Global debt concept

Global debt concept

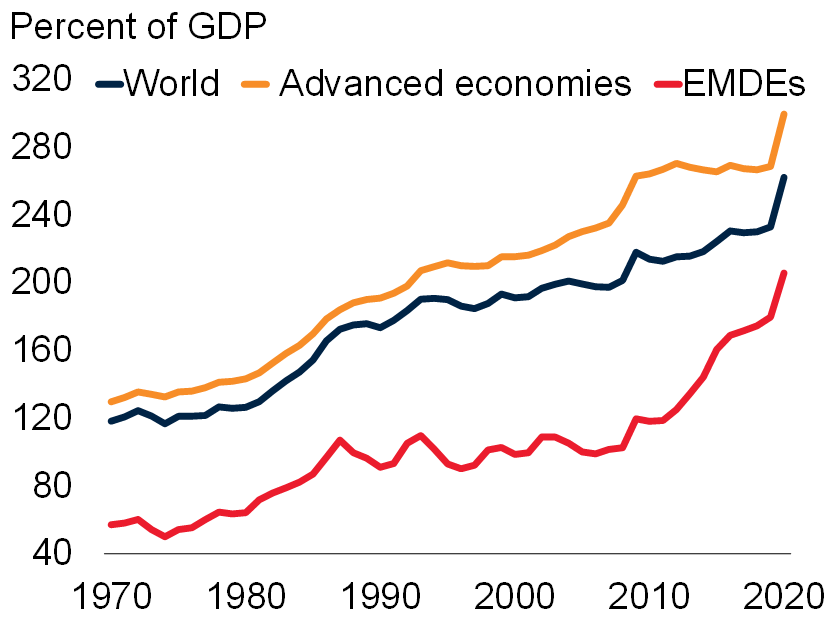

Economies across the globe face a daunting challenge: the highest global debt levels seen in half a century. As The Aftermath of Debt Surges points out, policymakers need to prepare for the possibility of debt distress when financial market conditions turn less benign, particularly in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs).

The pandemic-induced recession of 2020 led to the largest single-year surge in global debt since at least 1970. In addition, this came on the heels of a decade-long global debt wave that was the largest, fastest, and most broad-based in the past five decades. Government, private, domestic, and external debt are all at multi-decade highs across advanced economies and EMDEs. Furthermore, while interest payments in advanced economies have been trending lower in recent years while these have been steadily climbing for EMDEs.

So, how can EMDE policy makers address this record-high debt? History offers some lessons, but no easy solutions. In the past, debt reduction efforts used orthodox policy options (enhancing growth, fiscal consolidation, privatization, and wealth taxation) and heterodox options (inflation, financial repression, debt default and restructuring).

- Higher growth, in excess of interest rates, helped some countries to reduce their debt stocks (relative to GDP). Looking ahead, however, several factors argue for caution in relying on growth alone to lower debt burdens. For example, past episodes of debt reduction through rapid growth typically followed periods in which debt ramped up quickly after one-off shocks such as wars. While the COVID-19 pandemic may be similar in some dimensions, the jump in 2020 followed a steady debt buildup during the previous decade because of persistent spending pressures and revenue weaknesses.

- Fiscal consolidation can produce primary fiscal surpluses to pay off debt through expenditure cuts or revenue increases. The loss of access to financial markets, or the threat of lost access, has sometimes forced countries into severe fiscal consolidation. However, such consolidation typically comes at the cost of lower growth.

- Proceeds from privatization of public assets have also been used to lower government financing requirements or debt. While privatization may yield benefits for some EMDEs, including debt reduction, some of the preconditions needed to realize the full potential of privatizations are not yet in place.

- Wealth taxes have received renewed interest since the global financial crisis, in part stemming from concerns about an unequal distribution of wealth. However, EMDEs face significant implementation challenges in raising revenues through wealth taxes.

- Unexpected inflation erodes real debt burdens if it raises nominal incomes faster than nominal interest rates rise. However, inflation has drawbacks as a debt reduction strategy. For example, inflation is typically accompanied by exchange rate depreciation, raising debt when the share of short-term debt or foreign currency-denominated debt is large. High inflation also risks undermining the hard-won credibility that EMDE central banks have achieved over the past three decades. And if high debt is the result of persistent spending pressures or revenue weakness, a bout of surprise inflation cannot reduce debt in a lasting manner.

- Financial repression, such as capital controls and certain financial sector regulatory measures, are means to depress differentials between real interest rates and growth rates by trapping savings in specific instruments. However, financial repression is a costly way of lowering debt because it discourages more productive uses of savings. In addition, decades of capital account and financial liberalizations have reduced governments’ room to use financial repression to lower debt.

- Default and restructuring are sometimes a country’s only option to deal with debt owed to foreigners, denominated in foreign currency, and adjudicated by foreign courts. While default and debt restructuring may offer immediate debt reduction, they also impose long-term costs. For example, bond holders are typically compensated for default risk by excess returns, especially in countries with a history of serial default. Protracted restructuring negotiations prolong the loss of market access and can weaken balance sheets of financial institutions and undermine financial stability.

- Domestic debt default is different than external debt default and includes forcible conversions, lower coupon rates, unilateral reduction of principal (sometimes with a currency conversion), and suspensions of payments. But governments defaulting on domestic debt are still vulnerable to inflation risk and to interest rate spikes should inflation expectations become unanchored.

Unfortunately, none of the options to deal with debt are attractive or easy. Inflation, financial repression, and debt restructuring can impose heavy economic and social costs. Wealth taxes or reforms to generate higher growth can face difficult technical, practical and political obstacles. The exact mix of available options obviously depends on the specific situation in each country and the type of debt concerned.

As long as debt problems remain more pressing in EMDEs than in advanced economies and there is no easy path to debt reduction, there remains the prospect that the inequality between advanced economies and EMDEs becomes much worse. The difficulties associated with debt reduction also raise many questions about global governance. As the global community is getting ready for the World Bank-IMF Annual Meetings next month, an important question to consider is how advanced economies can better help EMDEs overcome debt challenges.

Figure 1. Total Debt

Sources: Kose et al. (2017, 2020); Mbaye, Moreno-Badia, and Chae (2018).

Note: Includes government and private debt. Data are available until 2020 for up to 191 countries. Nominal GDP weighted averages.

Join the Conversation