A chemical factory emitting smoke in the middle of a green rice field on a cloudy day

A chemical factory emitting smoke in the middle of a green rice field on a cloudy day

In a world grappling with climate change, patterns of energy use and associated emissions have taken center stage in discussions on firm performance. Energy use by industrial firms is a major driver of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, accounting for over 20% of direct emissions. The share is much larger once indirect emissions are included as well. Energy use not only affects a firm’s costs, but it also impacts the environment. To this end, researchers have adapted methodologies to study the relationship between management practices and energy demand at the firm level, albeit mostly in advanced economies (Bloom et al., 2010; Boyd and Curtis, 2014; Martin et al., 2012; Schweiger and Stepanov, 2019). Using the recent waves of World Bank Enterprise Surveys (WBES) in 31 countries, we build on this nascent literature to explore the link between firms’ management practices and energy use in a recent World Bank working paper.

Management practices may contribute to energy efficiency by easing information and coordination frictions and reducing the uncertainty in energy price fluctuations. This in turn helps reduce the costs associated with the adoption of green technology. Nonetheless, some management practices, such as setting production targets or monitoring related indicators, may conflict with physical energy use targets. Thus, the relationship between generic management practices and firms’ energy intensity is an open empirical question, which we examine in our study.

Do management practices correlate with energy efficiency in developing countries?

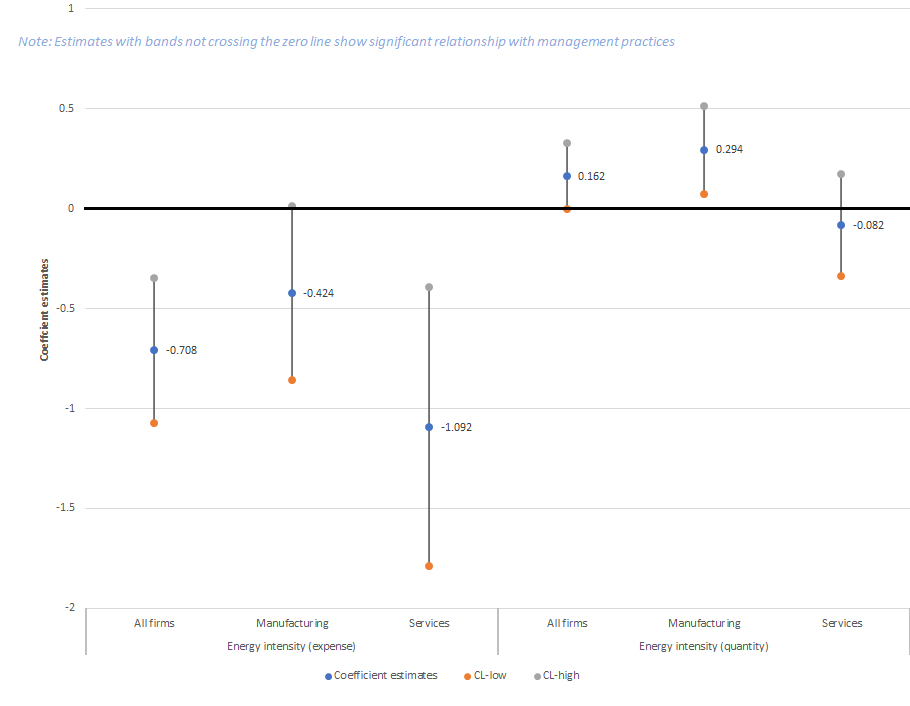

We find that while generic management practices negatively correlate with energy expenditure, they bear either a positive or no relationship to physical energy use, suggesting that management can help firms save energy costs without significantly reducing environmental impacts (Figure 1). These results are consistent with the findings of Schweiger and Stepanov (2019) for a set of countries in Eastern Europe. The basic argument is that management’s effect on energy intensity depends on factor costs: better managed firms conserve in the face of high prices but intensify use to take advantage of lower prices.

For many reasons, firms in developing countries, where the energy-management nexus has been rarely explored, may show a different relationship when compared to their counterparts in the developed world. They may, for instance, prioritize growth over environmental protection, although they may also be more sensitive to input costs. Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Shandong Province, China, suggests that firms rarely considered energy efficiency interventions with a payback period longer than one year (Karplus and Zhang, 2020). In India, an intervention that raised energy productivity of Indian manufacturing plants led to longer operating hours and greater demand for skilled labor and electricity, which likely increased environmental impact, considering the country’s high reliance on coal generation (Ryan, 2018).

Figure 1: Generic management is associated with lower energy intensity value but not necessarily lower physical quantity use

Notes: The figure presents rope ladder charts with coefficient estimates of a regression of energy intensity (value or quantity) on general management practices, including 3-digit sector and country fixed effects.

Which practices matter and for whom?

Among the structured management practices examined, target-setting practices are most strongly associated with reduced energy intensity expenditure in manufacturing, but not for services. None of the other management practices seem to matter for energy use in services, either. Our results differ from Boyd and Curtis (2014) for the United States, who document that effective monitoring, incentive structures and particularly lean manufacturing operations are associated with a reduction in energy use, while the implementation of production targets (conditional on other practices) increases energy consumption. The reason may be that the WBES definition of target-setting is broader and explicitly includes practices that could be related to energy savings such as “production volume, quality, efficiency, waste, or on-time delivery.”

On the contrary, monitoring practices in manufacturing may be positively correlated with energy intensity in physical quantity terms, perhaps because more energy-intensive firms are more motivated to invest in monitoring capabilities. As for services, we do not find evidence of an association of management with energy efficiency, either in value or in physical unit terms.

Do management practices encourage adoption of green practices?

Our paper documents an important stylized fact: Relative to generic management practices, a relatively small share of firms develop energy-centric management practices. Some examples of energy management practices include introducing target-setting and monitoring practices related to energy use, explicitly requiring adherence to energy conservation norms, rewarding employees who promote energy efficiency, emphasizing energy management as a priority, and encouraging innovation in controlling energy use.

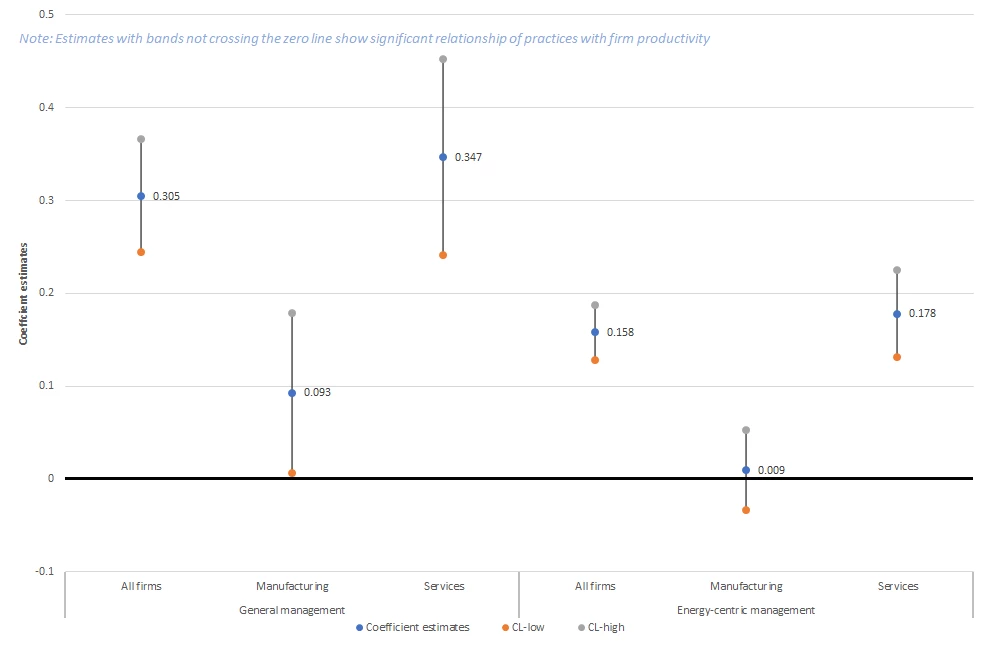

Our results suggest that threshold effects may exist in the adoption of energy-centric practices. General management score is correlated with stronger firm performance for both manufacturing and services, while the energy management practices are not correlated with firm performance in manufacturing (Figure 2). It may be that energy-saving opportunities in manufacturing firms are highly capital intensive, which imply large initial outlays and uncertain payback periods. By contrast, service firms may achieve energy savings through better coordination of knowledge and practice dissemination within the firm, without capital equipment modifications. The effect in the service sector is strongest among low knowledge intensity activities, which is comprised of transport, construction, retail trade, and hotels and restaurants. Explicit practices may translate into changes in employee behavior and cost savings for the firms without machinery or infrastructure upgrades, driving productivity gains.

Given the lower incidence in adoption of green practices among small firms, it seems that firms only consider introducing energy-centric practices once they are sufficiently large and have benefitted from adopting better management practices. Manufacturing firms show no relationship between energy management and productivity, which is consistent with limited incentives to make investments in energy-centric practices.

Taken together, our findings suggest that interventions aimed at improving energy management should be tailored to firm circumstances. A deeper investigation of the barriers (e.g., administrative costs, credit constraints etc.) that prevent firms from adopting energy management practices could aid in the design of informational or financial interventions that could help overcome the energy-efficiency gap.

Figure 2: While general management practices correlate with higher firm productivity in manufacturing, energy-centric ones do not

Notes: The figure presents rope ladder charts with coefficient estimates of a regression of firm productivity on management practices (general and energy-centric in separate regressions), including 3-digit sector and country fixed effects.

Join the Conversation