It does not happen often that one of the finest actors of our time tweets about a World Bank supported project and invites all his fans to have a look at the impressive pictures taken from space. In fact, I can’t remember having seen that before.

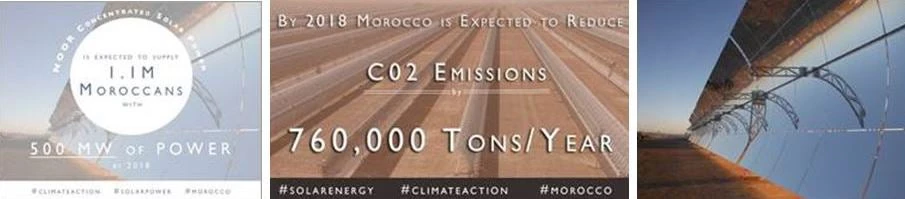

But this is what Oscar winner and climate activist Leonardo DiCaprio did a few months ago when the Noor Concentrated Solar Plant (CSP) in Morocco—the largest CSP plant in the world - was opened. Once finalized, in two years, it will provide clean energy to 1.1 million households. I visited the plant two weeks ago and it is truly an impressive site. The indirect benefits of the project might even be larger: it has advanced an important and innovative technology, it has driven down costs of CSP, and it holds important lessons for how public and private sectors can work together in the future.

I am proud that the World Bank, jointly with the African Development Bank and a number of foreign investors, supported this cutting-edge solar energy project. But it was made possible thanks to the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), which put in US$435 million to “de-risk” the investment, playing an essential role to kickstart the deal.

While at the CIF Trust Fund Committee in Mexico last week, I spoke with all its members, consisting of donor and developing countries, about the urgent need for action between now and 2020 as a direct consequence of the Paris Climate Agreement. Last year, developing countries prepared so-called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions laying out their pathways to a low-carbon and climate resilient future. The World Bank and other development partners are ready to help our client countries implement these plans urgently and effectively. A functioning global climate finance architecture is essential to help these countries reach their climate goals. Developing countries need to know that funding is available for these plans now and in the coming years.

Concessional financing is essential to unlock climate-smart investments which are deemed too risky for investors, and even in some cases for multilateral development banks. Well-targeted use of this type of financing is necessary to push new technologies, clean tech markets to commercialization, and to crowd in private sector financing, just like with the concentrated solar power project in Morocco. Concessional finance is also necessary to support investments in climate resilience and adaptation, especially in the poorest and most vulnerable countries.

It may sound abstract but well blended concessional finance leads to projects, for example, in roof-top solar energy, flood-proof roads and bridges, reforestation—all projects that have real, positive impacts on people’s lives.

The climate revolution we need, however, is not only about concessional financing. Perhaps even more importantly it’s about changing policies, practices and institutions, based on global and local experiences and lessons learned. For example, as we have recently seen in Zambia, well-structured renewable energy contracting based on good practices has led to very low bid prices.

In all of this, the Climate Investment Funds (or CIF), a US$ 8.3 billion fund founded in 2008, dedicated to climate-smart investments and implemented by the multilateral development banks, has been essential. It is a quiet, but very effective motor sitting in the middle of the climate financing architecture. It is an essential coordination mechanism for the most important players in this space, aligning them around country-driven climate investment plans and sharing lessons and experience across countries

The CIF has a strong record and has been transformational. For example, it has been a global leader in supporting geothermal deployment in 17 low and middle-income countries. It has enabled the Sere wind farm in South Africa, one of the largest wind energy complexes in Africa. It is supporting major solar power developments in Central America, jointly with IFC and the private sector. It made possible that climate resilient planning is central in all of Zambia’s national development planning. Thanks to its dedicated forest investment program, it will improve the land management of 27 million hectares of forests. Just to mention some examples of its impressive portfolio.

Perhaps more importantly, beyond the investment level, the CIF has influenced our way of working. It is the driver of the so-called "programmatic" approach, meaning broad-scale investments are paired with country planning, domestic policy changes and consultations with a wide number of stakeholders.

The climate finance architecture is evolving. Last week in Mexico, we agreed that all the main actors—the CIF, the MDBs, GEF, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and others—need to intensify their collaboration. The World Bank Group is working with the GCF, and eventually, we hope that we will be able to partner with the GCF to support client country projects. To enable the GCF to evolve into an effective partner for transformational investments, we look forward to GCF taking greater risks to crowd in financing for key projects and adopting a more programmatic approach to investments.

In Mexico, I also saw overwhelming support from developing country and civil society members about the work that the CIF is doing and strong support to continue this role. One after another, participants described the transformational impact that the CIF has had in their countries. The Direct Grant Mechanism under the CIF is a one-of-a-kind program designed for Indigenous Peoples and forest communities to support them in forest management and reforestation efforts. The CIF was also key in mainstreaming gender policies in climate investments, not only in their own investments but across all funding provided by the World Bank Group. It has helped to formulate gender-sensitive approaches across investment portfolios through technical support, knowledge generation and program learning.

Our meeting in Mexico recognized the urgency and the ambition of the changes necessary to set us on a realistic path to meet even the 2 degree objective of the Paris Climate Agreement. We have the opportunity to refine what the CIF does, but the role of and need for the CIF is absolutely key. The obligation and opportunity is on us. If we look back on this in 2020; did we fiddle while Rome burned or did we seize the opportunity and set the world on a low carbon and climate resilient future?

Join the Conversation