In the 1970s and 1980s, Nepal was faced with large-scale deforestation due to land clearing, and forest degradation caused by fuelwood collection and uncontrolled grazing by villagers who were the de facto controllers of forests. Centralized management and control was clearly not working.

Rather than tightening control, the Government of Nepal recognized that the downward spiral was related to nationalization of forests in 1957. Nationalization disrupted traditional local management structures and removed local incentives for conservation and investment; the government lacked resources to fully manage and invest in the forests, which were now under its control.

Instead of allowing forests to continue to deteriorate, the country took to heart emerging evidence on the importance of local-level collective action for natural resource management. In particular, the government recognized that local-level collective action may be an important foundation on which forest policy could be built, and began a process of forest re-devolution.

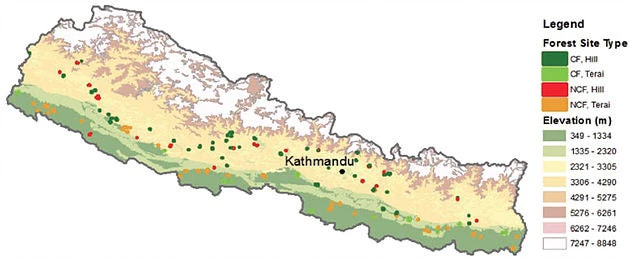

Figure 1: Sample of Forests and Forest User Group Members

The Forest Act of 1993 – which has been revised thereafter – was the result of this process and provided a clear legal basis for the government to ‘hand over’ national forests to community forest user groups. The forest user groups are recognized as institutions that can acquire, possess, transfer or manage property. They can also sell and distribute forest products according to operational plans approved by government officials.

The Nepal Community Forestry Programme now includes about 19,000 Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) and over 2.4 million households – this is about 35 percent of Nepal’s population – managing almost two million hectares. Three-quarters of groups are in the hills and as of 2015 almost 80 percent of hill households were members of CFUGs. Nepal’s REDD+ activities are largely focused on the CFUGs, and it is therefore important to understand linkages between the Program and a variety of outcomes, including carbon sequestration.

Forest devolution sounds good, but it would not be the first potentially positive policy innovation that did not pan out. I joined a number of co-investigators from around the world – including ForestAction Nepal headquartered in Lalitpur, Nepal – to collect forest data from 620 forest plots based on a nationally representative random sample of 65 CFUGs and 65 forests outside the Programme. Supported by the World Bank, our aim was to understand the impact of the Nepal Community Forestry Programme by comparing it with forests that are not governed by CFUGs and are officially government-controlled. The areas we sampled were heavily used by local people. We also surveyed 1300 households; one half CFUG members and the other half non-members.

Figure 2: A degraded open access forest in Nepal

We found that the Nepal Community Forestry Programme offers a variety of positive outcomes, but not surprisingly it is not a cure-all. Based on household data, we conclude that those who are members of CFUGs see their groups as more fair and equitable with regard to benefit sharing than those outside the Program. Those living in poverty, members of indigenous groups, Dalit respondents and members of women-headed households reported that their groups are more fair when they are CFUG members than when their groups are outside the Program. This is not to say that traditionally disadvantaged groups feel the same as non-disadvantaged groups, but they are clearly happier with their forest user groups when they belong to a CFUG.

A concern about devolution is that local groups may focus on a relatively few commercial tree species and suppress species that cannot be commercialized. Such an approach could reduce tree biodiversity. Alternatively, securing local-level property rights through devolution could offer members the opportunity to allow forests to recover without worrying that nonmembers will reap the rewards of their investments.

We find strong evidence that on average, the latter effect dominates and CFUGs improve tree biodiversity. Measured as effective number of species – regardless of forest type – forests that are governed by CFUGs have more tree biodiversity than government forests. In most cases results are also highly significant statistically.

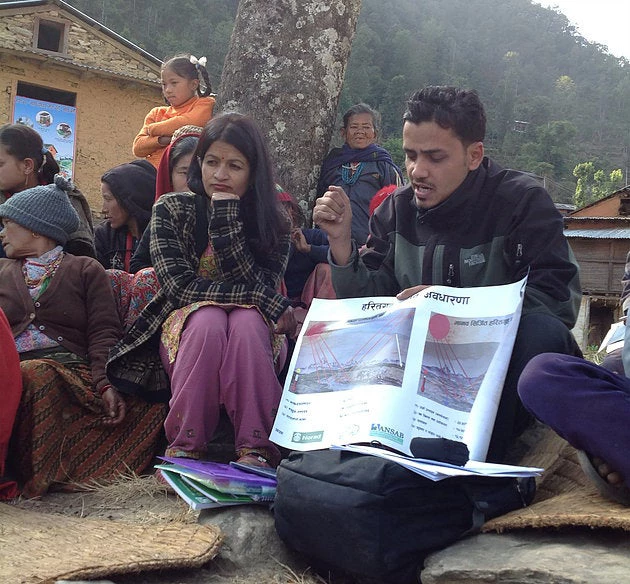

Figure 3: A meeting in progress of a community forest user group

We find strong evidence that on average, the latter effect dominates and CFUGs improve tree biodiversity. Measured as effective number of species – regardless of forest type – forests that are governed by CFUGs have more tree biodiversity than government forests. In most cases results are also highly significant statistically.

However, though CFUGs do no worse than government-controlled forests, we find they do not contain more carbon than government forests. This does not mean that they store less carbon, they have roughly the same amount of carbon as forests outside the Program. Digging deeper, we found that it is not really being part of the Nepal Community Forestry Program that matters to people, but collective action behaviors themselves. Collective action shows large, positive, and statistically significant carbon effects compared to communities exhibiting no evidence of forest collective action. Comparing user groups that show evidence of collective action with those lacking such behaviors (i.e. uncontrolled, free or ‘open access’ forests), we find strong effects of collective action.

Indeed, open access forests may have little more than one-third of the carbon of forests that are governed by groups showing evidence of collective action. When it comes to carbon storage in Nepal’s forests, we therefore conclude it is collective action, including by CFUGs, that improves outcomes. However, the Nepal Community Forestry Programme does not appear to offer a unique collective action path to increasing carbon storage.

This blog was originally posted at UN-REDD.

Join the Conversation