Liberia SME

Liberia SME

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a critical role in the overall growth and development of economies around the globe, and especially in the developing world. SMEs account for an overwhelming majority of new formal sector jobs created in the developing world (Ayyagari et al. 2014). By increasing employment, by contributing to social stability and by enhancing entrepreneurship, SME development is vital in driving inclusive growth. Like other firms, SMEs face several obstacles that limit their growth. Firm-level surveys such as World Bank Enterprise Surveys suggest that one of the biggest, if not the biggest, problems that SMEs face in the developing world is the lack of proper access to finance. Thus, it is no surprise that a voluminous literature has developed identifying factors that constrain SMEs financially. Some of these factors are specific to SMEs while others are common among both SMEs and large firms. Inadequate credit supply in the country, low profitability of SMEs, lack of adequate collateral and credit history, lack of proper enforcement or laws related to loan recovery, asymmetric information about firms’ future profit stream between borrowers and potential lenders are some of the factors that contribute to SMEs’ credit constraints (Blackburn & Sarmah, 2006, Fungáčová et al., 2015; Ullah, 2020, Wellalage et al., 2020).

A recent addition to the list of factors that impact firms’ financial constraint is corruption. We narrow our discussion here to this factor. By corruption, we mean bureaucratic corruption which arises when firms pay bribes to acquire necessary public services such as obtaining licenses or permits to operate, electricity connection, etc. The other type of corruption that arises when firms bribe bank officials to alter loan outcome is not discussed here.

Most economists concur that corruption is detrimental to firms’ growth and overall economic development. It acts as a tax on the private sector, increases uncertainty about future stream of income, and blunts competitive forces by rewarding better connected firms rather than those that are more efficient. However, some argue that the opposite is true. That is, by “greasing” the wheels of an otherwise slow and unresponsive bureaucracy, corruption can contribute to development and growth of the economies (Dreher & Gassebner, 2013; Lui, 1985). Corruption can affect SMEs’ access to finance in several ways. It can lower firm profits and therefore credit worthiness; it can increase credit demand as extra funds are needed to pay bribes; it creates uncertainty about the firm’s future profits since “returns” to bribes paid are inherently unpredictable; it exacerbates the asymmetric information problem between firms and banks about firms’ future profit stream as corruption is a secretive activity; it reduces industry efficiency by blunting the natural competitive forces. However, much like the broader effects of corruption on the economies, corruption can “grease” the wheels of the bureaucracy and improve firm performance. If this happens, corruption may make it easier for firms to borrow money. Thus, the impact of corruption on SMEs’ access to finance is essentially an empirical issue.

A recent study by Amin and Motta is an attempt in this direction. This study uses firm-level survey data (Enterprise Surveys) for SMEs in 114 developing countries collected by the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys team to estimate the impact of higher corruption on SMEs’ access to finance. A major advantage of this study is that it uses data on the actual experience of firms with bribe payments rather than the opinions of “experts” which may suffer from a perception bias. Exploiting the richness of the ES data, the authors deploy two different measures of “petty” corruption and a measure of overall corruption. Petty corruption is defined as corruption that arises when firms conduct the following transactions: obtaining electricity connection, water connection, construction permit, import license, operating license, as well as paying taxes. The measure of overall corruption is based on firms’ reports about the amounts of bribes that firms typically pay to public officials to “get things done” as a percentage of their annual sales. Another advantage of the study is that it uses a comprehensive measure of financial constraint based on whether the firm applied for a loan or not in the last year, reasons for not applying if it did not, and the outcome of loan application if the firm applied for a loan.

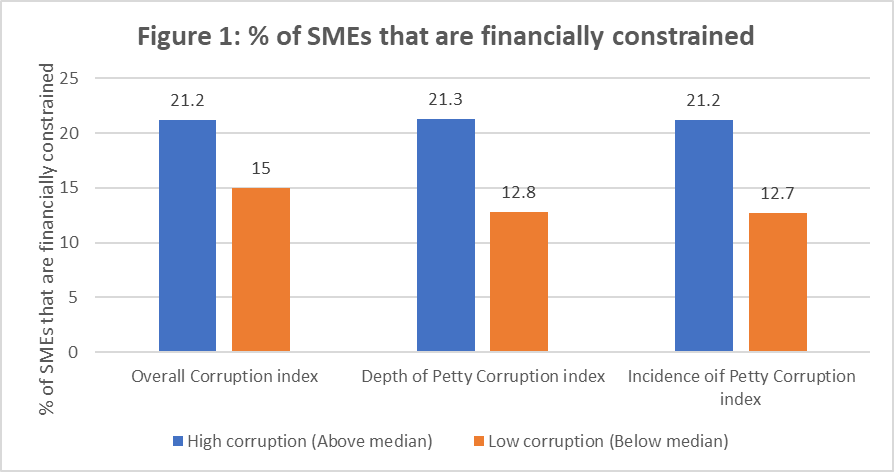

So, what are the results of this study? The study confirms that corruption hurts SMEs’ access to finance. An increase in corruption from its smallest to highest value increases the likelihood of an SME being financially constrained from 6.9 to 10.9 percentage points. This is the most conservative estimate found in the study. Yet, it is a large effect since only 18.2 percent of the private sector firms are financially constrained. Figure 1 shows the corruption-finance relationship using below vs. above median values of the corruption measures used.

Perhaps a more interesting finding of the study is that the corruption-finance relationship is far from uniform. It varies depending on country and firm characteristics. The study discerned two broad sets of heterogeneities. First, the adverse effect of corruption on access to finance is much less severe in countries where financial institutions to protect the rights of borrowers and lenders are stronger, laws provide for better credit information, and credit bureaus exist. The paper argues that these heterogeneities derive from the specific ways in which corruption impacts access to finance. Thus, they help to raise confidence against endogeneity concerns about the main results. The second type of heterogeneity is that corruption is more harmful to firms that, absent corruption, are known to enjoy better access to finance. These are firms that are relatively larger, have all male owners versus at least some female owners, and are better performing firms.

To conclude, there are several important reasons to seriously consider about the impact of corruption on SMEs’ access to finance. First, it highlights another potential channel through which corruption may affect the productivity and growth of SMEs. Second, by failing to acknowledge the adverse effects of corruption on SMEs’ access to finance, previous studies are likely to have underestimated the adverse effects of corruption on the private sector. Third, the corruption-finance link points to the possibility that other elements of the business environment such as stringent business regulations - that also act as a tax on businesses - may affect SMEs’ access to finance. These are exciting avenues for future research.

Source: Based on Enterprise Surveys, World Bank data for 114 countries.

Note: Overall corruption is measured by the percentage of firms that report that firms like itself pay bribes to “get things done”.

Incidence of petty corruption equals the percentage of firms that report paying bribes in conducting one or more of the following transactions: obtaining electricity connection, water connection, construction permit, import license, operating license, as well as paying taxes.

Depth of petty corruption equals the percentage of transactions for which an average firm pays bribes. The transactions covered are as follows: obtaining electricity connection, water connection, construction permit, import license, operating license, as well as paying taxes.

Join the Conversation