Chart with rising interest rates and percentages | © shutterstock.com

Chart with rising interest rates and percentages | © shutterstock.com

In a new paper, we analyze how U.S. monetary policy tightening can pose various challenges for emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). In a previous blog based on the same paper, we focused on the impact of rising U.S. interest rates on EMDE financial and economic conditions. This blog complements the analysis, exploring how increases in U.S. rates affect fiscal outcomes in EMDEs, and how those effects differ depending on the drivers of those increases.

We first identify three potential drivers of rising U.S. interest rates: (1) “real shocks,” which are prompted by improved prospects for U.S. economic activity; (2) “inflation shocks,” which reflect expectations of rising U.S. inflation; and (3) “reaction shocks,” which reflect investors’ assessments that the Federal Reserve’s reaction function has become more hawkish. We show that, over the past year, rising U.S. interest rates have been driven mainly by reaction shocks, as the Federal Reserve pivots toward more aggressive action to confront inflation (figure 1).

Figure 1: Underlying drivers of the increase in 2-year U.S. interest rate yields

Note: Shocks are estimated from a sign-restricted Bayesian vector autoregression (VAR) model with stochastic volatility. Figure shows cumulative change in underlying shocks and yields since January 2022. Inflation shocks are prompted by rising expectations of U.S. inflation. Reaction shocks are prompted by investors’ assessments that the Federal Reserve has shifted toward a more hawkish stance. Real shocks are prompted by anticipation of improving U.S. economic activity.

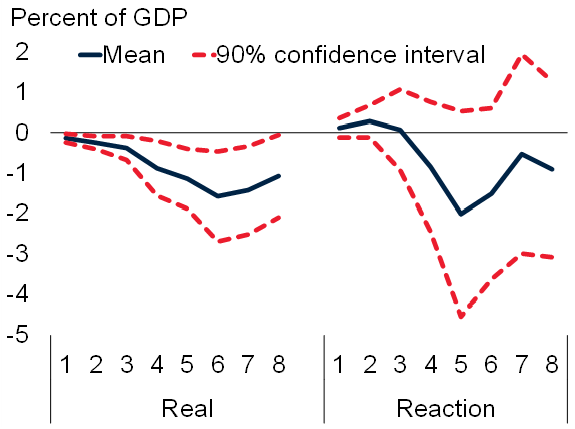

We then show that all these shocks affect fiscal conditions in EMDEs. However, their impacts differ, with reaction shocks leading to greater fiscal austerity. In particular, reaction shocks to U.S. interest rates are followed by an increase in the primary balance (smaller deficit or larger surplus; figure 2). This increase almost entirely reflects a sharp decline in government expenditure, most likely prompted by a tightening of the cost and availability of credit. In contrast, while real shocks are also associated with a significant increase in the primary balance, this reflects a rise in government revenues in addition to lower spending. Moreover, the decline in government spending due to real shocks appears to be markedly smaller than that due to reaction shocks, indicating that the latter leads to more pronounced austerity.

Figure 2: Impact of U.S. interest rate shocks on EMDE fiscal outcomes

Note: Figure shows impulse responses after one to eight quarters from panel local projection models with fixed effects and robust standard errors, to real shocks and reaction shocks. “Expenditure” and “Revenue” reflect the mean response of each variable to the underlying shock, come from separate models, and may not add up to the change in the primary balance. Dotted lines indicate 90 percent confidence intervals.

Through their effects on fiscal policy, both real and reaction shocks lead to a decrease in gross government debt levels in EMDEs , although such a decrease is statistically significant only in the case of a real shock (figure 3). The composition of debt is also affected by these shocks. In the case of a reaction shock, the composition shifts in ways that suggest a tightening of credit markets: the share of government debt held by external creditors declines and the share of short-term debt rises. Conversely, in response to a real shock, the share of government debt held by external creditors rises and the share of short-term debt declines, consistent with a loosening of global credit markets.

Figure 3: Impact of U.S. interest rate shocks on EMDE government debt

).

).

Join the Conversation