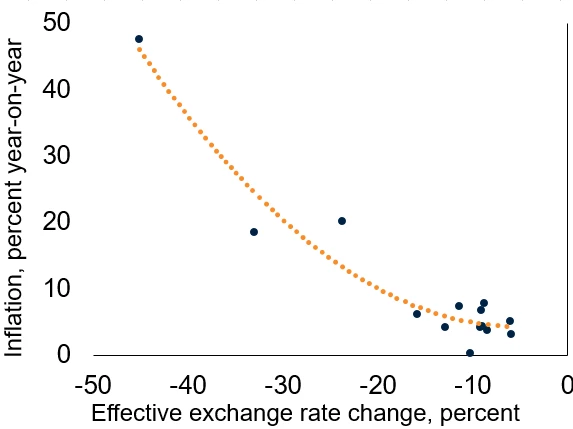

Episodes of financial market turbulence in 2018 illustrated, once again, that emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) continue to face the risk of destabilizing exchange rate depreciations. In particular, inflation rose sharply in countries where currency pressures were most pronounced (Figure A). These stress episodes often compelled central banks to tighten policy to lessen currency pressures and fend off inflationary pressures despite slowing growth.

Inflation rose sharply in countries where currency pressures were most pronounced in 2018.

Figure A: Currency depreciations and inflation in EMDEs in 2018

Source: Haver Analytics, World Bank.

Note: EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies.

The horizontal axis shows cumulative change in the nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) of

more than 5 percent over the period January to December 2018. Vertical axis shows consumer price

inflation in December 2018. Dotted line shows second order polynomial trend. Sample includes 28 EMDEs.

To design appropriate policies, it is important that central banks are able to quantify accurately the exchange rate pass-through to inflation. However, new evidence presented in a special focus chapter of the June 2019 Global Economic Prospects suggests that this pass-through can vary considerably across countries and over time. Three fundamental factors help to account for the wide range of pass-through estimates: the magnitude of the depreciation, the nature of the shock triggering the currency movement, and country characteristics.

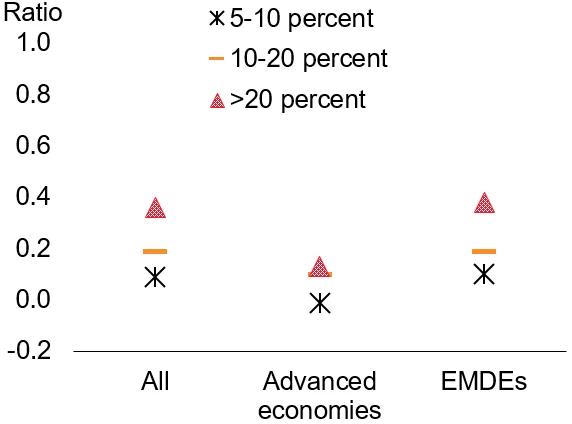

Larger depreciations are associated with stronger pass-throughs. An event study of past depreciation episodes suggests that the pass-through can more than double when the effective exchange rate drops by more than 20 percent in a given quarter, illustrating the presence of non-linear effects (Figure B). This suggests that adopting flexible exchange rate regimes could contribute to lower the exchange rate pass-through, if it helps reduce the likelihood of large depreciations. For countries where pegged or managed exchange rates remain appropriate, allowing for a greater role of currency market discovery and avoiding sharp devaluations from prolonged periods of currency overvaluation are important steps.

Large currency depreciations affect disproportionately domestic inflation.

Figure B: Pass-through from different depreciation episodes, 1998-2017

Source: World Bank.

Note: Depreciations are defined as negative quarterly changes in the nominal effective exchange

rate. The sample comprises 34 advanced economies and 138 EMDEs. Pass-throughs are

defined as the change in consumer prices after one quarter divided by the depreciation of the nominal

effective exchange rate. The markers refer to the median pass-through.

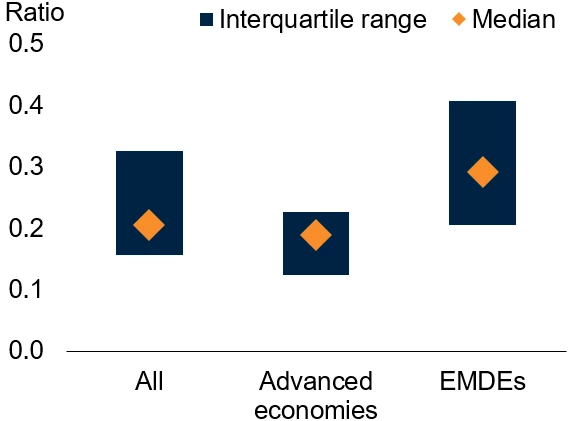

Different shocks can move exchange rates as well as inflation through different channels and, therefore, can be associated with widely different pass-throughs. The pass-through tends to be largest when currency movements are triggered by unexpected monetary policy action, particularly in EMDEs (Figure C).

Monetary policy shocks are associated with a larger pass-through than other types of shocks.

Figure C: Pass-throughs: Monetary policy shocks

Source: World Bank.

Note: Pass-throughs are defined as the ratio of the one-year cumulative impulse reponse of

consumer price inflation to the one-year cumulative impulse response of the exchange rate change

estimated from factor-augmented vector autoregression models for 29 advanced economies and 26

EMDEs over 1998-2017. A positive pass-through means that a currency depreciation is associated

with higher inflation. Bars show the interquartile range and markers represent the median across countries.

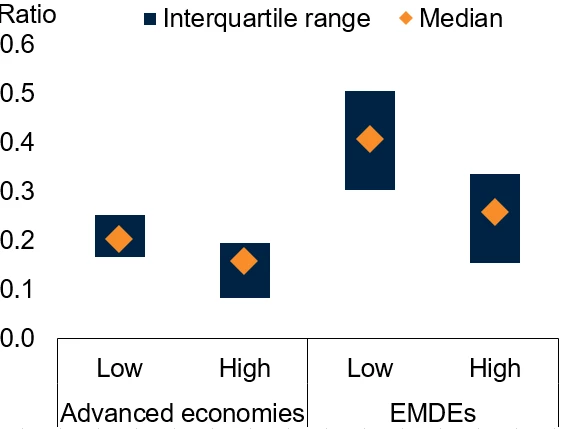

However, this pass-through from monetary policy shocks is significantly smaller when central banks have a credible track record in stabilizing inflation and are more independent from fiscal authorities. In fact, a two standard deviation improvement in the central bank independence index is estimated to reduce the pass-through ratio associated with monetary policy shocks by half (Figure D). A credible commitment to maintaining low and stable inflation remains the most powerful way for central banks to limit the pass-through.

Central bank’s independence helps reduce the exchange rate pass-through.

Figure D: Central bank independence and pass-through from monetary policy shocks

Pass-throughs are defined as the ratio between the one-year cumulative impulse response of consumer price inflation and the one-year cumulative impulse response of the exchange rate change estimated from factor-augmented vector autoregression models. A positive pass-through means that a currency depreciation is associated with higher inflation. Bars show the interquartile range and markers represent the median across countries. Sample includes 29 advanced economies and 26 EMDEs over 1998-2017. Low and high central bank independence are defined as below or above the sample average. Central bank independence is based on the central bank transparency and independence index by Dincer and Eichengreen (2014).

The impact of currency movements on inflation is also estimated to be smaller in countries with explicit inflation targets and with more flexible exchange rate regimes. This implies that countries with such characteristics can better absorb external shocks through currency adjustments without threatening price stability.

Join the Conversation