A women carries her child at a community health center amid coronavirus outbreak in Jakarta, Indonesia

A women carries her child at a community health center amid coronavirus outbreak in Jakarta, Indonesia

Nearly two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Bank’s High-Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS) in the East Asia and Pacific (EAP) Region show that poorer households have been disproportionately affected and have been slower to recover. Findings from the HFPS reported in the recent EAP Economic Update and a new regional study show that inequality has likely been exacerbated in several dimensions.

1. Poorer workers faced greater difficulty returning to work when pandemic-related mobility restrictions were relaxed

HFPS data collected in 11 countries in East Asia and the Pacific indicate that work stoppages have been closely associated with mobility restrictions in each country. Analysis using data on households’ pre-pandemic welfare status shows that periods of stringent mobility restrictions (low mobility) have been associated with higher levels of work stoppages that affected richer and poorer workers alike. As economies started to reopen and restrictions were loosened, however, poorer workers found it more difficult than wealthier workers to return to work (Figure 1, Table 1 column 1).

What could be driving these unequal employment impacts? During periods of stringent mobility restrictions, most sectors were affected. When mobility restrictions were relaxed, however, certain economic sectors such as professional and financial sectors (in which workers in the top 20 percent of the welfare distribution are more likely to work) were able to rebound more quickly. Nonetheless, sector of employment alone does not appear to explain differences. Even within the same sectors, workers from the top 20 were on average less likely to experience work stoppages during periods of higher mobility (Table 1, column 2), a pattern that also holds true when controlling for education levels (Table 1, column 3). Taken together, these results suggest that other differences across the welfare distribution within sectors (e.g., occupation, ability to work from home, job formality, job security) have likely contributed more to observed differences among the top 20 and bottom 20.

Figure 1. Poorer workers found it harder to resume work when mobility restrictions loosened

Source: EAP Economic Update, October 2021; Kim et al.,(2021); HFPS; Google Mobility Reports

Note: Work stoppage is defined as the share of respondents working pre-pandemic who were no longer working in the week preceding the survey. Quintiles reflect households’ pre-pandemic welfare and are created using country-specific national pre-pandemic welfare distributions. Each point represents a country round. The mobility index is an average of the percentage change in mobility to retail and recreation locations, transit stations, parks, and workplaces. The change is calculated relative to a pre-pandemic baseline. The regression line excludes outliers, namely Vietnam, where work stoppages were higher among wealthier workers, driven by higher participation by those in the poorer quintiles in agriculture, which was relatively less affected by the pandemic.

Table 1. Regression of work stoppages on mobility

Note: Work stoppage is defined as the share of respondents working pre-pandemic who are no longer working in the 7 days preceding the survey. The sample includes Indonesia, Lao PDR, Mongolia, Myanmar, Philippines, and PNG. Quintiles reflect households’ pre-pandemic welfare and are created using country-specific national pre-pandemic welfare distributions. Relatively normal (higher) mobility indicates an average mobility index above -20 percent. More stringent (lower) mobility indicates an average mobility index equal to or below -20 percent.

Source: Kim, et al. (2021); HFPS; Google Mobility reports

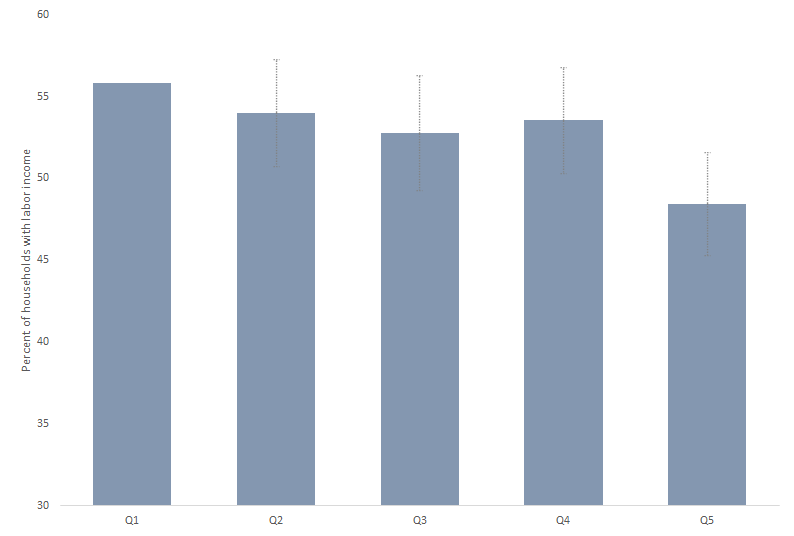

2. Income shocks have been widespread, but the wealthiest 20 percent of households have been relatively less affected

Household labor income losses have been significant across EAP countries. According to HFPS data, more than half of households report having experienced a reduction in wage or non-farm/farm business income since the previous survey round. Across countries, households in the top 20 percent of the welfare distribution were on average 7 percentage points less likely than poorer quintiles to experience a labor income decrease (Figure 2). Income losses from self-employment were more prevalent than reductions in wage income, but evidence suggests that much of the regressive gradient in labor income losses can be attributed to unequal shocks to wage income.

Figure 2. The wealthiest 20 percent of households were less likely to suffer labor income losses

Source: EAP Economic Update, October 2021; Kim et al., (2021); HFPS data from Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Mongolia, Myanmar, PNG, the Philippines, the Solomon Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Note: Pooled values are shown. Income losses are relative to the previous round. Conditional means controlling for country fixed effects are shown. 95% confidence intervals for the difference from Q1 are shown (rather than from zero).

3. To cope with pandemic-induced shocks, poorer households have been more likely to sell assets or increase debt

In addition to being more susceptible to employment and income shocks, poorer households have consistently been more likely to rely on coping mechanisms that can have negative long-term welfare consequences, such as selling scarce assets or engaging in strategies that increase debt. Across the sampled EAP countries, households in the bottom 20 percent that experienced a labor income shock were 10 percentage points more likely, on average, than those who faced shocks in the top 20 percent to resort to such measures (Figure 3). In contrast, households in the top 20 percent were, on average, 11 percentage points more likely than the bottom 20 percent to rely on savings to cope with pandemic-induced shocks.

Figure 3. Poorer households have relied more on coping mechanisms that increase their debt or involve the sale of scarce assets, whereas wealthier households have been more able to rely on savings

Source: EAP Economic Update, October 2021; Kim et al., forthcoming; HFPS data from Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Mongolia, Myanmar, PNG, the Philippines, the Solomon Islands, and Vietnam.

Note: Pooled values are shown. Coping mechanisms that increased indebtedness or involved the sale of assets include sold assets, sold livestock, credited purchases, delayed payments, or borrowed from friends, family, moneylenders, or other sources. Conditional means controlling for country fixed effects are shown. ninety-five percent confidence intervals for the difference from Q1 are shown (rather than from zero).

4. Poorer households may be at greater risk of long-term scarring, given higher rates of food insecurity

Rising food prices in several countries as well as widespread reliance on reduced food consumption as a way of coping with the pandemic’s effects have contributed to heightened food insecurity in the region, particularly among poorer households. HFPS data indicate that among households experiencing a decline in labor income, those in the poorest quintile were almost 3 times more likely than those in the wealthiest quintile to be food insecure (Figure 4). While conditions have improved over time in some countries, continuing food insecurity, particularly among poor and vulnerable households, may have serious long-term implications on children’s human capital development and future economic prospects.

Figure 4. Poorer households were more likely to be food insecure

Source: EAP Economic Update, October 2021; Kim et al., (2021); HFPS data from Cambodia, Indonesia, Mongolia, Myanmar, PNG, the Philippines, and the Solomon Islands.

Note: Pooled values are shown. Sample includes households that experienced labor income losses since the previous survey. Food insecurity here is defined as the share of households that reported that they had run out of food, went hungry, or were hungry but did not eat due to a lack of money or resources in the past 30 days. Conditional means controlling for country fixed effects are shown. ninety-five percent confidence intervals for the difference from q1 are shown (rather than from zero).

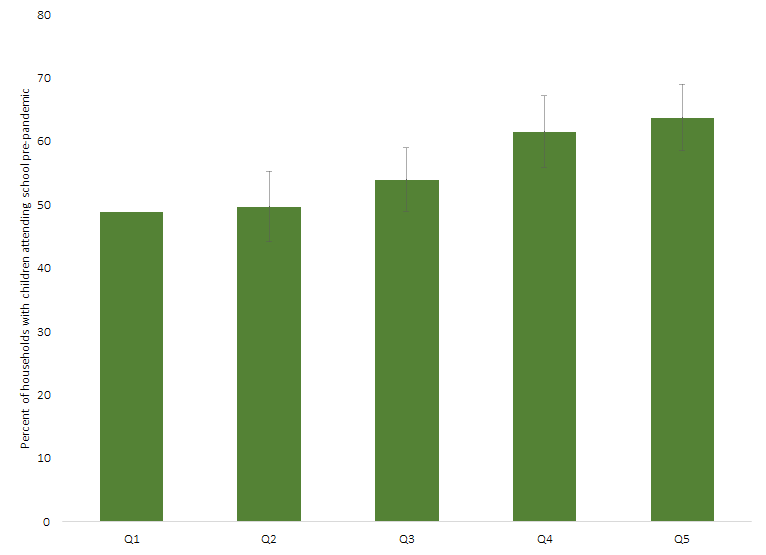

5. Poorer children are at greater risk of being left behind due to more limited interactive distance learning opportunities

Lower access among poorer students to educational activities that involve face-to-face learning or utilize online, mobile, or video platforms that enable interactive learning also risk widening welfare gaps in human capital accumulation with direct consequences on children’s future economic prospects. Across countries, households in the poorest quintile with children attending school pre-pandemic have been 15 percentage points less likely than those in the wealthiest quintile to have children engaged in interactive educational activities (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Children in poorer households have been less likely than those in wealthier households to engage in interactive educational activities

Source: EAP Economic Update, October 2021; Kim et al., (2021); HFPS data from Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Mongolia, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

Note: Pooled values are shown. Modes of interactive distance learning include mobile apps, online or in-person meetings/sessions with a teacher or tutor, or other online learning platforms. averages have been taken across rounds within each country. Education data are only available for round 4 in Myanmar and round 2 and 4 in Indonesia.

In sum, the pandemic appears to be increasing inequality in these five critical dimensions, threatening an inclusive and equitable recovery. Employment and income shocks have been more common and long-lasting among the poor than the non-poor. Coping mechanisms, such as the distress sale of household assets and increased debt, are likely making it harder for the poor to bounce back from the COVID shock. Moreover, food insecurity and limited opportunities to engage in interactive learning among poorer households raises the risk of increased child malnutrition and stunting and, thus, long-term losses in human capital and economic productivity.

Read More:

For more country-specific analysis on the COVID-19 impacts on households in East Asia and the Pacific region, please read the new working paper and the EAP Economic Update (October 2021).

Join the Conversation