I think it’s fair to say most of us don’t typically take UN reports with us on our summer vacation. But you might want make an exception in the case of the high-level panel (HLP) report on the post-2015 development agenda. It offers a nice opportunity to reflect how – over the last 15 years or so – we have seen some serious global shifts in values, expectations and motivations.

The HLP feels the MDGs were worthwhile: “the MDGs set out an inspirational rallying cry for the whole world”. As my colleague Varun Gauri argues, goals inspire if they are underpinned by a moral case, and the panel pushes hard on issues of rights and responsibilities, social justice, and fairness: “new goals and targets need to be grounded in respect for universal human rights”; “these are issues of basic social justice. Many people living in poverty have not had a fair chance.”

The HLP realize we’re an ambitious generation, keen to leave our mark on the world, and unafraid of being bold. So they say: “After 2015 we should move from reducing to ending extreme poverty, in all its forms. … We can be the first generation in human history to end hunger and ensure that every person achieves a basic standard of wellbeing. There can be no excuses.”

The panel picks up on our growing commitment to universalism. It urges us to “leave no one behind” and “bring about more social inclusion”. The panelists say we need to do better on this than last time: “We should ensure that no person – regardless of ethnicity, gender, geography, disability, race or other status – is denied universal human rights and basic economic opportunities. We should design goals that focus on reaching excluded groups, for example by making sure we track progress at all levels of income.”

But universalism, says the HLP, means more that. The goals need to be broadly relevant – not just applicable to a few countries. And we need to realize that development goals are a shared responsibility – sustainable development is as much about what happens in North as what happens in the South.

All of this inevitably leads to a broader and more demanding set of goals – more topics, greater ambition, and more detail. The HLP feel the world wants this, and it’s probably right.

Which is why the report’s lackluster treatment of health comes as such a disappointment. It’s as if the teams working on the other topics got off to a great start in the post-2015 development goal “race” and never looked back, while the health team got stuck in the doldrums soon after the start, and the race organizers never thought to go and rescue them.

Disappointment in numbers

You can see what I mean from the two charts below.

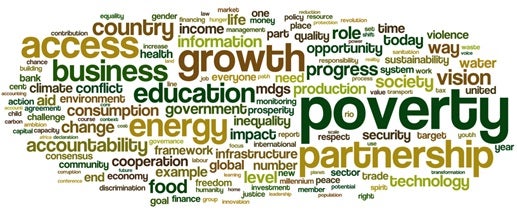

Fig 1 is a frequency distribution of nouns occurring in the main body of the report – the more frequently the word is used, the larger its size. (I dropped “development”, “partnership” and “goals” which are used a lot but aren’t topical.) If you look really hard, you can just see “health” – sandwiched between the much larger “business” and “growth”. Just below “health” is the much larger “education” and a little below that is the even larger “energy”. Even “food” is bigger than “health”.

Figure 1: How often are different nouns used in the HLP report on the post-2015 development goals?

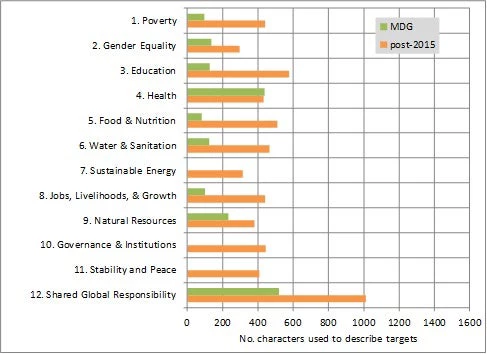

For Fig 2 I laid side by side – as best as I could – the new and old targets for the various MDG and post-2015 goals: tackling poverty, promoting gender quality, etc. (I used the new post-215 numbering.) I then counted the number of characters used in the text of each target and aggregated up to the level of the goal.

You can see in Fig 2 the expansion of the scope of the exercise, with in effect three new goals – 7, 10, and 11. You can also see how much more detail there is in the post-2015 goals than the MDGs. For example, the poverty MDG targets were described in just 96 characters; the post-2015 poverty targets take 440 characters to describe. This is true of all the goals except one: health. In this case there was actually a reduction in the number of characters – from 438 to 433. In fact, this is an undercount, because MDG target 8e (a shared global responsibility target) was “provide access to affordable essential drugs in developing countries”, and there is no new target on affordable drugs.

Figure 2: How many characters does it take to describe a development goal? MDGs vs. post-2015 goals

A not-so-great leap forward

The changes in Fig 2 reflect the increased ambitiousness and scope of the targets. For example, in the case of poverty, the $1.25-a-day target has been turned into a zero target (no extra characters for this part) but has also been supplemented by a target based on the national poverty line. In addition, three other targets have been added, one on rights to land, property, and other assets, another on social protection systems, and a third on building resilience and reducing fatalities from natural disasters.

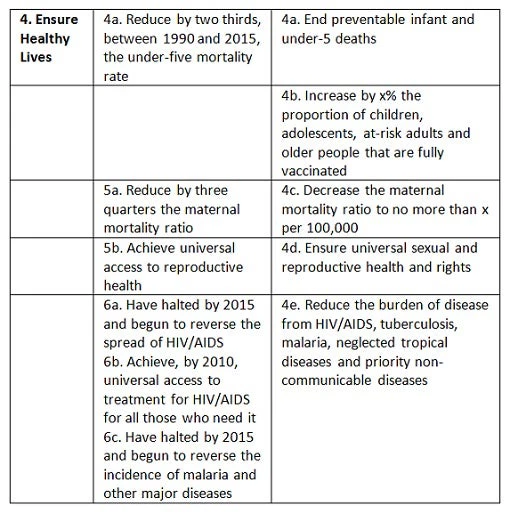

Table 1 below shows how the MDGs and post-2015 goals compare in the case of health. True there’s some added ambition – as with poverty, the post-2015 health goal includes a zero target. But otherwise they’re almost identical. A vaccination target has been added – hardly a great leap forward, given that childhood immunization was already a monitoring indicator in the MDGs. The only real hint of any new thinking is the addition of a target to “reduce … priority non-communicable diseases.” But it’s subsumed within an old target, and – coming right at the end of the list – looks very much like an afterthought.

Table 1: The health MDG’s and post-2015 targets compared

Not 1999

In fact there has been change – huge change.

Even in the 2000’s the health MDG’s weren’t very relevant to large swathes of the developing world. But with the recent global burden of disease report, we now know that the old and new targets (for they’re much the same) are even less relevant. Not only do the targeted causes of death combined account for a smaller share of disability-adjusted life years lost (or DALYs) than they did in 1999; they now account for less than 50% of DALYs in all regions except sub-Saharan Africa, and even there the picture is changing fast. So in a report that is striving for development goals that have universal appeal, we have a set of health targets that have even less salience than they did in 2000.

At the very minimum, the HLP might have had a set of targets for unfinished MDG business (eliminating preventable infant and under-five deaths, etc.) and then a second set of targets around NCDs that would have relevance across the globe – including in the richer North.

The panel could have gone further and taken a leaf out of the education sector’s book. We don’t set targets for a population’s knowledge and skills, but rather focus on whether children are in school and learning while they’re there. By analogy we could usefully have some targets defined in terms of outputs of the health system – it’s not the only contributor to health outcomes, but it’s one that people rightly expect to make a large impact on health, and one that governments have considerable control over.

The health system also causes a lot of frustration in many countries. It’s odd that none of this appears to have come through in the HLP’s consultations, because it came up a lot in the World Bank’s Voices of the Poor consultations – in the first volume, the word “health” crops up 245 times. And the concerns expressed there about poor quality services are reinforced by careful empirical work that shows the huge variation in the quality of medical diagnosis advice in the developing world – work that gives us some ideas about how service quality targets might be framed.

What happened to affordability?

There’s another dimension that’s completely missing in the HLP’s treatment of health, and one that’s been a big driver of change in the health sector in the last 15 years: financial protection.

A common lament in Voices of the Poor was the fear of financial catastrophe that ensues when a family is struck by illness or death. One aspect of this is the cost of getting treatment, especially hospital treatment which – as I reported in another post – can be financially ruinous for a poor family. Governments know that this worries people. China’s government embarked on its health reforms in 2003 precisely in response to opinion polls that showed huge discontent over the unaffordability of medical care. The dramatic worldwide push over the last 10 years on universal health coverage – documented in a series of recent World Bank studies – was prompted in no small part by governments wanting to provide better financial protection to their citizens. This is all missing in the HLP report, despite the fact that indicators of financial protection in health have been around for some time.

Together we can

It’s not too late to modernize the health angle to the post-2015 agenda. The MDG targets continued to be refined and extended long after the 2000 Millennium Declaration. And we haven’t even got to a post-2015 declaration yet.

So while you’re reading the HLP report on your vacation, have a think about what might go into a revised version of the health goals, and jot down your ideas in the comments section below. Together we might be able to come up with a post-2015 health agenda that is modern, ambitious and genuinely universal. Who knows, perhaps the Let’s Talk Development editor will offer a book token for the best comment? That way even if you work a bit on this year’s vacation, you’ll be able to relax on next year’s with a nice book.

Join the Conversation