Minasa Upa Central Market, Gowa Regency, Indonesia. | © shutterstock.com

Minasa Upa Central Market, Gowa Regency, Indonesia. | © shutterstock.com

Advanced and developing economies in 2022 recorded their highest inflation rates for over a decade (Global Economic Prospects, January 2023). Global inflation soared in 2022, rising above 9 percent. Drivers included supply bottlenecks, the release of post-pandemic pent-up demand, and high commodity prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

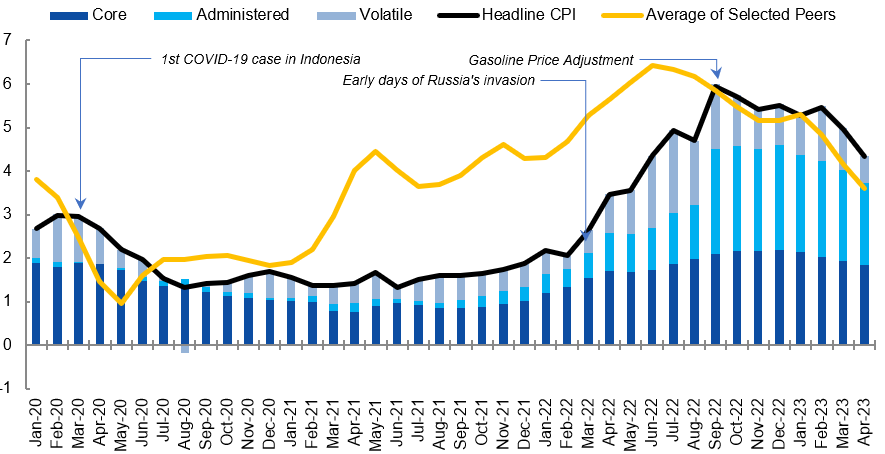

Indonesia’s inflation rate bucked the global trend by peaking at 5-6 percent in the second half of 2022 despite pressures from increasing demand and rising input costs. Unlike its peers, Indonesia’s inflation rate remained broadly flat (Figure 1) and only started to pick up with rising global commodity prices in early 2022.

To contain budget subsidies, the authorities partially removed caps on fuel prices in September 2022, resulting in a 30 percent increase in gasoline prices. This led to the highest inflation level in seven years. However, inflation has since tapered down and by July 2023, it fell below the upper bank of Bank Indonesia's inflation target range of 2-4 percent.

Why was inflation in Indonesia relatively muted compared to peers?

Figure 1: Administered prices contributed largely to inflation since September 2022

(contribution to inflation, percentage points)

Source: BPS, CEIC, World Bank staff calculations.

Note: Selected peers are Brazil, China, Malaysia, Philippines, India, and Thailand. Administered inflation is defined as increase in price of goods and services whose price development is regulated by the government. Volatile inflation is defined as increase in price of goods and services that experience high volatility (i.e., foods).

The study examined the passthrough of producer price inflation to consumer prices as 2022 inflation pressures were mostly due to supply side shock. Despite higher input costs, producers did not fully pass on these costs to consumers. The gap between producer prices and consumer prices widened as input costs increased (Figure 2). This could be attributed to producers' concerns about customers reducing demand when price increased, reduced profit margins and/or lower product quality, and price caps on consumer prices.

Figure 2: Inflation gap between producer and consumer widens as energy price increases.

(inflation gap, percentage points; global oil price, percent yoy change (RHS))

Source: BPS, CEIC, World Bank staff calculations.

Note: Positive inflation gap reflects that PPI inflation is higher than CPI inflation, while a negative gap reflects the converse. Gasoline Price Adjustment period shows time where there’s an increase of gasoline price. We refer to Premium or Pertalite Fuel as these are the most consumed fuels.

Using an impulse response function, we found that passthrough from producer to consumer prices historically has been negligible and only begins to rise five quarters after the initial shock (Figure 3). Sectors with government price interventions had weaker passthrough compared to sectors with no intervention (Figure 4). For example, rising input costs in transportation, agriculture, and electricity sectors which often are subject to price caps, were passed on at a lower rate compared to the hospitality sector. Passthrough in the electricity sector is small as tariff rate is rigid and has not been adjusted for several years.

The presence of subsidies, price interventions, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in highly regulated sectors played a role in softening the impact of external shocks on household consumption. Indonesia has among the highest levels of support through public transfers to producers in East Asia and Pacific (EAP) countries (Figure 5).

These findings raise important questions about the appropriate policy mix for managing inflation during a supply shock when demand in the economy is strong. Price interventions, while protecting consumers from price shocks in the short term, can have negative long-term economic consequences. They can distort markets, discourage competition, and hinder investment and growth.

Price interventions are commonly used in developing economies to protect consumers from price shocks. However, it has harmful economic consequences over the longer-term. It can dampen investment and growth as it distorts markets and discourages competition. Other consequences include poor policy targeting (i.e., administrative prices tend to go to rich households and large firms more than poor households and MSMEs) and lower fiscal space for other priority spendings.

In conclusion, our analysis suggests that Indonesia’s relatively low inflation primarily stems from the low transmission of producer price inflation to consumers. This could partially be attributed to price caps for certain goods and services. Whilst price interventions may help contain near-term inflation, they may also pose challenges for the monetary policy response. Over the longer-term, sustained price interventions can hinder allocative efficiency.

This blog post is based on: Indonesia Economic Prospects, December 2022 Edition.

Join the Conversation