior of the Artheum gallery in Beirut last October during the Syrian Contemporary Art Fair. The audience, in order to see what was on the TV, had to walk inside the rubble. There, they found themselves shown on the TV surrounded by the broken blocks. Fadi said he wanted them to feel--if only for ten seconds-- what it was like to be a victim of the Syrian conflict.

Emphasizing its primitiveness, Fadi strategically placed the installation in the stark interior of the Artheum gallery in Beirut last October during the Syrian Contemporary Art Fair. The audience, in order to see what was on the TV, had to walk inside the rubble. There, they found themselves shown on the TV surrounded by the broken blocks. Fadi said he wanted them to feel--if only for ten seconds-- what it was like to be a victim of the Syrian conflict.

I met another half-dozen Syrian artists in Beirut over a week in the city.

For most, their art reflected elements of the conflict, while for a few, their art skirted the issue, a deliberate choice, they said, reflecting a desire to rediscover the beauty of Syria.

Many of these artists had stayed for a month at Art Residence Aley, an NGO based in the hills above Beirut that offered artists a safe haven and a creative outlet, at least for a few weeks.

One of the goals of the organization is to connect audiences far beyond the war zone to what is happening inside Syria today through the lens of artists.

Some of what I saw in Beirut, you can see in the lobby of the World Bank’s headquarters for the next few weeks. I hope the art will give people a reason to look again at what is happening to people caught in a war and not to look away but imagine being there.

Classical music welcomed me into Fadi Al Hamwi’s flat in the Gemmayze neighborhood of Beirut. His room was simple and distinctive. Instead of furniture occupying the space, he had lined it with art. Music swelled around us and half-finished, dramatic life-size paintings leaned against the walls.

Classical music welcomed me into Fadi Al Hamwi’s flat in the Gemmayze neighborhood of Beirut. His room was simple and distinctive. Instead of furniture occupying the space, he had lined it with art. Music swelled around us and half-finished, dramatic life-size paintings leaned against the walls.

Fadi, a 27-year-old painter from the Syrian capital of Damascus, had moved to Beirut almost two years ago. On the walls were a series of X-ray portraits, mostly of animals. He said his art explored the lack of humanity in the Syrian war, exposing men and woman stripped to the structure of their bones.

Making my way back through the festive and whimsical streets of Gemmayze, full of artists and galleries showing their work, I was only 40 or so miles from the Syrian border. Gemmayze, many residents told me, was the place in Beirut that most conjured up memories of the old city of Damascus. Many Syrian artists, like Fadi, have either moved into this neighborhood or spend their afternoons in coffee shops, perhaps subconsciously searching for reminders of home.

That day I, too, was searching, though for the human element in the Syrian conflict.

For me, Fadi and other Syrian artists living in exile in Lebanon opened a window into a country veiled by the cold statistics of death tolls and displaced populations. To me, these artists offered a fresh and human perspective on the conflict: they gave a face to war.

In tribute to the bombing of his brother’s home, Fadi had created an installation of broken blocks with a small TV placed on top. “I felt like a criminal,” Fadi told me. Yet, he said, breaking the concrete blocks and turning useful material into rubble was a necessary step to relive the destruction of war.

Emphasizing its primitiveness, Fadi strategically placed the installation in the stark interior of the Artheum gallery in Beirut last October during the Syrian Contemporary Art Fair. The audience, in order to see what was on the TV, had to walk inside the rubble. There, they found themselves shown on the TV surrounded by the broken blocks. Fadi said he wanted them to feel--if only for ten seconds-- what it was like to be a victim of the Syrian conflict.

Emphasizing its primitiveness, Fadi strategically placed the installation in the stark interior of the Artheum gallery in Beirut last October during the Syrian Contemporary Art Fair. The audience, in order to see what was on the TV, had to walk inside the rubble. There, they found themselves shown on the TV surrounded by the broken blocks. Fadi said he wanted them to feel--if only for ten seconds-- what it was like to be a victim of the Syrian conflict.

I met another half-dozen Syrian artists in Beirut over a week in the city.

For most, their art reflected elements of the conflict, while for a few, their art skirted the issue, a deliberate choice, they said, reflecting a desire to rediscover the beauty of Syria.

Many of these artists had stayed for a month at Art Residence Aley, an NGO based in the hills above Beirut that offered artists a safe haven and a creative outlet, at least for a few weeks.

One of the goals of the organization is to connect audiences far beyond the war zone to what is happening inside Syria today through the lens of artists.

Some of what I saw in Beirut, you can see in the lobby of the World Bank’s headquarters for the next few weeks. I hope the art will give people a reason to look again at what is happening to people caught in a war and not to look away but imagine being there.

Join the Conversation