Energy poverty cripples development prospects. Where people don’t have access to modern energy services, like reliable electricity, their ability to earn a livelihood is sabotaged. That’s why UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has called — admirably — for “a revolution that makes energy available and affordable for all” in 2012, designated the International Year of Sustainable Energy for All.

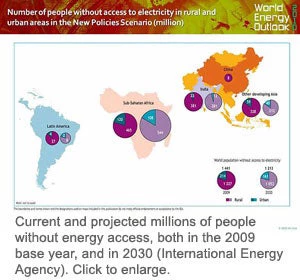

This sense of urgency is needed, especially in Africa, as current International Energy Agency forecasts project that the number of people in sub-Saharan Africa without access to modern energy services will grow by almost 100 million between now and 2030 (see the figure below).

The “revolution” in access is essential, Ban Ki-moon said, not just to reduce poverty, but also to stop climate change, improve global health, and empower women.

Expanding access to energy is also central to the World Bank Group’s strategy to help countries end poverty.

Our tools in this battle are changing, however. Off-grid lighting — from solar lanterns to solar home systems, to generators running on combusted or gasified biomass — as well as some new and effective grid extension and micro-, mini-, and regional grid systems are all showing promise. I have discussed these in previous blog posts: see “Billions Without Power Can Now Think Low Carbon,” “Kenya Steps Ahead Into Solar Future,” “Clock Is Ticking on COP 17 and Energy Poverty,” and “Green Jobs in Local Manufacturing Can Build Prosperous, Clean-Energy African Future.” These different sources and technologies need to be refined and adapted to meet local conditions, as well as integrated into national and regional programs.

Are these new approaches having an impact? How much progress have we made in reversing the disturbing trend of increased numbers without access to modern energy services, or too-slow progress to expanding access? And, where are we in terms of funding these innovations?

To help inform the design of appropriate and effective policies to reduce energy poverty, a team of researchers from a range of international agencies, universities, and the private sector, released a new paper Monday, July 18, “Informing the Financing of Universal Energy Access: An Assessment of Current Flows.”

This paper presents an analysis of current macro financial flows in the electricity and gas distribution sectors in developing countries. Building on the methodology used to quantify the flows of investment in the climate change area, the paper includes data compiled from countries’ respective national expenditures on energy access, as well as development aid, and foreign direct investment contributions to expanding such access.

These high-level and aggregated investment figures offer policy-makers a big-picture sense of scale, but they are not sufficient to design financial vehicles, and they tend to mask variations among sectors and countries, as well as trends and other temporal fluctuations. Nonetheless, for the poorest countries, the data tell us that current flows so far are only about 20 percent of what’s needed to provide a basic level of access to clean, modern energy services to the “energy poor.”

We have grown accustomed to bad news on the climate and energy-for-development investment front, with exciting commitments to ‘fast start’ funds and to a global Green Fund targeted to reach $100 billion per year by 2020. So far, however, it is not clear if, when, and how rapidly these funds will be banked and made available.

The good news is that while hundreds of billions of dollars are estimated to be needed—perhaps $400 – $600 billion to address climate issues— less than one-tenth of that would significantly address, if not fully tackle, energy poverty.

The way to a solution is not just more money, but putting the money in the right place. So far, the data do not indicate that funding levels and energy access needs are being logically or consistently deployed. In data gathered by UNIDO (see page 15 of the paper referenced above), we find no consistent correlation between funds spent and the degree of energy poverty.

We know that funds spent on energy access have far-reaching impacts not only for economic growth and development, but also on the quality of life, economic empowerment of rural communities, on women, and on a reduced pressure on the local ecosystems that are critical to human and ecological health.

Clearly it is time to get on with the job of both raising these funds, but also making clear that energy access is a both a basic service that individuals and households need, as well as an essential contribution to national economic health.

Join the Conversation