Nero fiddled while Rome burnt. The band played while the Titanic sank. And today, it could be said that a cacophony of international climate voices muse in discord, while the sea level rises. These were my thoughts when colleagues and I received the news of the latest report by Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP), the scientific arm of the eight-nation Arctic Council, asserting that sea-level rise could reach 1.5 metres by 2100. This is from the executive summary of their report while the full version is awaited. It is a sharp contrast to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC’s) 0.58 metres in its worst case scenario. This latest warning from the Arctic Council must now serve as a new score, with an urgent tempo, with which to conduct, orchestrate and harmonize international efforts towards rapid action on climate change.

The IPCC’s 2007 findings on sea level rise in its fourth assessment report was an important milestone helping to mobilize political momentum and to build a robust international process around the climate challenge. But at the time, as related to us in a recent presentation byDr. Robert Bindschadler, Emeritus Scientist on Hydrospheric and Biospheric Sciences at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, ice sheet dynamics were not accounted for in these projections.

The IPCC’s 2007 findings on sea level rise in its fourth assessment report was an important milestone helping to mobilize political momentum and to build a robust international process around the climate challenge. But at the time, as related to us in a recent presentation byDr. Robert Bindschadler, Emeritus Scientist on Hydrospheric and Biospheric Sciences at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, ice sheet dynamics were not accounted for in these projections.

In the tropics, far away from the polar ice caps, the difference between “accounted for” and “not accounted for” is not merely a margin of error in a report. For the 41 million people living on the 43 island nations that girdle the planet, it is a matter of survival. With this new information, low-lying coral atolls in the Indian and the Pacific Oceans are facing a real and present danger of sovereign extinction. Caribbean islands face inundation with storm surges heightened by more intense hurricanes due to sea temperature rise.

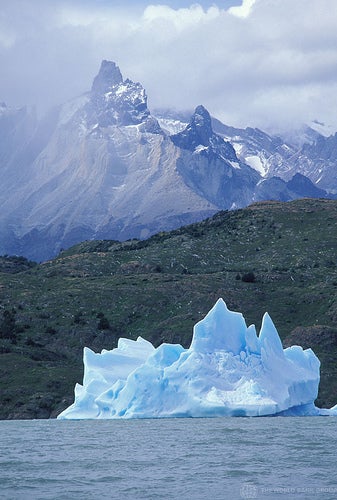

The role of sea temperature rise is key to understanding the impacts on ice sheet dynamics. Warm sea temperatures attack glaciers at their edges in the sea and also open wedges in the ice from below. This causes a further break-up of the ice allowing glacial flows to increase even faster. The result is a more rapid increase in sea level rise than previously predicted. For example, in Jakobshavns Isbrae in Greenland, a glacial terminus that took approximately 60 years to retreat by about 13 kilometers in the early 1900s, retreated the same distance in only five years from 2001. According to AMAP, the melting of Arctic glaciers and ice caps, including Greenland's extensive ice sheet, is projected to help raise global sea levels by up to 1.5 meters by 2100. Hundreds of millions living in low-lying and flood-prone territories in the Americas, Africa and in Asia will suffer, raising the specter of mass migrations and humanitarian crises.

Being amongst the most vulnerable, Island States are not prepared to gamble on the IPCC’s 50:50 chance of serious consequences if atmospheric temperatures rose to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Instead they are calling on the international community to stabilize global temperatures at 1.5 degrees equivalent to 350 parts per million of atmospheric carbon dioxide. But even at 2 degrees, as agreed in Cancun, global commitments and actions on mitigating green house gas emissions are only 60% of what is required to meet this less ambitious target. Having served as a negotiator, I am not entirely convinced that the glacial pace of the negotiations will provide the only solution to fast tracking low-emissions development at the scale needed to avert the climate crisis.

The negotiations remain central, but at the periphery it is vital to scale up actions on the ground. Developing countries are not waiting on the negotiations. They are taking actions today. For example, at $54 billion, the largest investments in renewables are in China. At the World Bank, 88% of developing-country clients are integrating climate change into their national development strategies, up from 15% five years ago. And while they are least responsible for climate change, the islands are playing their part. I applaud the Alliance of Small Island States, for going beyond the negotiations to implement SIDS DOCK, a renewable energy program, with the support of the Danish Government, UNDP and the World Bank.

If we are to harness momentum on the ground, we will need to see more collaboration on policy implementation combined with more innovations in adaptation and mitigation technologies and the financial arrangements to speed up their implementation at scale. For all of us in international climate choir, whether negotiator, implementer or policy maker, this new report is another reminder that the conductor is not our political processes, but the science itself. And right now, we are seriously off beat.

Join the Conversation