A young woman sorts coffee at the Coffee Washing Station at Musasa, Northern Province, Rwanda. Photo: A'Melody Lee / World Bank

A young woman sorts coffee at the Coffee Washing Station at Musasa, Northern Province, Rwanda. Photo: A'Melody Lee / World Bank

The summer of 2007 is notoriously remembered for the turmoil in the subprime mortgage market in the United States that led to the collapse the following year of Lehman Brothers, one of the oldest houses in Wall Street, and ushered in the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. The financial crisis engulfed about a dozen advanced economies (AEs) and pulled down dozens of emerging markets and developing countries (EMDEs) as the global economy slipped into recession. While the press coverage focused on the unfolding financial meltdown of the wealthy economies, a very different type of crisis brewed in parallel, that would have a disproportionally greater impact on EMDEs than in AEs. This was the global food crisis of 2008, the less famous sibling of the financial crisis.

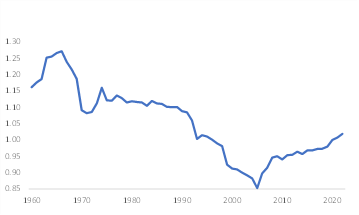

Since the outbreak of the pandemic and the resulting plethora of supply disruptions in early 2020, “global real or relative food prices” (i.e., food prices divided by the consumer price index, or CPI) have been climbing higher once again (Figure 1). This builds on a perilous base. Already in 2020, more than 800 million people were estimated to be suffering from hunger, one hundred million more than the previous year (UNICEF, 2021). The pandemic, a once in a century event, has now been followed by another rare calamity—the first war in Europe since 1945. The latter has led to further price surges in oil, wheat, corn and other international commodities. Early data on March food prices for over 50 countries point to the build-up of price pressures in food over and beyond the marked global rise in inflation rates.

We document global developments in real food prices with an emphasis on comparing the 2008 and the post-2019 price increases and their incidence across the globe. We highlight some of the differences across regions and country income groups. Rising real food prices are an exceptionally regressive shock—both within countries as well as across them . Policy responses to food price pressures are also discussed.

Figure 1. Consumer Prices: Food/All Items, 1960-2022:3

Average all countries

Sources: Authors’ calculations, International Financial Statistics. IMF, Trading Economics, Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge (2021 and updates), and various country sources.

The food crisis of 2008

Global real food prices had been trending lower since their major spike during the OPEC oil shocks of the mid-1970s and hit bottom in 2005 (Figure 1). As the crisis in global financial markets unfolded in 2007, the average increase in real food prices across the 124 countries with available data for that year rose to 2.2 percent, the largest annual increase since 1973. In 2008, the average increase in real food prices for all countries doubled to 4.4 percent and remains the highest on record since at least 1960. The median increase that year for EMDEs was higher still, pushing an estimated 155 million people into extreme poverty (de Hoyos and Medvedev, 2011).

Figure 2 traces the share of countries with an annual real food price increase greater than 4 percent. While the crisis of 2008 stands out with slightly over one-half of countries registering large increases, it is possible that the crisis of 1973 was more acute than it appears. This is because food price data for low- and middle-income countries is far less comprehensive for that episode than over the past four decades.

Figure 2. Share of countries with real food price (food/all items) increases > 4%

All countries, 1960-2022:3

Sources: Authors’ calculations, International Financial Statistics. IMF, Trading Economics, Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge (2021 and updates), and various country sources.

Food prices during the COVID-19 crisis

During 2020, real food price increases averaged 2.2 percent across 180 countries, making it the largest gain since the crisis of 2008 (Figure 3). While price pressures eased somewhat in 2021, the upward march in real food prices continued uninterrupted. Price hikes picked up steam in early 2022, even before the spillovers from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. About 15 percent of all countries have posted increases in real food prices larger than four percent in the first 2-3 months of 2022 . Yet, the scale of the problem remains well below the extremes of the 2008 food crisis--but it is still early days in the aftermath of the war shock.

Figure 3. Average and median annual percent change in food prices: All countries, 1960-2022:3

Sources: Authors’ calculations, International Financial Statistics. IMF, Trading Economics, Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge (2021 and updates), and various country sources.

The post-2019 price increases, as during 2007-2008, were not uniformly distributed across income groups. The rise in relative food prices is regressive for at least two reasons. First, as Figure 4 highlights, once again as in 2008 the overwhelming concentration of large increases in real food prices are in EMDEs. Second, in EMDEs, food accounts for about 30-45 percent of expenditures, or 2-3 times the share in high-income AEs (Table 1), magnifying the impacts of price changes in household budgets.

Table 1. Food share by income group

| Income group |

Food share in expenditure |

|---|---|

| Low-income |

0.42 |

| Middle-low-income |

0.40 |

| Middle-high-income |

0.29 |

| High-income |

0.15 |

Sources: USDA (2017), Nomura (2019), JP Morgan (2022), and various country sources.

Figure 4. Share of advanced economies and EMDEs with real food price (food/all items) increases > 4%

All countries, 2001-2022:3

Sources: Authors’ calculations, International Financial Statistics. IMF, Trading Economics, Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge (2021 and updates), and various country sources.

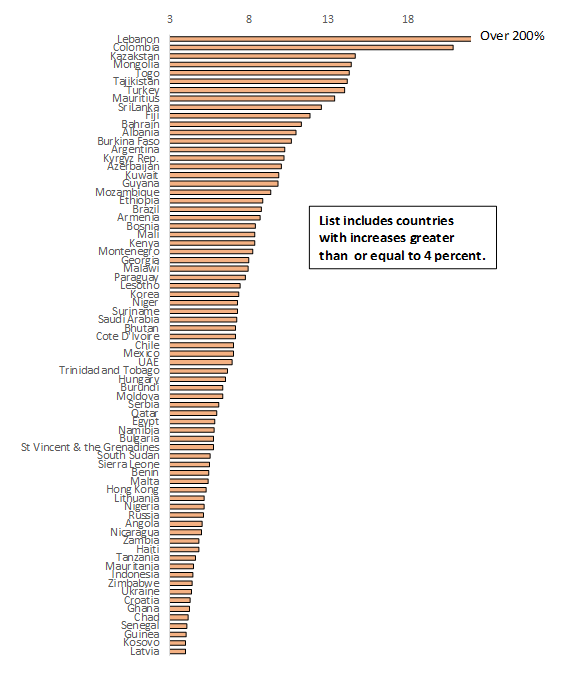

Figure 5, which lists the countries with the largest price increases, speaks to the more granular geographical pattern of the recent price increases. It also provides a snapshot of the cumulative effects since the outbreak of the pandemic. The 2008 food crisis did not erupt in a single year, it was the cumulative effects of two consecutive years of outsized increases in the cost of food. This time, Sub-Saharan Africa and Emerging Europe and Central Asia are the two regions with the most pronounced sustained food price increases to date (about 36 and 26 percent of the 73 countries shown in Figure 5, respectively). They are also among the regions most affected by the Russia-Ukraine war given the structure of their imports (see Kammer et al. 2022 and Artuc et al. 2022).

Figure 5. Change in real food prices since December 2019. (CPI food/CPI all items, percent)

Sources: International Financial Statistics. IMF, Trading Economics, Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge (2021 and updates), and various country sources.

Policy without panic

Surges in food prices have often coincided or been closely followed by all manner of civil unrest and political turmoil, so it is hardly surprising that food price hikes trigger impromptu and often panicky policy responses that have often ended being counterproductive in the short-run and distortionary in the long run . Restrictions on food exports during the Global Food Crisis of 2008, were enforced in nearly a third of all EMDEs and significantly aggravated price pressures (Ha et al. , 2019). During the pandemic, governments have been more circumspect in resorting to such policies. However, since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, a rising number of EMDEs have fallen back on such policies. As in prior instances, the accompanying narrative is that the measures will be temporary, but all too often it is easier to introduce than to remove these policies. It is too early to speculate what their legacy will be.

Another common policy aimed at stabilizing conditions for the most vulnerable low- income groups as their purchasing power erodes are price controls, which is understandable but misguided. Recent work reviewing the efficacy of such policies in a large body of country experiences concludes that price controls “can dampen investment and growth, worsen poverty outcomes, cause countries to incur heavy fiscal burdens, and complicate the effective conduct of monetary policy” (Guenette, 2020). At times of rapidly rising food prices, a less distortionary policy response to support the poorest households is through targeted social protection programs that are both more progressive and, possibly, less damaging to government finances. Yet, the setup of targeted transfers requires more time and government capacity than flat subsidies. Timely action requires a prompt start.

As Figure 5 attests, many EMDEs are already facing a significant cumulative increase in real food prices since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. A food crisis on the scale of 2008 may or may not repeat itself in 2022. But whether it does or it does not, policymakers across the globe would do well to avoid the mistakes of the past. A pre-emptive and rapid response from the international community to address the food price crisis is critical to prevent the worst humanitarian outcomes and lessen the risk of panicky policy responses .

Join the Conversation