When the report Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict was released, UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated, “Preventing violent conflict is a universal concern. It is not only for those in a specific region or income bracket. We are all affected, and we must work together to end this scourge.” However, achieving the worthy goal of preventing violent conflict seems far away. In fact, recent years have experienced an increase in the number of ongoing conflicts.

Why is it so hard to prevent conflict? One reason is because preventing conflict involves predicting the risk of conflict, and prediction sets us up to react to conflict rather than prevent it.

This answer is built on a simple statistic. If a country does not have a recent history of violence, the likelihood of it experiencing the start of a civil war is less than 1 percent. However, countries with a recent history of conflict face more than a 9 percent chance of experiencing another outbreak of civil war. In other words, the risk of conflict is nine times higher in countries that have recently experienced conflict. This means that actors involved in preventing violence have a clear incentive to concentrate resources on cases that involve recent violence. Spending resources on countries that come out of conflict amounts to spending resources on cases with an objectively high risk of future conflict. The prediction of conflict drives us toward late interventions.

Why is this a problem? After all, risk is a lot more concentrated post-conflict. It seems obvious that resources should be spent where they are most needed. In my background note, “How Much Is Prevention Worth?” I use a simple model of the conflict cycle to show that this simple logic contains a significant mistake. Over the long run, prevention money is well spent even if it only achieves small reductions of an already small likelihood of conflict. The reason is that pre-conflict peace is much more stable than post-conflict peace. So, if we learn how to prevent violence through stabilization, we have the ability to change a country’s future. Even a small change in the likelihood that a country will fall into a cycle of repeated violence means we have made a significant impact in that country’s trajectory.\

To illustrate, imagine you are evaluating the fragility of a vase. You could evaluate its characteristics and spend resources analysing the risk that it will break. Or you could wait until the vase falls on the floor—if it breaks, it was fragile. There is no better way to be sure the vase is fragile than to see it break. A country’s fragility is largely the same, as are our responses to it. We typically respond to circumstances that are objectively the riskiest, but in doing so we move away from true prevention. A better path is to treat countries as fragile even when they have not yet experienced conflict.

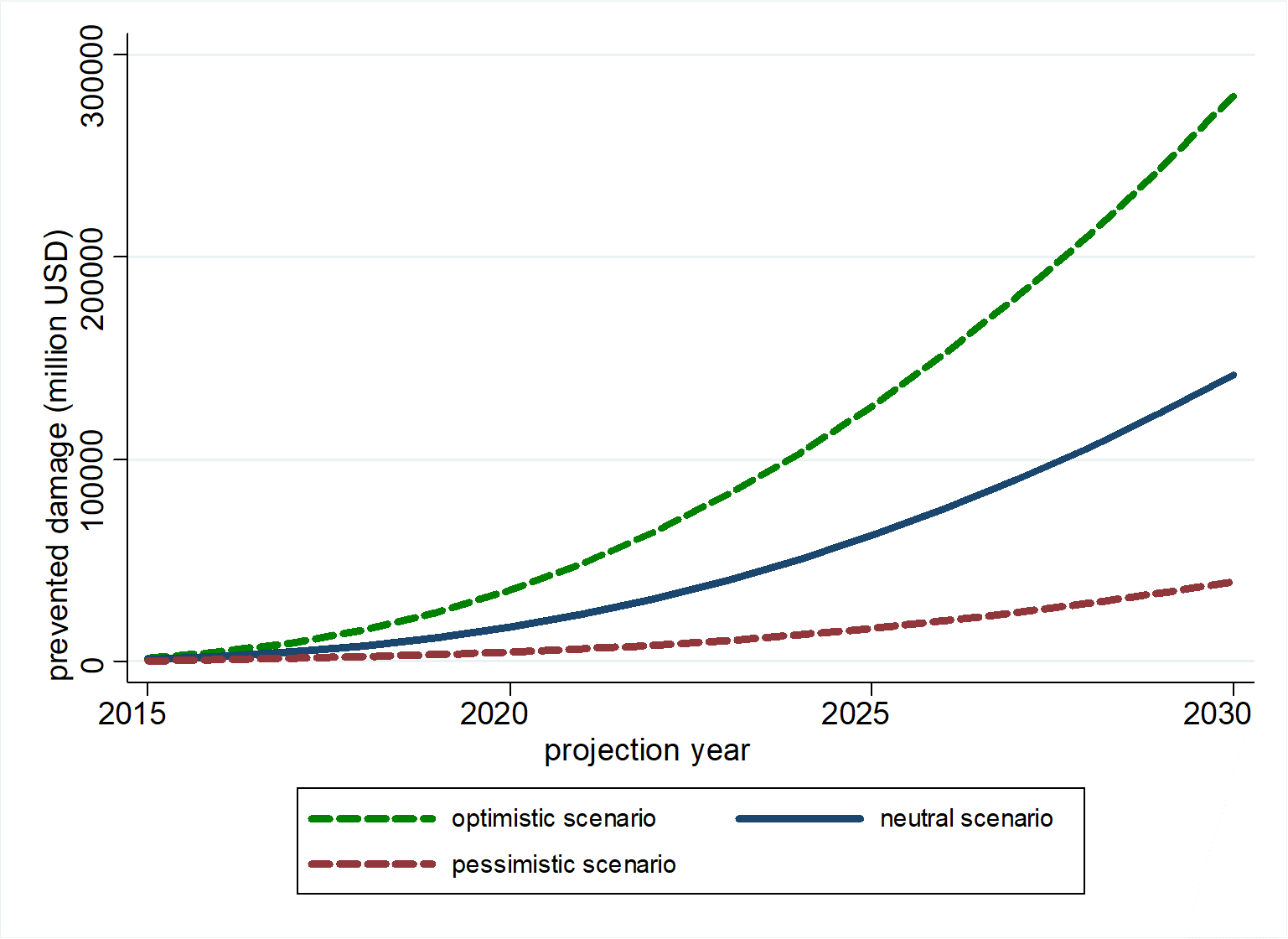

In the report, I use modern prediction methods to spot situations in which conflict might break out, and in which prevention could be practiced before violence occurs—that is, before humanitarian aid, peacekeeping, or peacebuilding become necessary. I then simulate different scenarios of prevention. According to the main scenario, adopting prevention strategies in about five countries each year would prevent about US$34 billion in losses per year, at a cost of US$2.1 billion in the initial years following adoption. In addition, the donor community would save close to US$1.2 billion each year from spending less on aid and peacekeeping. Systematic prevention would also lower the number of refugees by over 1.5 million within 15 years. Over time, costs would fall and benefits would rise, so that after 15 years, prevention benefits in the main scenario reach US$150 billion per year. By that time, prevention would almost pay for itself in the reduced costs for aid and peacekeeping.

But prevention means engaging with countries that are still experiencing peace. To do this, we need to have the courage and foresight to invest resources in cases that display a high degree of uncertainty. This means we need to learn how to spot and address latent conflict. It involves taking the long view and spending more resources on cases that have a less clear, immediate return. It also means garnering the political will and developing the tools to help governments defuse the roots of social conflict—even if these have not yet become violent.

Consider the following figure, which is published in Pathways for Peace. It shows the results of a simulation of three prevention scenarios: (1) an optimistic scenario, in which prevention works most of the time and leads to big gains in growth; (2) a pessimistic scenario, in which prevention works in only one out of four attempts and has a relatively minor impact on growth; and (3) a neutral scenario that lies between these two extremes. As can be clearly seen, the benefits accumulate over time as more and more countries enter peace and as their economic growth accrues. Of course, it is hard to forecast the future in this way, and the scenarios depicted in the figure make this uncertainty clear. But it should also be clear that the gains from true, subtle prevention could be enormous.

Join the Conversation