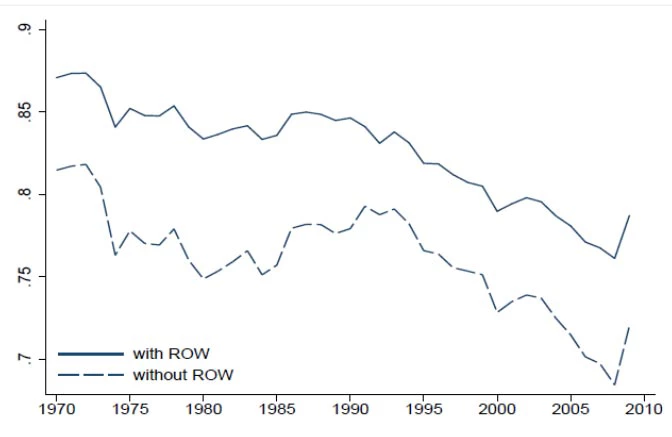

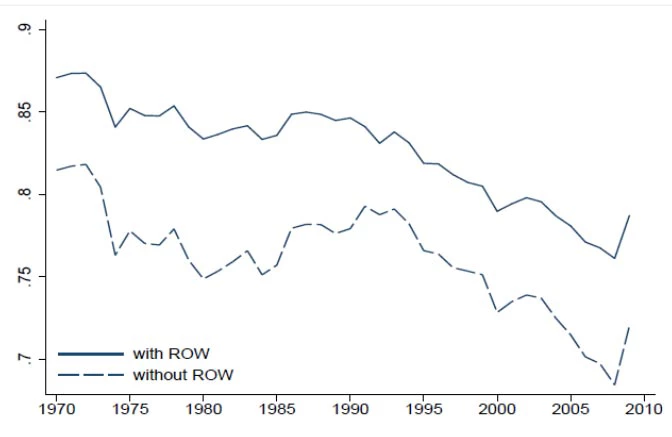

The last few decades have witnessed the rise of global value chains (GVC), with factories being set up in the faraway countries, such as China, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Mexico, producing and shipping products for the US and EU markets. Typically, being part of a GVC entails firms importing materials and intermediate products for further processing before exporting to other countries. This implies that, together with the engagement of GVCs, these countries most likely face the inevitable decline in their domestic value added embedded in their exports (see Figure 1). In other words, less value is being generated and captured locally for each dollar of exports, despite the tremendous rise in the overall value of exports due to GVC participation. All else equal, most developing country countries would prefer to increase its domestic value added in their exports in order to boost the gross domestic products of their economies and hence the general wellbeing of the countries. Most countries want to “move-up the value chains.” The question is how.

Figure 1: Value Added to Gross Export (VAX) Ratios Across the World

Source: Johnson and Noguera (2014)

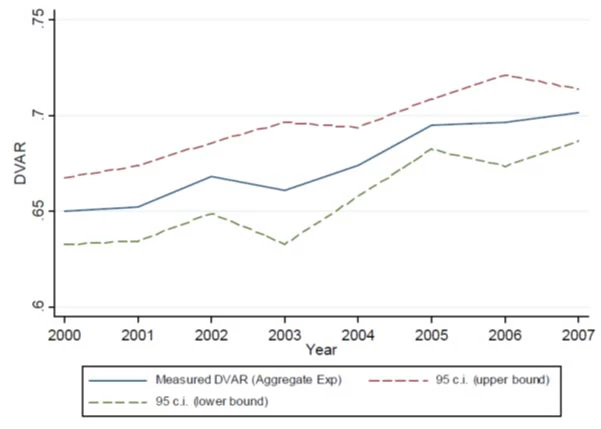

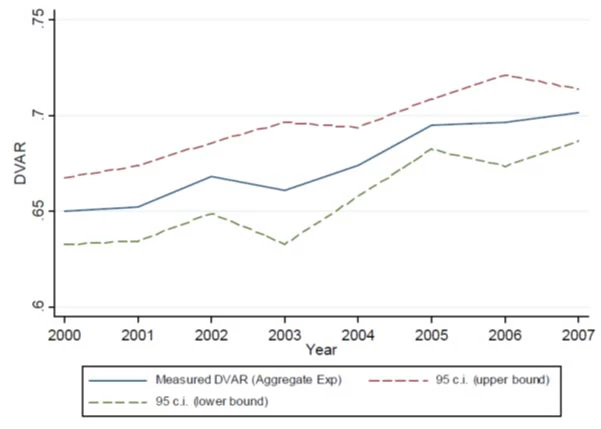

In a recent Bank study based on firms and customs transaction level data, Kee and Tang shows that China is an intriguing exception to the global decline depicted in Figure 1, despite its deep engagement in global value chains. The share of domestic content in Chinese exports has risen from 65% in 2000 to 70% in 2007 (see Figure 2). The increase is even sharper for the processing sector, which has the share of domestic content improved from 46% in 2000 to 55% in 2007. The study also finds that the increase in the domestic value added in Chinese exports is mainly driven by individual processing exporters substituting domestic for imported materials, both in terms of volume and varieties. Other factors, such as rising wages, changing composition of Chinese exports towards the high-DVAR industries or the non-processing sector, or firm entry and exit, cannot explain the upward trend during the period of the study. This evidence is consistent with China moving-up the GVC with a more sophisticated domestic intermediate product sector supporting the downstream processing export sector.

Figure 2: Domestic Value Added in Exports for China (2000-2007)

Source: Kee and Tang (forthcoming)

How has China moved up the GVC? Detailed firm-level analysis by Kee and Tang (forthcoming) suggests that this is accomplished through a structural transformation fused by trade and FDI liberalization of China since 2000. Such liberalization encouraged intermediate input producers in China to expand their product varieties, similar to what has been found in India by Goldberg et al. (2010), and in Bangladesh by Kee (2015). As such, exporters in China buy more domestic intermediate inputs and rely less on imports. Overall, trade and FDI liberalization can explain a bulk part of the increase in domestic value added in Chinese exports.

For policymakers interested in promoting domestic value added in exports, the findings of this study suggest that conducive trade and FDI policies are very important. Particularly, the study provides empirical support for the idea that designing policies to attract FDI with significant backward linkages may help promote intermediate input industries while also benefitting domestic final goods firms and raising their domestic value added.

For a related column, please refer to http://www.voxeu.org/article/china-and-global-value-chain-new-evidence. Also available as World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (WPS 7491).

-------------------------------

Reference:

Goldberg, Pinelopi, Amit Khandelwal, Nina Pavcnik, and Petia Topalova (2010). "Imported Intermediate Inputs and Domestic Product Growth: Evidence from India," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125 (4), 1727-1767.

Johnson, Robert and Guillermo Noguera (2014). "A Portrait of Trade in Value Added over Four Decades." Dartmouth College Working Paper.

Kee, Hiau Looi (2015). "Local intermediate inputs and the shared supplier spillovers of foreign direct investment." Journal of Development Economics, 112, 56-71.

Kee, Hiau Looi and Heiwai Tang (forthcoming). "Domestic Value Added in Exports: Theory and Firm Evidence from China" American Economic Review. Also available as World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS 7491.

Figure 1: Value Added to Gross Export (VAX) Ratios Across the World

Source: Johnson and Noguera (2014)

In a recent Bank study based on firms and customs transaction level data, Kee and Tang shows that China is an intriguing exception to the global decline depicted in Figure 1, despite its deep engagement in global value chains. The share of domestic content in Chinese exports has risen from 65% in 2000 to 70% in 2007 (see Figure 2). The increase is even sharper for the processing sector, which has the share of domestic content improved from 46% in 2000 to 55% in 2007. The study also finds that the increase in the domestic value added in Chinese exports is mainly driven by individual processing exporters substituting domestic for imported materials, both in terms of volume and varieties. Other factors, such as rising wages, changing composition of Chinese exports towards the high-DVAR industries or the non-processing sector, or firm entry and exit, cannot explain the upward trend during the period of the study. This evidence is consistent with China moving-up the GVC with a more sophisticated domestic intermediate product sector supporting the downstream processing export sector.

Figure 2: Domestic Value Added in Exports for China (2000-2007)

Source: Kee and Tang (forthcoming)

How has China moved up the GVC? Detailed firm-level analysis by Kee and Tang (forthcoming) suggests that this is accomplished through a structural transformation fused by trade and FDI liberalization of China since 2000. Such liberalization encouraged intermediate input producers in China to expand their product varieties, similar to what has been found in India by Goldberg et al. (2010), and in Bangladesh by Kee (2015). As such, exporters in China buy more domestic intermediate inputs and rely less on imports. Overall, trade and FDI liberalization can explain a bulk part of the increase in domestic value added in Chinese exports.

For policymakers interested in promoting domestic value added in exports, the findings of this study suggest that conducive trade and FDI policies are very important. Particularly, the study provides empirical support for the idea that designing policies to attract FDI with significant backward linkages may help promote intermediate input industries while also benefitting domestic final goods firms and raising their domestic value added.

For a related column, please refer to http://www.voxeu.org/article/china-and-global-value-chain-new-evidence. Also available as World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (WPS 7491).

-------------------------------

Reference:

Goldberg, Pinelopi, Amit Khandelwal, Nina Pavcnik, and Petia Topalova (2010). "Imported Intermediate Inputs and Domestic Product Growth: Evidence from India," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125 (4), 1727-1767.

Johnson, Robert and Guillermo Noguera (2014). "A Portrait of Trade in Value Added over Four Decades." Dartmouth College Working Paper.

Kee, Hiau Looi (2015). "Local intermediate inputs and the shared supplier spillovers of foreign direct investment." Journal of Development Economics, 112, 56-71.

Kee, Hiau Looi and Heiwai Tang (forthcoming). "Domestic Value Added in Exports: Theory and Firm Evidence from China" American Economic Review. Also available as World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS 7491.

Join the Conversation