“How do you engage a country that may not agree with your climate agenda?”

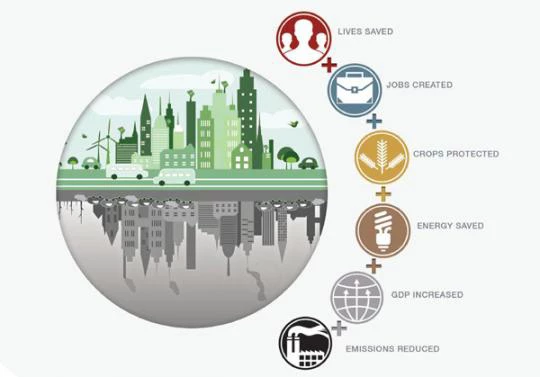

The question came last week, as I was sharing the findings of our recent report, Climate-Smart Development: Adding up the benefits of actions that help build prosperity, end poverty and combat climate change with students from the Williams College Center for Development Economics. I hope my talk answered her question. I pointed out that increasingly, decision-makers want to know if there are investment decisions they can make that address urgent development priorities and, at the same time, address the challenges of a rapidly warming world.

Three articles in the news this week reinforce the messages in our report and shed further light on the answer to her question. A pair of research papers point out that black carbon and ground-level ozone – air pollution associated with so-called short-lived climate pollutants, or SLCPs – are already reducing Indian agricultural yields by up to half, and that coal-fired power – a large source of air pollution including CO2 – is costing China 670,000 deaths each year. These are both prime examples of local development issues that present climate-smart investment choices. As governments search for solutions to their health and agriculture problems that are exacerbated by air pollution, they have two options: invest in smoke stack controls and other interventions that eliminate the air pollution causing crop loss and mortality, but keep churning out CO2, or invest in alternative energy sources and efficiency measures that will also reduce both forms of climate pollution.

How we answer these questions will make a significant difference in the coming decades. The New Climate Economy report points out that more than $90 trillion will be invested in cities, land-use, and energy infrastructure between now and 2030. These investments can be made in ways that are climate-smart or not. Unless economic analyses recognize the multiple local benefits to health, agriculture, and other areas, in addition to the avoided global climate impacts, governments likely won’t be in a position to see the full value of various climate-smart investment choices.

Another paper published this week speaks to the question of establishing development priorities in the context of rapid warming. It addresses the tradeoffs between reducing SLCPs that provide development benefits and near-term climate relief versus reducing CO2, which is the key to long-term climate stabilization. Some researchers have questioned whether the focus on SLCP reduction is detracting from action on CO2. This study points out that because SLCPs and CO2 often have many of the same sources, strong CO2 mitigation would get you many of the SLCP climate benefits. In addition, a strong-sustained investment in air pollution reduction would get you the rest of the benefit. The problem is that the world has not yet done enough to address the inexorable climb of CO2 emissions or to address the devastating air pollution affecting tens of millions of people on a daily basis.

Which brings me back to the Williams College student’s question. Perhaps focusing on the many benefits of reducing both greenhouse gases and SLCP emissions that go beyond climate is the best way to motivate action on both. This week’s news makes it clear that the multiple-benefits framework is not about convincing governments that they need to agree with a particular view of the climate agenda. Rather, this framework enables decision-makers to recognize that where development investments are going to be made (and $90 trillion worth are going to be made soon) there may be opportunities to provide some measure of simultaneous climate relief, for both the near-term and the long-term.

Join the Conversation