After years of bad news from developing countries about high rates of health worker absenteeism, and low rates of delivery of key health interventions, along came what seemed like a magic bullet: financial incentives. Rather than paying providers whether or not they show up to work, and whether or not they deliver key interventions, doesn’t it make sense to pay them—at least in part—according to what they do? And if, after doing their cost-benefit calculations, women decide not to have their baby delivered in a health facility, not to get antenatal care, and not take their child to be immunized, then doesn’t it make sense to try to change the benefit-cost ratio by paying them to do so?

Financial incentives in health have taken off

Much of the developing world has said Yes to the first question, and many developing countries have said Yes to the second as well. Donors have agreed. Since 2007, they’ve given $436 million to the World Bank to spend on projects that help governments move away from budgets and salaries (monies that get paid irrespective of performance) to a mix of budgets, salaries and bonus payments linked to results. Most of the $436 million are supporting pilot performance-based financing (PBF) projects in low-income countries. The funds are leveraging $2.4 billion to support project implementation from the International Development Association, the arm of the World Bank that provides concessional lending to low-income countries.

Financial incentives on the demand side have also been introduced—for example, payments to women who deliver their babies in a public facility. Sometimes, programs have financial incentives on both the supply and demand sides: incentivizing providers may not help much if families find visiting public facilities too costly; and incentivizing families may not help much if providers don’t show up to work.

Skimpy evidence to date

So far, despite the widespread hope that financial incentives are a magic bullet for developing countries, and despite the large financial commitments, the evidence is still pretty skimpy.

Two reviews of demand- and supply-side incentives, one by the Cochrane Collaboration, the other by the German Development Institute, concluded that little could be said definitively from the 21 programs studied, partly because the evaluation methods were weak. A more recent review of demand-side measures was more upbeat, but still pointed out lots of areas where we know too little.

The World Bank’s PBF projects will help fill the knowledge gap. All but eight of the 42 projects (six of which are standalone studies of middle-income programs) are scheduled to produce an impact evaluation, many using a prospective randomized control trial (RCT) design. To date, however, only three have done so. They found mixed results: in one country (DRC) no impacts were seen; in the others (Argentina and Rwanda), positive impacts were found, but not on all indicators. The other 31 PBF projects will produce useful evidence, but we won’t get the results for months, and in many cases years.

Partly because it’s going to take a while before we see the results, we probably shouldn’t rely exclusively on these and other prospective studies. It would be good to know more now about what works rather than wait several years. After all, now is when countries are looking to make some pretty big investments.

There’s another reason not to pin all our hopes on these prospective studies: it’s likely there will be quite a few questions they won’t give us answers to. We won’t have a good sense of whether the results will hold as the program is taken from the experimental phase and scaled up nationally. And it’s likely there will be some important design questions that these experiments won’t be able to address—because the experiment is too small, or because the resources aren’t available, or because the questions are considered ‘second-order’, and the people responsible for the projects are keen to focus on what they see as the ‘first-order’ question of whether financial incentives ‘work’.

Can’t we learn more now by doing more and better retrospective studies?

Three recent papers take a different tack to the prospective RCT. And while they don’t conclude that financial incentives in health do not work, they do suggest that financial incentives aren’t quite the magic bullet many hoped they would be.

These studies are retrospective studies of at-scale (or almost at-scale) programs. RCTs ‘identify’ program effects through randomized assignment to different ‘treatment’ groups. Retrospective studies of at-scale programs can’t use that ‘identification strategy’. What they can do, though, is exploit the fact that these programs weren’t implemented overnight everywhere, but instead rolled out first in some places, then others, and so on. By comparing changes in outcomes over time between households already exposed to the program and those not yet exposed, adjusting for differences in ‘covariates’ between the already ‘treated’ and the as-yet ‘untreated’, researchers are able to estimate the effects of the programs on key outcomes.

One of these retrospective studies looks at PBF in Cambodia—the first developing country ever to do PBF (the first scheme started in 1999). Cambodia is also the country that has tried the most ‘flavors’ of PBF. Sometimes, depending on the time periods and locality, PBF has been accompanied by demand-side incentives, and sometimes the MOH has contracted with NGOs either to provider care or manage MOH facilities. All PBF programs in Cambodia have specified performance targets for antenatal care (ANC), delivery in a public facility, childhood immunization and the use of birth-spacing methods.

The second study looks at Burundi whose PBF program aimed to improve maternal and child health outcomes, and was rolled out across the country between 2006 and 2010 in three waves. PBF payments account for around 40% percent of a facility’s revenue, and are linked to various output indicators including ANC, vaccinations and family planning.

The third study looks at the developing world’s largest demand-side incentive program: the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) scheme in India, which provides cash to women who give birth in a public health facility. The amount varies between urban and rural areas, and between states, but the sum paid is typically at least as much as women usually pay to have their baby delivered in a government facility (around $25). (Women are supposed in principle to be able to get the cash if they deliver in an approved private facility, but in practice this part of the scheme hasn’t yet started working.) The program also provides a cash payment to accredited health workers who attend a delivery in a public facility.

Call it magic?

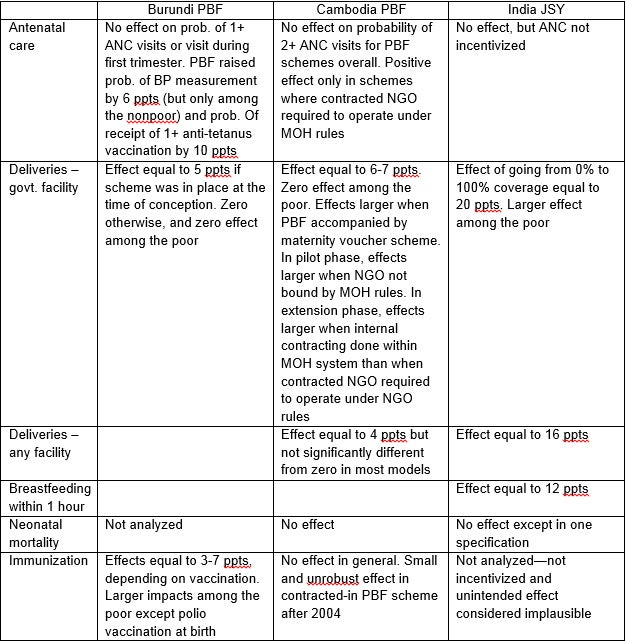

Looking down the columns of the table below where the results of three studies are summarized, it’s clear that India’s demand-side program comes the closest to delivering what it was supposed to—getting women, especially poor women, to deliver in a facility. It also encouraged breastfeeding, which wasn’t incentivized by the program. Despite this, however, JSY had no effect on neonatal mortality. This is significant given today’s report on child mortality from UNICEF, WHO and the World Bank, which concluded that the neonatal period remains the biggest challenge in reducing under-five mortality. The report found that deaths in the first 28 days now account for 45% of deaths among under-fives, and that neonatal mortality has fallen more slowly than postnatal under-five mortality (47% compared with 58%).

The two PBF programs did less well. There’s only one unambiguously good result—Burundi’s PBF scheme raised immunization rates, and achieved bigger increases (for most types of vaccination) among the poor. The rest of the table is mixed news, or plain bad news. The mixed news is that in Burundi PBF had some impact on ANC content but not on ANC visits, and that in both Burundi and Cambodia PBF raised government-facility deliveries but only among the nonpoor. The plain bad news is that PBF in Cambodia basically had no impacts on ANC, facility deliveries overall, immunization, or neonatal mortality—this despite the fact that several of the PBF schemes received a higher level of spending per capita.

Why not so magic?

PBF design matters. The Cambodia study suggests that the structure of incentives and the degree of autonomy providers have likely makes a difference—results were worse under a halfway-house arrangement where an external contractor had some but not complete autonomy; in places where this didn’t happen, even if the contracting was internal to the MOH, impacts were more likely to be found.

Demand-side and supply-side incentives work on different margins—demand-side incentives encourage people to go to a facility, while supply-side incentives encourage health providers to deliver more and better care to people who have made it to the facility. This helps explain why in Cambodia PBF worked better when accompanied by a maternity care voucher scheme, why in Burundi PBF affected the content of ANC but not the number of visits, and why in India the demand-side JSY scheme had such a large effect on facility deliveries, including among the poor. Demand- and supply-side incentives are complements, and are best combined; the evidence from these studies suggests that if only one is feasible, it might be better to go with the demand-side approach.

Crowd-out is underappreciated. In Cambodia and India, the scheme crowded out some private-sector facility deliveries. It’s not at all obvious this is a good thing. The government is using scarce resources to subsidize something people are willing to pay for, and may not be delivering better quality services. (Jeff Hammer has a nice blog post on this theme.) Standardized patients (the gold standard for assessing quality of care) haven’t been used to assess the quality of care in deliveries—unsurprisingly. But standardized-patient evidence from India for other casetypes suggests that private providers there are significantly more likely to ask the right questions and do the right exams, even if they are not more likely to prescribe the right treatment. We should at least be documenting the crowd-out and doing quality comparisons.

Last, given we’re ultimately concerned about outcomes, we need to secure impacts at all points along the results chain. In all three studies there was little or no effect on ANC. Yet we know that steps taken prior to childbirth can improve the survival prospects of neonates. There were effects on facility deliveries, but it may well be, as Jishnu Das has argued in a recent blog post, that the facilities we’re encouraging people to use through these schemes aren’t equipped to deliver the relevant intra- and postpartum interventions. In fact, they may be less well equipped than the private facilities the Cambodia and India schemes steered women away from. And further down the results chain, it’s likely that the various schemes didn’t do enough to increase the delivery of key community-based neonatal interventions. Using financial incentives to relieve one bottleneck isn’t much good if bottlenecks remain further up or down the results chain.

Join the Conversation