Amanda Glassman’s blog post on Ghana’s health insurance program and the firestorm it produced (hat tip to Mead Over) is a reminder of the passions that health reform debates still generate. This is intriguing because my sense is that while we health-reform aficionados are berating one another in the blogosphere, policymakers in Asia are quietly iterating toward something of a consensus on a whole swathe of key issues on health reform. The process isn’t always driven by hard evidence, but that’s because there isn’t much hard evidence either way. I certainly don’t see compelling evidence against the emerging consensus—if that’s what it is. And what’s emerging is rather interesting.

1) More general-revenue financing

The idea of getting people—especially poor people—to make major contributions for health coverage seems to be fading. In China’s rural health insurance program which started in 2003 and aims to cover all rural households, the government initially asked households to pick up around 20% of the bill; now it’s down to 10% or less. The very poor contribute nothing. In India’s Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY) scheme, which targets the poor in most of India’s states and dates from 2008, the household pays just a nominal registration fee to join the scheme (around 5% of the combined registration fee and premium); the premium is paid by the taxpayer. In Andhra Pradesh’s Rajiv Aarogyarsi scheme, which started in 2007, the aim was initially to cover just the poor at the taxpayer’s expense; now virtually the entire population is covered. Indonesia’s Jamkesmas scheme which dates from 2008 covers the poor and nearpoor at the taxpayer’s expense. In the Philippines, “indigents” have been covered at the tax-payer’s expense since 1997 though it wasn’t until 2004 when there was a major push to cover all indigent households. In Thailand, everyone who isn’t a civil servant or formal-sector worker pays nothing under the universal coverage (UC) scheme which was launched in 2001. And in Vietnam’s health care fund for the poor which started in 2002, the taxpayer pays 100% of the enrollment cost; the near-poor pay 50% or less.

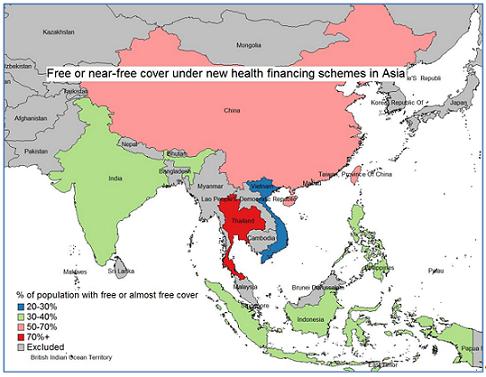

In these six Asian countries, over one billion people (around 40% of the population) have been covered by these new programs but have been asked to pay very little if anything toward the cost (see map for my estimates of coverage). In China, Indonesia and Thailand, the schemes extend well beyond poor families; this is true of Andhra Pradesh too, and to a lesser extent Vietnam.

2) More arms-length ‘purchasing’

All six Asian health financing programs entail a move away from the traditional model of general revenues being channeled through a health ministry to pay budgets and salaries to government health facilities. In China, a new entity—the new cooperative medical scheme—was set up within the health ministry with offices at the facility to deal with payments, based initially on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis but in some areas increasingly through prospective payments. In several parts of China, the scheme is now being operated by the agency that runs the health insurance scheme for formal-sector workers, albeit as a separate program. In India, the RSBY is operated by the ministry of labor, and the day-to-day running of the scheme is contracted out to private insurers on a competitive bidding basis, as happens in Andhra Pradesh; providers are paid on a DRG-type basis. In Indonesia, the health ministry runs the program, but providers are paid capitation at primary level and negotiated fees at secondary level. In the Philippines, the social health insurance agency, PhilHealth, pays providers through a FFS system. In Thailand, a semi-autonomous national health security office oversees the UC program, and pays providers through a mix of capitation and DRGs. Finally, in Vietnam, cover is organized through the social security agency that reimburses providers mostly on a FFS basis but in some areas through capitation or DRGs.

The tax-financed coverage expansion in these countries was thus used as an opportunity to create a wedge between the provision of health care and its “purchasing”, and to alter the way providers are paid by shifting to a performance-related payment system.

3) A reduced emphasis on government provision

While all countries appear to be firmly moving toward a greater role for government in the finance of health care, many are firmly reducing the emphasis on government in the provision of health care. In India, private hospitals are contracted by both the RSBY and Aarogyarsi schemes. (In India’s case, as already mentioned, the role of government has been scaled back too in the purchasing of health care.) In Indonesia, 30% of hospitals contracted in the Jamkesmas scheme are private. In the Philippines and Thailand, private hospitals provide care to those covered at the taxpayer’s expense. This is starting to happen too in Vietnam, though not in China where in any case the distinction between public and private is somewhat blurred.

4) An emerging model with merits?

The coverage expansion in these countries was thus not just about expanding coverage and delinking provision and purchasing with performance-related payments; it was also about bringing in the private sector to provide care to people whose coverage is being financed by the taxpayer. Asia’s recent health financing initiatives are living proof of the point many of us have tried to make over the years—financing health care one way (e.g. through general revenues) doesn’t limit the choices open to you in delivering health care.

The shift away from contributions is potentially good for equity because it delinks entitlements and ability-to-pay. The schemes don’t eliminate out-of-pocket payments altogether, of course, because the coverage isn’t always comprehensive (schemes like RSBY focus on inpatient care and most don’t cover OTC drugs), and copayments are levied (copayment rates initially in China were well over 50%). But the trend to public finance seems a good one from both equity and efficiency perspectives.

The purchaser-provider split and the shift to performance-based payment have their champions, and there are certainly reasons to hope that such approaches could improve efficiency. But one would certainly be naïve to think that they are problem-free—a purchaser-provider split is costly to operate, and performance-related payments risk incentivizing providers in the wrong direction. That said I don’t think we can say the jury has returned with a verdict either way, on either idea. Asia’s experiences will help the jury make up its mind.

Allowing private providers to deliver publicly-financed care is an interesting twist. Much of the passion surrounding the role of the private sector in health care arises in the context of patients paying private providers out-of-pocket or through private insurance. The concerns that arise there (e.g. ill-informed patients being exploited financially by better-informed providers) seem likely to be less of an issue when the care is being financed by the taxpayer.

So, while we aficionados have been debating health reform passionately among ourselves, Asia’s policymakers have quietly got on with the business, and have come up with a rather interesting model. It’s work in progress, of course, and not without its challenges. But it might just be a model that a lot of policymakers might like. Let’s see if it works!

Join the Conversation