One widely-accepted political economy research finding is that informed citizens receive greater benefits from

The Benin context differs in three ways. First, the policy is not the distribution of cash, but of health benefits. Households’ access to information then influences not only their knowledge of government programs to distribute such benefits, but also the value they place on them.

Second, the political context also differs. In younger democracies, like Benin’s, citizens are more likely to confront additional obstacles, besides a lack of information, in their efforts to extract promised benefits from government.

Finally, the administrative context is weaker. Local officials therefore have more discretion to implement policies as they wish, including selling health benefits that are supposed to be freely distributed under official policy.

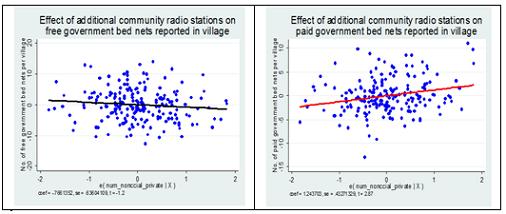

Media markets in Benin allow the effects of these contextual differences to be rigorously examined. Many community radio stations are spread across the country, broadcasting more health and education programming than all other stations. Prior research predicts households with better community radio access would receive more free bed nets from government. Instead, among 4,200 households across 210 villages in northern Benin, these households reported fewer free bed nets and more paid bed nets! Radio access increased households’ willingness to pay for anti-malarial bed nets. It did not improve their access to free bed nets (see figures).

Click here to see a larger version.

What happened? Weak administrative controls allowed officials to exercise pricing discretion, but households with greater access to community radio were not able to persuade them to use this discretion to distribute the nets for free. Nor did they persuade officials to increase the total supply of bed nets in their district. Hence, radio had no effect on the total number of bed nets reported by households.

These results are inconsistent with previous research, so one might be worried that they are driven by idiosyncracies in the radio programming or among the listeners. However, the data inform these questions. Not only do community radios broadcast more health and education programming, households with more access are also more familiar with proper health practices. Both are consistent with the causal channels through which we expect radio exposure to affect access to government programs.

Tritely summarized, then, “context matters.” First, policies interact. In the case of bed nets in Benin, donors and government used both pricing and communications strategies to encourage households to acquire bed nets. More, though, is evidently not always merrier: the communication strategy encouraged local officials to deviate from free distribution.

Second, the effects of removing one “political market imperfection” (lack of information), depend on the presence of others. Uninformed citizens are less likely to see their interests represented by government. However, so also are unorganized citizens: any single aggrieved citizen, even perfectly informed, has little political weight. In countries where government failure is a consequence of weak citizen organization– for example, where political parties are ephemeral and not organized to support the collective interests of party members – information about a policy’s existence is unlikely to trigger more responsive government.

Third, all contexts matter for how we interpret impact evaluations. In an administratively strong country, households with more media access might have reported more, not fewer, free bed nets. Similarly, if policy had required bed nets to be sold rather than distributed for free, these households might have reported owning significantly more bed nets.

These conclusions remind us not to forget about the rest of the social science toolbox when interpreting impact evaluations. In asking whether results from India or Benin are more applicable to an information intervention in some third country, the toolbox is a reminder of principal-agent problems in the delivery of public services – and explains the circumstances under which these are more or less severe. It reveals the multiple conditions that influence whether governments are accountable to citizens. And it alerts us to the potential interactions between the policy whose impact we care about and other policies that happen to be in place.

Despite all of these cautionary messages, this research is encouraging. It may point to the limitations of radio as a device to promote government accountability, but it also shows a large effect of community radio on household demand for a critical health input; anti-malarial bed nets. Even in difficult administrative settings, therefore, community radio health programming can make a significant contribution to our efforts to eradicate malaria.

Join the Conversation