Youth exclusion- is a challenge of staggering proportions in the post-2015 development agenda. Since 2011, disenchantment among the largest youth cohort in history has channeled itself into movements challenging the status quo in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Europe, and Latin America. Popular protests have been called not just for jobs but for changing the old order, for a voice on policies that impact the future of youth, and for justice, freedom and dignity.

Youth exclusion- is a challenge of staggering proportions in the post-2015 development agenda. Since 2011, disenchantment among the largest youth cohort in history has channeled itself into movements challenging the status quo in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Europe, and Latin America. Popular protests have been called not just for jobs but for changing the old order, for a voice on policies that impact the future of youth, and for justice, freedom and dignity.

Theirs has been a wake-up call heard around the globe. Of the estimated 1.5 billion young people in the 12 to 24 age bracket, more than 1.3 billion live in developing countries. [1] While the ratio of youth to adult unemployment is significant, the Not in Education Employment or Training (NEET) indicator is a more comprehensive assessment of inactivity as it includes discouraged and disengaged in addition to unemployed youth. More than a quarter of youth around the world aged 15 to 24 are considered ‘inactive’, with the highest rates in Europe and Central Asia and MENA. [2]

A number of governments and institutions like the UN, EU, OECD, the World Economic Forum, members of the private sector, and foundations, now see youth inactivity and inclusion as a priority. The Report of the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda [3] saw for the first time a quantifiable youth development target to decrease the number of young people not in education, employment or training by x %. What does this mean for a renewed World Bank?

The recent brainstorming on “ Unbundling the Youth Inclusion Agenda” at the World Bank stressed the importance of an integrated approach on youth issues to reach the goals of reducing poverty and promoting shared prosperity, and the need to develop a common framework on youth inclusion. This was the first time staff from across the Bank met to unbundle the many dimensions of youth inclusion, along, with academic experts, the private sector, civil society, and youth community representatives.

The brainstorming session offered an opportunity to unbundle youth inclusion into several dimensions: economic opportunities, such as income, education, employment, and inactivity; social such as demography, gender, ethnicity, social networks, and disability; political such as security, conflict and violence, civic engagement, trust in institutions, participation in decision making, and voice; and cultural such as religion, identity, values and aspirations.

Findings from a Gallup World Poll 2013 emphasized the need to go beyond the metrics of income and unemployment. It compared perceptions from youth on standards of living, their own evaluation of their lives, social well-being, community attachment, volunteering, and their degree of trust in national government. The MENA and Sub-Saharan African regions were consistently classified as the bottom performers. In terms of life evaluation, their youth were the least likely to be classified as thriving. MENA youth reported worse standards of living in 2013 than in 2012, and less confidence in their national governments than African youth did.

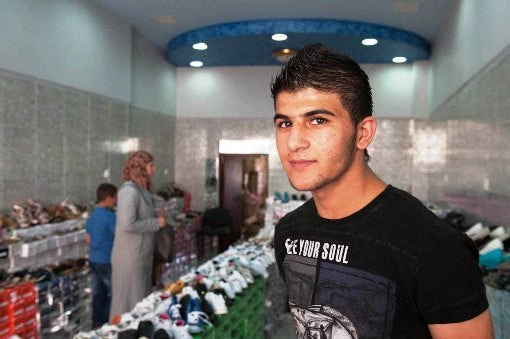

It was stressed that youth is a social category with an identity that cuts across a range of ideological, ethnic, sectarian, gender, and national identities. Youth today encompass a contested patchwork of identities, as well as multiple lives, for example at home within the family, in the public sphere, and in the street.

Interventions that address articulate urban, middle class youth should no longer be the priority: For lower income and less educated youth, especially the bottom 40%, the informal sector remains the main source of employment. This sector has thus to be part of the solution.

Local governments and communities are a critical channel for youth engagement and empowerment.. Youth-friendly services like life skills training, ICT and language skills, healthy lifestyles, peer mentoring, and sports can be provided in a more sustainable manner at this level. They have greater impact when delivered with youth participation and in partnership with local governments and communities. The need to only support interventions that are owned by young people and empower them was emphasized.

We need partnerships that include the private sector and civil society right at the beginning and not as an afterthought. We also need to systematically address critical constraints to youth development, such as labor market and business regulation, education, property rights and human rights, as well as the lack of voice in decision making. These are broader development challenges that indicate that the future of youth and their countries are intertwined.

The next steps suggested for the Bank are a thematic group centered around knowledge sharing, a working group across Global Practices to work towards a common framework on youth inclusion and to identify few countries where a more multidimensional approach could be taken to scale and replicated elsewhere.

[1] World Development Report 2007,

Development and the Next Generation, World Bank, 2006.

[2] World Bank. Human Development Network Statistics, 2013.

[3] A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies through Sustainable Development, Report of the Secretary-General’s High-level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, May 2013.

Join the Conversation