Village in Mali, one of FCV countries.

Village in Mali, one of FCV countries.

Over 1.5 billion people worldwide live in areas plagued by violence and conflict. In fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS), gender issues warrant particular attention given the varying needs, coping mechanisms, and obstacles faced by women. Women and girls bear disproportionate impacts from crises and conflicts. However, worldwide, lax enforcement of laws deprives women of their rights (blog).

In 2021, Women, Business and the Law (WBL) began collecting data on measures and processes to support the implementation of laws in 55 economies. The pilot data on legal and supportive frameworks includes seventeen economies that are classified as FCS according to the World Bank. Across the eight indicators covered in the pilot data, in FCS economies, women have about 70 percent of the legal rights of men. In practice, however, women only benefit from supporting frameworks for about 40 percent of these rights (figure 1).

The implementation gap is wider in fragile states, due to a multitude of inherent challenges, such as limited resources, weak governance structures, and ongoing conflicts or instability. Additionally, institutional capacities may be underdeveloped, impeding the proper implementation and monitoring of measures aimed at addressing gender issues. Yet, the effective enforcement of laws becomes a linchpin for stability and development, offering a pathway towards resilience and prosperity for all members of society, especially women.

Women’s property rights and protections from gender-based violence are particularly weak in FCS contexts. To gain a better understanding of the implementation gaps in both areas, Women, Business and the Law’s briefs (see here and here) examine how FCS countries have been working to overcome this divide, as well as good practices to create a safer and more equitable environment for women in such contexts.

The challenges associated with effective implementation of the law become particularly apparent when examining the supportive frameworks established for Assets. Despite laws that may appear to protect women’s rights to property, this is not the case in practice. Among all indicators, the Assets indicator exhibits the largest implementation gap (more than 50 points difference) in FCS contexts (figure 2).

Such measures include programs that support joint titling between spouses, or the enforcement of equal inheritance rights, as women may be forced by male relatives or their communities to waive their rights. Land ownership holds immense significance for both men and women, often serving as a primary form of collateral and a gateway to financial security. Yet women continue to face barriers in accessing and owning land, a disparity exacerbated by lower rates of land ownership and exclusion from land titling processes. As a result, women are often sidelined when it comes to accessing vital financial resources—a cycle of disadvantage that perpetuates economic inequality.

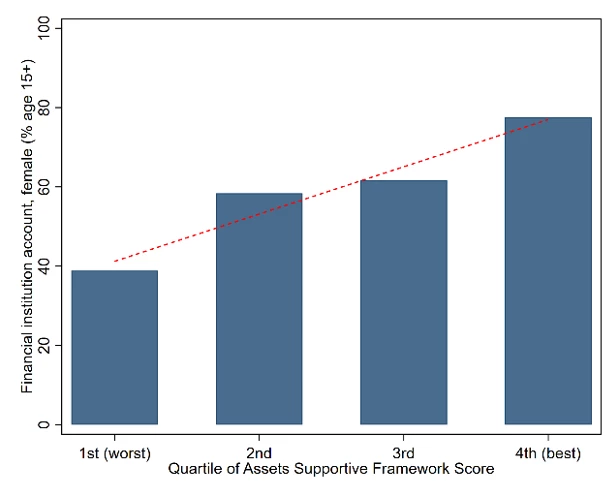

While weak property rights can create obstacles for women to enter contracts and access finance (Perrin and Hyland 2023), economies with a better supportive framework to implement women’s legal rights are associated with higher levels of financial inclusion (figure 3). In the top quartile, where strong supportive frameworks are mostly in place for Assets, almost 80 percent of women have financial accounts, compared to less than 40 percent in economies with lower supportive framework scores.

Figure 3: Better Supportive Frameworks are correlated with higher levels of financial inclusion.

Analysis of the pilot data on violence against women revealed glaring gaps in the legal and supportive frameworks currently in place to protect women from violence both in FCS and non-FCS economies, and between those frameworks. While many FCS and non-FCS countries have legal frameworks on domestic violence, supportive frameworks lag. While 71 percent of FCS economies have legislation on domestic violence (compared to 92 percent of non-FCS), only 12 percent have supportive frameworks in place (versus 26 percent of non-FCS) (figure 4). Measures taken into account among supportive frameworks include legal mandates and the actual provision of services for survivors of domestic violence, such as medical and psychological support, legal aid, and livelihood support, which should also be in place and operational.

Regarding sexual harassment in employment, legal frameworks focused on the prohibition of sexual harassment in employment, as well as criminal penalties and civil remedies. Supportive frameworks included entities responsible for the adoption of anti-harassment policies and measures by employers, as well as special procedures for sexual harassment cases. A similar pattern to the domestic violence one was observed, and there was an even wider gap between FCS and non-FCS economies––ninety-seven percent of non-FCS economies have legislation in this area, compared to 71 percent of FCS economies. The gap for supportive frameworks is even wider, where 58 percent of non-FCS economies have such measures versus only 12 percent of FCS economies (figure 5).

Interestingly, fragile countries have more comprehensive legal and supportive frameworks in place than conflict-affected countries. This may indicate that while institutional capacity is reduced or even nonexistent in both sets of countries, the spillovers from conflict may be much more severe due to the active armed violence, thus minimizing countries’ legislative and institutional capacity. It is therefore critical that policy makers and the international community take action to address this complex and multifaceted issue with a comprehensive and coordinated response, as well as consider the unique attributes of and differences between fragile and conflict-affected countries.

Secure access to land ownership not only empowers individuals, especially women, to safeguard themselves and their families from violence and exploitation but also fosters economic independence and social stability. Conversely, insecure land rights can deepen vulnerabilities, fueling displacement, conflict, and an increased susceptibility to gender-based violence.

Establishing supportive frameworks to ensure the consistent and transparent enforcement of laws is crucial for fostering social cohesion and mitigating conflicts. When laws are translated into practice, protecting the rights of all citizens, including women, they not only reduce grievances but also minimize the potential for social tensions that could escalate into violence or community destabilization. By prioritizing the equitable application of laws, societies can build a foundation of security and inclusivity, paving the way for sustainable peace and development.

Support for the work was provided by the World Bank’s State and Peacebuilding Fund (SPF). The data shared in this blog is part of the pilot “Measuring the law in practice” dataset, and was collected between October 2, 2021, and October 1, 2022. The newest Women, Business and the Law 2024 report provides a better understanding of the status of laws and policies worldwide. By measuring legal frameworks, supportive frameworks, and expert opinions on the status of women’s rights, it presents a new approach to measuring the implementation gap between laws (de jure) and how they function in practice (de facto). The new dataset also broadens its thematic scope by introducing two new indicators—Safety and Childcare—and revising existing indicators.

Join the Conversation