The following post is a part of a series that discusses 'managing risk for development,' the theme of the World Bank’s upcoming World Development Report 2014.

One thing financial markets are good at is innovating and creating new instruments that meet the ever-evolving needs of investors and economic agents managing their risks (such as national or subnational governments). In the mid-1990s, after hurricane Andrew and the Northridge earthquake in the United States, it became increasingly clear that some risks were too big to insure with existing instruments. This matters most to governments and insurers who have to pick up the pieces after a natural disaster as the frequency and cost of natural hazards have been increasing over the past few decades.

In the aftermath of a natural disaster, governments have to shift budgetary resources away from new investments for development to relief and reconstruction efforts. For insurance companies, catastrophic events can put pressure on their financial viability. One way to relieve the pressure is to transfer such risks to capital markets. That is how catastrophe bonds (cat-bonds) were born, as financial instruments to further disperse the risk of natural disasters more broadly and use the risk-taking capacity of institutional investors worldwide.

The way cat bonds work is straightforward. For example, a government looking to insure itself against financial risks from natural disasters would issue a coupon-paying bond with coverage of a certain set of disasters in a particular area. Should a covered event occur, the government would stop paying coupons (insurance premium) and retain the principal of the bond, originally placed in a trust fund, to help financing the expenses it faces in the aftermath of the disaster.

Cat bonds also rely on parametric insurance: the cat bond payout is triggered by certain parameters reaching predefined values or triggers (magnitude of an earthquake, wind speed on the ground in the case of a hurricane) and the insurance payout is derived from these parameters.

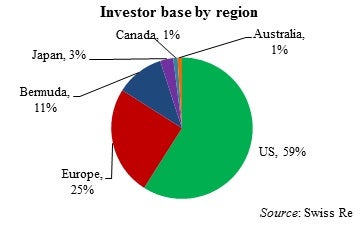

Notably, the only country that has so far issued catastrophe bonds is Mexico. While they are simple instruments to understand, they are tremendously complex to price. Emerging countries usually lack the knowledge, information and capacity to deal with these kinds of instruments and do not have the experience in dealing with the different actors that need to be involved (reinsurance companies and global investment banks to underwrite the securities, law firms to advise the client, modeling firms and so on). Therefore, they are typically issued and bought by insurance and reinsurance companies in developed countries, where financial markets are more advanced.  However, developing countries are more prone and vulnerable to disasters given their greater exposure, weak infrastructure, and limited access to risk management tools and markets. Often times, lacking resources, capacity and developed financial markets offer very little means for them to prepare and deal with disasters, providing a rationale for the international community to step in.

However, developing countries are more prone and vulnerable to disasters given their greater exposure, weak infrastructure, and limited access to risk management tools and markets. Often times, lacking resources, capacity and developed financial markets offer very little means for them to prepare and deal with disasters, providing a rationale for the international community to step in.

The international community indeed stepped in. In 2009, the World Bank Group launched the MultiCat program, providing governments with access to international capital markets to insure themselves against the risk of natural disasters on affordable terms by issuing catastrophe bonds. The program has created “Multi-peril cat bonds” by allowing a country to pool different types of disaster risks for multiple regions. This higher level of diversification, due to the bundling of uncorrelated risks, leads to a lower insurance cost and a broader coverage for the issuers.

Through the MultiCat program and in collaboration with its clients, the World Bank also disseminates and shares knowledge, provides technical assistance and a common framework and builds capacity in designing such instruments against catastrophic events. The World Bank also serves as an actor to arrange bond issuances, boosting investor’s confidence in the process. It uses its extensive network to select the needed agents and help coordinate the relevant parties. For example, having models that can accurately forecast the probability of a disaster in a specific area is particularly important for the pricing of the bond, but these models can become tremendously complex—too complex for emerging market too handle alone at first. This is where the International Community, with its network and financing capabilities can help.

Partnered with the MultiCat program, Mexico issued a multi-peril cat bond in October 2009 and again in 2012, shifting its disaster strategy toward a preemptive approach to reduce its budgetary risks. This experience could provide a good example for other countries exposed to natural hazards. The MultiCat program empowers the country, allowing it to choose the coverage of the instrument based on its risk aversion and the cost and return relationship. Information, knowledge and capacity transmitted by the international community are key in these decisions, to ensure cost effectiveness and minimize the risk of missing areas for coverage. The availability and favorable experience with these global insurance instruments could provide effective ways for countries to insure against the financial effects of the risks that exceed their capacity, as part of a holistic risk management strategy.

Join the Conversation