A beneficiary of Nigeria LAPO Bank – largest microfinance investment in Africa

A beneficiary of Nigeria LAPO Bank – largest microfinance investment in Africa

Women, Business and the Law 2022 finds that globally the pace of legal reform for women’s economic inclusion is not moving fast enough. This implies a wasted opportunity, not only for women’s own empowerment but also for the economy and society at large. We are celebrating the tenth anniversary of the World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development (WDR 2012). Its message is as clear and true now as it was then: reducing gender inequalities is smart economics. Reforming laws for gender equality paves the way for changing social norms and actions. And the result is not only women’s empowerment but also a more resilient economy and stable society.

Women’s unequal position not only limits their progress but also makes them more vulnerable to shocks and crises, as the COVID-19 pandemic has painfully shown. Girls and women have been badly impacted by the economic crisis resulting from the pandemic, especially regarding access to education and participation in the labor force. It may not be surprising, then, that among the many new poor that the pandemic has caused, women are disproportionally affected.

But, as the WDR 2012 concluded, gender equality is not only good for women. The economy has better opportunities to grow and is more resilient to crises if women and men have equal rights. Discriminatory laws and legal inequality leave the full economic potential of our global and national economies untapped. No country can achieve its full potential without the equal economic participation of women and men. This concern drives our Women, Business and the Law project, whose latest edition was just released.

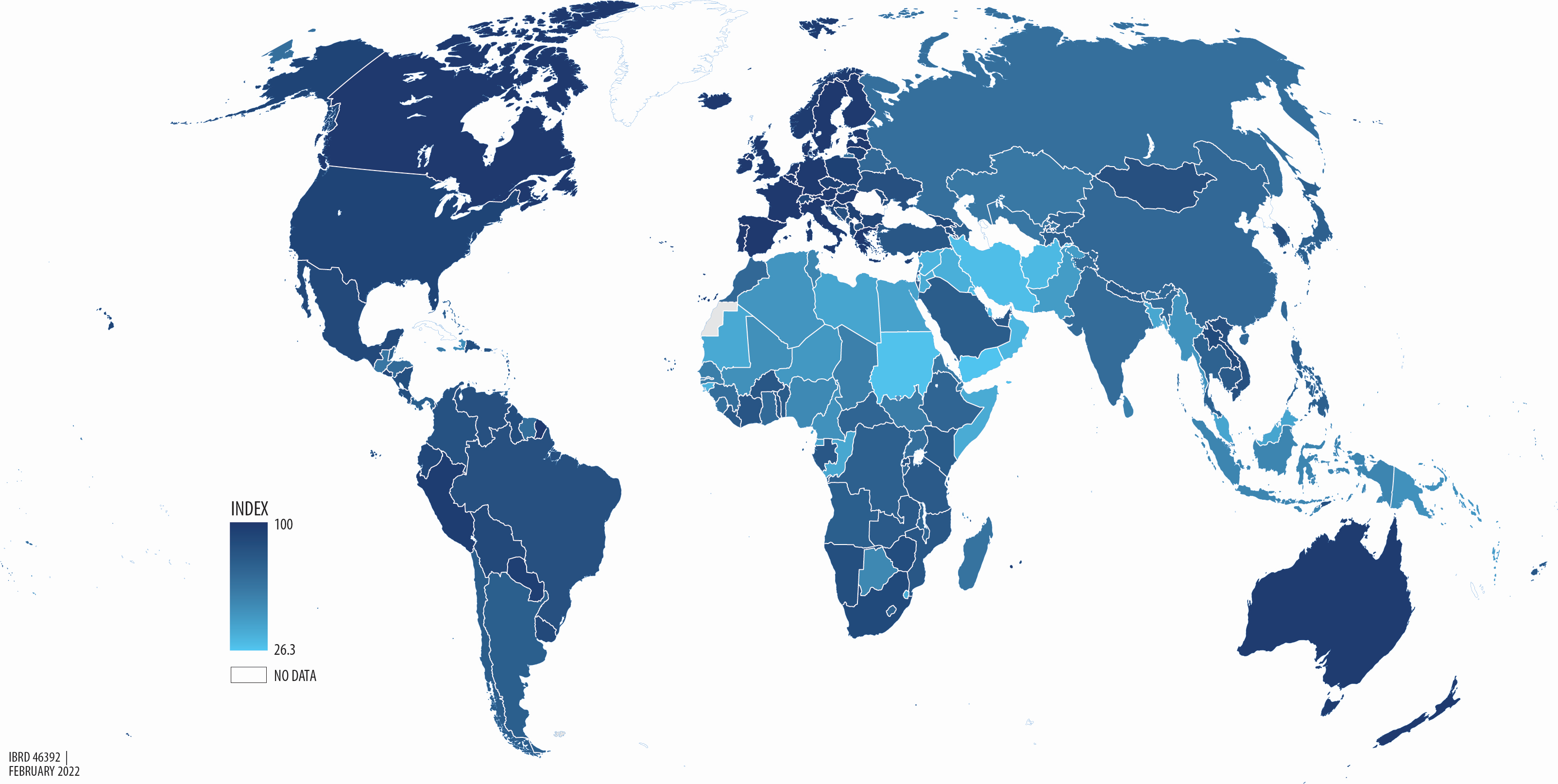

The global Women, Business and the Law index average is 76.5 out of 100. This means that 2.4 billion women of working age do not have equal economic opportunity and 178 countries maintain legal barriers that prevent women’s full economic participation (figure 1). Only 12 countries, all in the OECD, score 100 -- which means that women are on an equal legal standing with men across all eight areas measured: mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pension.

Figure 1. Women, Business and the Law 2022 Index

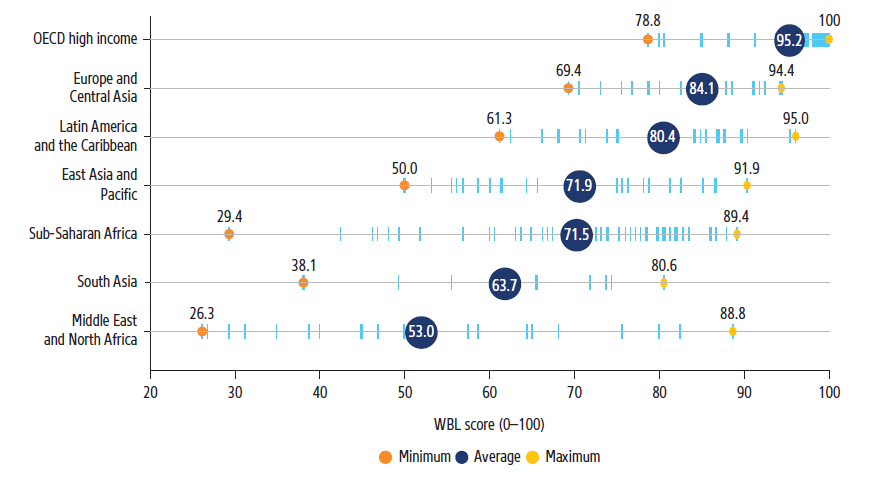

Over the past year, 23 economies prioritized gender equality and reformed their laws despite the pandemic. The Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa regions showed the largest improvements in the WBL Index, though these two regions still score the lowest overall (figure 2). Some countries have implemented large scale reforms. Gabon, for example, made comprehensive reforms to its civil code and enacted a law on the elimination of violence against women. And it is countries like Gabon that will reap the benefits of prioritizing equality.

Figure 2. Women, Business and the Law scores across and within regions

The Parenthood and Pay indicators remain the two indicators that countries are furthest behind overall (figure 3). Let’s consider the following facts. The average length of paternity leave is just one week. Only three economies grant the same amount of leave to mothers and fathers. In 95 economies, women are not guaranteed equal pay for equal work. In 86 economies, they face job restrictions that men don’t have. The good news is the most common reforms recorded last year were related to introducing or increasing paternity leave and shared parental leave. Women cannot achieve equality in the workplace if they are on unequal footing at home.

Figure 3. Average Women, Business and the Law scores, by indicator

Future blogs and analysis will highlight the findings of Women, Business and the Law pilot projects on childcare and measuring the law in practice. Here is a preview. The childcare pilot examines laws and regulations in 95 economies on the availability, affordability, and quality of childcare policies. It finds that the availability and regulation of childcare services vary widely across regions, not always in clearly discernable patterns. The implementation pilot, in turn, measures for the first time indicators “in practice” in 25 economies. It finds that on average, these economies have only half of the necessary structures in place to effectively bridge the large gap between laws on the books and real-life practice.

We welcome your engagement and participation in amplifying this message and joining Women, Business and the Law as part of the World Bank Group’s efforts to #AccelerateEquality around the world. Visit wbl.worldbank.org to learn more.

Join the Conversation