Market near Ramallah’s main mosque. Photo: Arne Hoel / World Bank

Market near Ramallah’s main mosque. Photo: Arne Hoel / World Bank

Amid weakening growth prospects and tightening global financial conditions, most emerging market and developing economies have limited fiscal space and greater exposure to international risk sentiment than before previous episodes of financial stress. In more than 80 percent of these countries, government debt is now higher than before the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Many of these economies need to urgently improve fiscal positions within credible medium-term fiscal plans and tilt borrowing towards longer maturities and domestic currency.

Emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) saw their fiscal space eroded significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic (Global Economic Prospects 2021). In the subsequent strong growth rebound of 2021, their fiscal positions improved. However, they now face a considerable risk of financial market stress accompanied by a sharp global downturn as major advanced-economy central banks increase policy interest rates to bring inflation back to target from multi-decade highs (Global Economic Prospects 2022; “Global Stagflation,” Discussion Paper, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London, 2022). Economic slowdowns may need to be smoothed with fiscal support measures and rising borrowing costs and currency depreciations may test governments’ ability to fund financing needs on sustainable terms.

An analysis based on the World Bank’s latest update of the Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space suggests reasons for concern about many EMDEs’ ability to weather the next financial shock (“A Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space”, Journal of International Money and Finance, 2022).

Some improvements in fiscal space in 2021

The pandemic-induced global recession of 2020 was the steepest since the Second World War, with a global output contraction of 3.3 percent. Propelled by unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus, the global economy grew 5.7 percent in 2021, its strongest rebound from any global recession in eight decades . This supported an improvement in fiscal positions around the world: government debt declined in more than one-half, and primary and overall fiscal balances increased in more than two-thirds of countries.

Advanced-economy government debt fell by 3 percentage points of GDP to 120 percent of GDP in 2021; the overall fiscal balance in advanced economies narrowed by 3 percentage points of GDP to 7.3 percent (Figure 1). In contrast to advanced-economy government debt, EMDE government debt rose by 1 percentage point of GDP, to 65 percent of GDP in 2021. This reflected developments in China where fiscal stimulus raised government debt by 5 percentage points of GDP.

Figure 1. Overall fiscal balances

Source: Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space Spring 2022 update

Note: Figure shows nominal GDP-weighted averages of overall net lending/borrowing per country group. LICs stand for low-income countries.

Elsewhere, in EMDEs (excluding China), government debt declined by 2 percentage points of GDP and fiscal deficits narrowed by 3 percentage points of GDP in 2021. This partly reflected strong growth amid still-benign financing cost in 2021. At historical interest rates and growth rates, government debt in EMDEs other than China would have remained on a rising trajectory in 2021, although the fiscal consolidation that would stabilize debt (1.0 percent of GDP) was considerably smaller than in advanced economies. In LICs, improvements have been more limited than elsewhere, in part because of their lagging economic recovery from the pandemic, but fiscal deficits have returned to 2019 levels.

But still less well-prepared for financial stress

Despite these improvements in fiscal positions, many EMDEs are more vulnerable to financial disruptions today than before previous episodes of disruptions . The Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space allows a comparison against three specific episodes of disruption: the 2007-09 global financial crisis, the 2014-16 commodity price plunge (for commodity exporters), and the 2020 pandemic.

Debt has skyrocketed over the past decade while sovereign debt ratings have been persistently downgraded in many EMDEs. Total debt (including both public and private debt) reached more than 130 percent of GDP last year (from roughly 95 percent in 2010). This was the largest increase in debt over a comparable period since the late 1980s. Since 2010, the median long-term sovereign debt rating was downgraded by more than one notch (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Total debt and sovereign debt ratings in EMDEs

Source: Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space Spring 2022 update

Note: Sample includes EMDEs excluding China. Total debt is defined as a sum of general government gross debt and domestic credit to the private sector and shown as nominal GDP-weighted averages. Sovereign debt ratings are presented as median.

The majority of EMDEs now have weaker fiscal positions than before these previous episodes of financial stress (Figure 3). Government (and private) debt and fiscal deficits are higher now than they were before the 2008-09 global financial crisis and the pandemic. The majority of EMDE government balance sheets is now more vulnerable to currency depreciation and international investor sentiment. In more than 60 percent of EMDEs, the share of foreign currency-denominated government debt has risen above pre-pandemic levels, and, in more than half of EMDEs, the share of nonresident-held government debt has increased.

Figure 3. Share of EMDEs with weaker fiscal positions than before the pandemic (2019) and before the global financial crisis (2007)

Source: Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space Spring 2022 update

Note: Figure shows the share of EMDEs in 2021 with higher government debt-to-GDP, lower overall fiscal balances in percent of GDP, higher private sector credit-to-GDP, higher foreign currency-denominated shares of government debt, higher nonresident-held shares of government debt, and higher short-term shares of external debt. The horizontal yellow line indicates 50 percent. The comparison in the share of foreign currency-denominated government debt between 2007 and 2021 is not computed, as data availability is quite limited in 2007.

The only dimension in which most EMDEs’ debt has become less vulnerable than before the previous episodes of stress is rollover risk, with a lower share of short-term external debt. This reflects in part the borrowing at longer maturities that was made possible by extraordinarily benign global financial conditions in 2020.

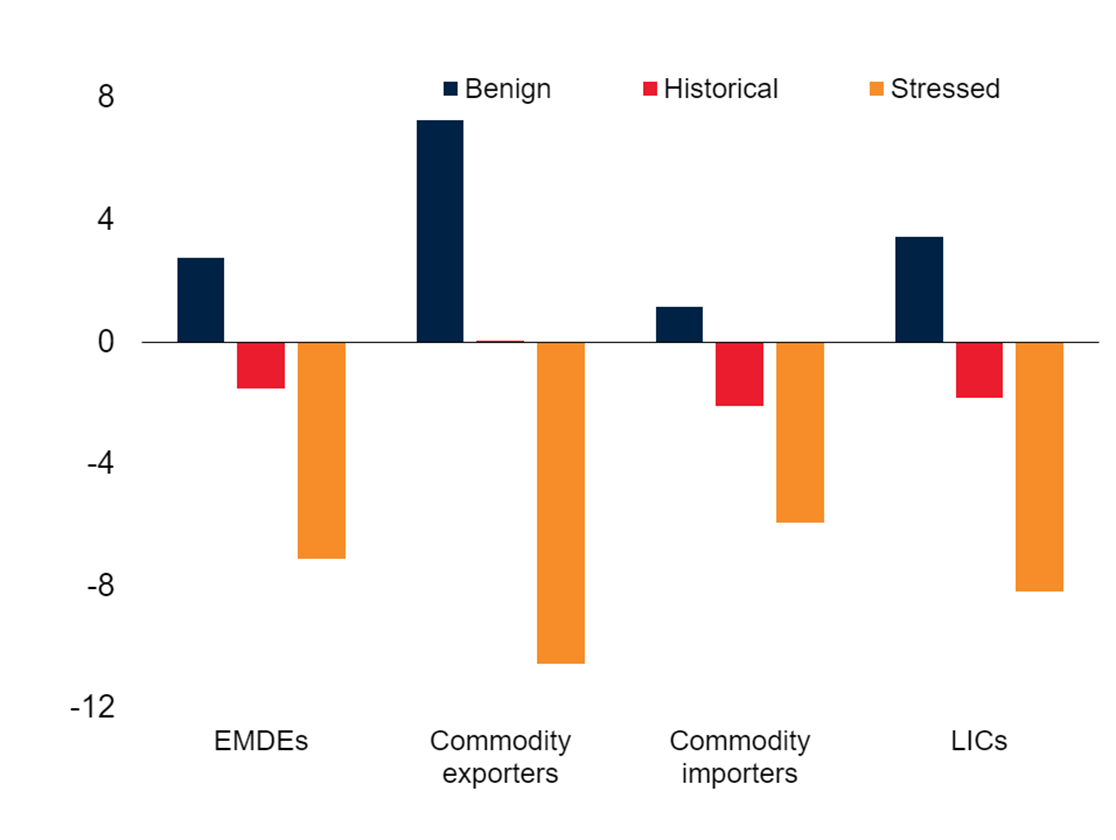

Another important metric, the sustainability gap, also suggests that EMDEs are vulnerable to financial stress (Figure 4). These gaps present a simple snapshot of adjustments that may be needed to reach debt targets under different scenarios involving GDP growth, interest rates, and reasonable debt levels. A positive gap refers to a “debt-reducing” trajectory whereas a negative one indicates a “debt-increasing” path. Only under benign conditions would fiscal positions be debt-reducing in most country groups; at historical average growth rates and interest rates, fiscal positions are debt-increasing across the board. Under stressed conditions, fiscal consolidation on the order of 7 percent of GDP would be needed in EMDEs (and 8 percent in low-income countries) to stabilize debt.

Figure 4. Sustainability gaps based on different assumptions

Source: Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space Spring 2022 update

Note: Figure shows nominal GDP-weighted averages of sustainability gaps under benign, historical, and stressed conditions in 2021. LICs stand for low-income countries.

Notwithstanding their recent windfalls from higher commodity prices, fiscal positions in commodity exporting EMDEs also remain more vulnerable than before the last commodity price slump, in 2014-16 (Figure 5). In 2014-16, a broad-based commodity price slide depressed growth in commodity exporters (“The Great Plunge in Oil Prices: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses”, Policy Research Note, World Bank, 2015; “Commodity Markets: Evolution, Challenges, and Policies”, World Bank, 2022). To rebuild fiscal space, energy exporters undertook a series of reforms to reduce subsidies, broaden tax bases, and improve business environments (Global Economic Prospects, 2020).

Figure 5. Share of commodity exporters with weaker fiscal positions than in 2013, before the commodity price slide of 2014-16

Source: Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space Spring 2022 update

Note: Figure shows the share of commodity-exporting EMDEs, energy-exporting EMDEs, or non-energy-exporting EMDEs in 2021 with higher government debt-to-GDP ratios, lower overall fiscal balances in percent of GDP, higher private sector credit-to-GDP, higher foreign currency-denominated shares of government debt, higher nonresident-held shares of government debt, and higher short-term shares of external debt in 2021. The horizontal yellow line indicates 50 percent. For energy-exporting EMDEs, the comparison in the share of foreign currency-denominated government debt and in the share of nonresident-held government debt between 2013 and 2021 is not computed, as data availability is limited.

Since then, however, in part due to the commodity price collapse during the pandemic, government debt has risen further in more than four-fifths of commodity exporters. Some of these economies have recently seen revenue windfalls because of elevated commodity prices. In most energy exporters, the composition of government balance sheets has also become more resilient. In most non-energy commodity exporters, in contrast, fiscal deficits have yet to be returned to pre-pandemic levels. The lion’s share of non-energy commodity-exporting EMDEs also has a larger fraction of foreign currency-denominated government debt and short-term external debt, making them vulnerable to depreciation and rollover risks.

Urgency of fiscal measures

EMDEs are facing tighter financial conditions and a higher likelihood of financial stress as advanced economies proceed with monetary policy tightening . There is still time for governments to guard against the risk of financial stress by improving fiscal positions within credible medium-term fiscal plans. A typical fiscal plan needs to include measures to expand the revenue base and to save revenue windfalls (in commodity exporters especially); review expenditures for priority items that need to be preserved and non-priority items that can be cut; and tilt borrowing towards longer maturities and domestic currency. This type of plan could be politically hard to implement during a global slowdown. However, considering the lessons of the previous stress episodes and vulnerable fiscal positions, EMDEs need to prepare for the worst by undertaking difficult measures while hoping for the best.

Join the Conversation