Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries differ from SMEs elsewhere in that they employ mostly expatriate workers and very few of their own nationals.

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries differ from SMEs elsewhere in that they employ mostly expatriate workers and very few of their own nationals.

How do we know this? We see it in the labor force statistics: The share of expatriates in the private sector labor force ranges from 80% to 98% in the six GCC countries— Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)— the lowest being in Oman and Bahrain, and the highest in Qatar and the UAE.

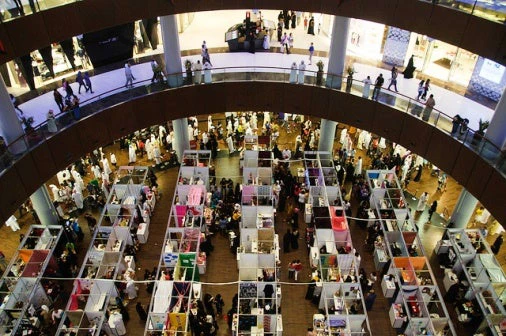

Indeed, if we go to the level of low-skill microenterprise, it would be accurate to say that almost the entire workforce is made up of expatriates. This is what we find in the thousands of small groceries, laundries, barbershops, and other retail businesses that line the side streets and alleys of all the major cities in the Gulf region.

This economic structure has come about because of open labor admission policies and generous compensation in the public sector. The open labor admission policies mean that private sector employers have access to a vast range of attractively-priced labor, primarily from South and Southeast Asia: So for every 10 jobs created in the private sector, eight or more go to expatriates. Nationals, meanwhile, gravitate towards the public sector because of the better pay and working conditions.

There is an additional complication: Sometimes, even the real owner of the SME (in the sense of being the person who advances the capital and acts as the entrepreneur) is an expatriate, while a national serves as a front man or woman for legal purposes, an arrangement known locally as “ tasattur” (loosely translatable as disguise or incognito).

This may be one reason why GCC commercial banks so rarely lend to SMEs. While the average share of bank loans to SMEs of their total loans is more than 26% in high-income OECD countries, it is only 2% in the GCC countries ( see here). Banks in the GCC not only face the same constraints to SME-lending that they face elsewhere—lack of collateral, informal or non-existent accounts, and weak business planning skills among applicants—but may also feel unsure of the true ownership of the projects for which loans are requested.

So what should an SME support strategy emphasize in the GCC context?

Firstly, instead of seeking to create more jobs for nationals (almost impossible given present labor market policies in the GCC), the main objective should be promoting entrepreneurship among nationals. This would involve focusing not so much on the financing needs of the applicant, but on his or her business potential. So the package of support should include mandatory training and in-workplace advisory services which would also help weed out the tasattur applicants.

Secondly, restrict financing to high value-added activities (e.g., projects relating to information technology, engineering and renewable energy). While these might generate fewer jobs than low productivity alternatives, they would be more likely to appeal to skilled nationals.

These aspects suggest that equity funds, rather than banks, may be better instruments of support for SMEs in the GCC. Governments could support such funds through financing, as well as the provision of training and incubation opportunities for the prospective entrepreneurs.

Join the Conversation