In a new paper published in the World Bank Working Paper Series: “Debiasing

on a Roll: Changing Gambling Behavior through Experiential Learning” (

WPS #7195, February 2015), my co-authors and I study how we can start using insights from the biology of the human mind to better understand and facilitate learning of key development concepts especially among illiterate populations in poor countries.

The premise of our research can be explained with a simple example. Lets talk fast cars. Ferrari is a fast car -- it can accelerate from 0 to 100 mph in less than 7 seconds and can reach upwards of 220mph. But how fast is that really? Imagine my job was to convince you that 220mph is really fast. How would I go about doing that? I could give you data on specs and performance, perhaps show you pictures of how big the Ferrari engine is, or draw comparisons for you with something you think of as being fast (say a Cheetah) so you can appreciate the car’s acceleration. Alternatively, I could put you in a Ferrari with a professional race car driver and have you experience 220mph. Which do you think will be more effective in gaining an appreciation of speed?

Clearly the latter! The reason is in the biology of our brain and the way we learn. The experience of a Ferrari stands out. It is concrete and salient. It provides opportunities for instantaneous reflection and updating of prior beliefs. And finally it is memorable without having to tax the cognitively heavy systems of attention or memory. Because of these factors, the Ferrari experience will likely stay with you for a very long time.

We take this idea of experiential learning and apply it in South Africa as a debiasing instrument to encourage households against playing the national lotto. From a development perspective, this is an important question – previous studies have shown that gambling crowds out a significant proportion of household consumption and lotteries in particular are a hugely regressive tax with poorer households spending a much larger share of their income on lottery tickets. Yet the likelihood that they would ever win the big prize is very small. So the natural question is why people buy lottery tickets if they are such a bad deal?

Turns out that playing the lottery is an example of where our human brain deceives us. Research in psychology and economics has shown that individuals tend to grossly overestimate small winning odds especially when such small odds are unlikely to be experienced in any other aspect of our lives. This concept is implied from Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect theory. The lotto also makes winning more attainable to everyone by showcasing winners who are ordinary folks, like the grocery store clerk. Moreover, the lotto advertises big, ringing bells, popping balloons, and printing big checks for local winners on TV. So individuals believe that winning the lotto is actually available to them -- this is called the availability bias.

So the research question is how can we debias individuals away from playing the lottery? Tools such as traditional financial literacy and rules of thumb are unlikely to affect the psychological biases that drive lottery purchases, especially since teaching individuals the concept of probability is extremely challenging when they do not even understand basic math. But how about making people experience probability? Just as in the case of the Ferrari where we developed an appreciation for speed, we can develop an appreciation for winning odds. In our research, we basically followed the fundamentals of a four stage learning cycle model common in psychology and played a simple dice game that provided a concrete and salient experience about probabilities and winning odds.

In the game each player started with one die and rolled till she got a six, then she was handed two dice and rolled till she got two sixes which on average took her much longer. Depending on how fast she was able to roll two sixes, she could reflect and update her beliefs about winning odds. Immediately afterwards, she was told that winning the lotto would be equivalent to her rolling all sixes on nine dice! Importantly, this experience involved no computations or math.

We played this simple game in rural South Africa in a RCT involving 840 individuals. The research design allowed for two levels of exogenous variation, first that allocated individuals to treatment and control groups, and the second that determined treatment intensity depending on how many rolls it took players to get two sixes, which was instantaneously random.

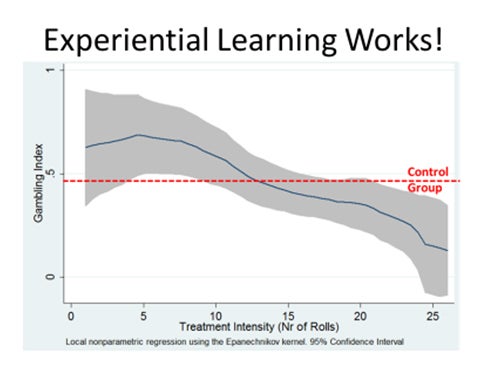

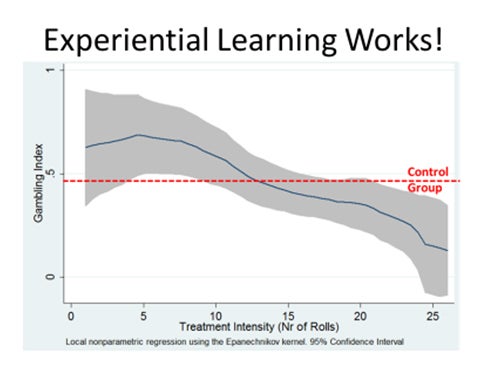

To assess impact of this treatment, we measured lottery outcomes several times over a 12 month period with immediate outcomes and then at 6 months and 12 months. What we find is very stark and the main results are best depicted in the graph below. Those players who took a long time to get two sixes, the high treatment intensity group on the right half of this graph, ended up playing the lottery significantly less than the control group, and hence were effectively debiased up to 12 months after the treatment. However, what we also find is that those players who got lucky in our game and happened to roll sixes in fewer number of tries, the left half of this graph, actually ended up playing the lotto more than the control group. The heterogeneity based on treatment intensity allows us to identify the impact as coming from updating of beliefs about lotteries.

Overall, our paper shows that experiential learning can be a powerful tool for policy – the perverse effect of reinforced biases could easily be avoided by extending the game to three dice. If we circle back to the biology of the mind and the way we learn, there is room for individuals to learn concepts and actively experiment and observe outcomes and quickly learn from mistakes. Clearly this is a promising and fertile area for further research especially in other areas of development such as technology adoption.

The premise of our research can be explained with a simple example. Lets talk fast cars. Ferrari is a fast car -- it can accelerate from 0 to 100 mph in less than 7 seconds and can reach upwards of 220mph. But how fast is that really? Imagine my job was to convince you that 220mph is really fast. How would I go about doing that? I could give you data on specs and performance, perhaps show you pictures of how big the Ferrari engine is, or draw comparisons for you with something you think of as being fast (say a Cheetah) so you can appreciate the car’s acceleration. Alternatively, I could put you in a Ferrari with a professional race car driver and have you experience 220mph. Which do you think will be more effective in gaining an appreciation of speed?

Clearly the latter! The reason is in the biology of our brain and the way we learn. The experience of a Ferrari stands out. It is concrete and salient. It provides opportunities for instantaneous reflection and updating of prior beliefs. And finally it is memorable without having to tax the cognitively heavy systems of attention or memory. Because of these factors, the Ferrari experience will likely stay with you for a very long time.

We take this idea of experiential learning and apply it in South Africa as a debiasing instrument to encourage households against playing the national lotto. From a development perspective, this is an important question – previous studies have shown that gambling crowds out a significant proportion of household consumption and lotteries in particular are a hugely regressive tax with poorer households spending a much larger share of their income on lottery tickets. Yet the likelihood that they would ever win the big prize is very small. So the natural question is why people buy lottery tickets if they are such a bad deal?

Turns out that playing the lottery is an example of where our human brain deceives us. Research in psychology and economics has shown that individuals tend to grossly overestimate small winning odds especially when such small odds are unlikely to be experienced in any other aspect of our lives. This concept is implied from Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect theory. The lotto also makes winning more attainable to everyone by showcasing winners who are ordinary folks, like the grocery store clerk. Moreover, the lotto advertises big, ringing bells, popping balloons, and printing big checks for local winners on TV. So individuals believe that winning the lotto is actually available to them -- this is called the availability bias.

So the research question is how can we debias individuals away from playing the lottery? Tools such as traditional financial literacy and rules of thumb are unlikely to affect the psychological biases that drive lottery purchases, especially since teaching individuals the concept of probability is extremely challenging when they do not even understand basic math. But how about making people experience probability? Just as in the case of the Ferrari where we developed an appreciation for speed, we can develop an appreciation for winning odds. In our research, we basically followed the fundamentals of a four stage learning cycle model common in psychology and played a simple dice game that provided a concrete and salient experience about probabilities and winning odds.

In the game each player started with one die and rolled till she got a six, then she was handed two dice and rolled till she got two sixes which on average took her much longer. Depending on how fast she was able to roll two sixes, she could reflect and update her beliefs about winning odds. Immediately afterwards, she was told that winning the lotto would be equivalent to her rolling all sixes on nine dice! Importantly, this experience involved no computations or math.

We played this simple game in rural South Africa in a RCT involving 840 individuals. The research design allowed for two levels of exogenous variation, first that allocated individuals to treatment and control groups, and the second that determined treatment intensity depending on how many rolls it took players to get two sixes, which was instantaneously random.

To assess impact of this treatment, we measured lottery outcomes several times over a 12 month period with immediate outcomes and then at 6 months and 12 months. What we find is very stark and the main results are best depicted in the graph below. Those players who took a long time to get two sixes, the high treatment intensity group on the right half of this graph, ended up playing the lottery significantly less than the control group, and hence were effectively debiased up to 12 months after the treatment. However, what we also find is that those players who got lucky in our game and happened to roll sixes in fewer number of tries, the left half of this graph, actually ended up playing the lotto more than the control group. The heterogeneity based on treatment intensity allows us to identify the impact as coming from updating of beliefs about lotteries.

Overall, our paper shows that experiential learning can be a powerful tool for policy – the perverse effect of reinforced biases could easily be avoided by extending the game to three dice. If we circle back to the biology of the mind and the way we learn, there is room for individuals to learn concepts and actively experiment and observe outcomes and quickly learn from mistakes. Clearly this is a promising and fertile area for further research especially in other areas of development such as technology adoption.

Join the Conversation