Growth in emerging economies has slowed over the past three years, something being discussed with urgency at the G20 meetings in Istanbul, Turkey. Part of the slowdown is cyclical, but a significant part reflects sluggish potential growth. Using new empirical evidence, this column argues that ambitious structural reforms can fully

offset the slowdown of potential growth in emerging economies. Reforms that remove barriers to open markets and improve access to finance play a key role in revitalizing total factor productivity growth and boosting private investment.

The period preceding the 2008-09 global financial crisis saw remarkable growth and poverty reduction in developing countries. However, after an impressive recovery in 2010, growth has been slowing steadily in emerging economies, including in China, India, and Brazil. In developing countries as a whole, per capita GDP grew by 4.6 percent per year over 2010-2013, about 2 percentage points slower than in the pre-crisis period.

The growth slowdown in emerging economies raises two main concerns: First, the slowdown may reflect exposure to the so-called “middle-income trap”, a phenomenon that entails risks of stagnation at middle-income levels and a failure to “graduate” into the advanced economy group. Second, there is concern that the post-crisis sluggish growth in advanced economies may continue, due to the fragilities in banking systems, the high levels of debt, high structural unemployment, and other structural bottlenecks. This could compound the risks of a structural growth slowdown as many countries that relied on fast growing export markets and favorable terms of trade would not be able to count on the same degree of external demand stimulus.

Post-crisis performance and the significance of structural bottlenecks to growth

In a recent paper), we assess the extent to which structural bottlenecks have impeded the growth of emerging economies in the post-crisis period and whether these bottlenecks can be removed through appropriate structural reforms. We attempt a more granular investigation of structural bottlenecks compared to previous studies, by using indicators that measure barriers to open markets (reflected in barriers to trade, foreign direct investment, and competition); barriers to business operations; and ease of access to finance.

The empirical research is based on the construction of indexes of structural bottlenecks for 30 upper middle-income emerging economies, including all emerging economy members of the G20. These indexes encompass indicators from the World Bank’s Cost of Doing Business database and from the World Economic Forum’s Global Competiveness Report.

We focus on the performance of total factor productivity (TFP) growth and private investment as a proportion of GDP. Both are key determinants of potential growth and reflect the capacity of an economy to promote structural transformation and allocate resources to higher productivity and value-added sectors. We compare post-crisis trends in TFP growth and private investment, measured over the period 2010-12, to the pre-crisis period 2003-07. In the vast majority of the countries in the sample, TFP growth post-crisis was sluggish compared to the pre-crisis period. By contrast, post-crisis private investment as a proportion of GDP has been significantly more resilient.

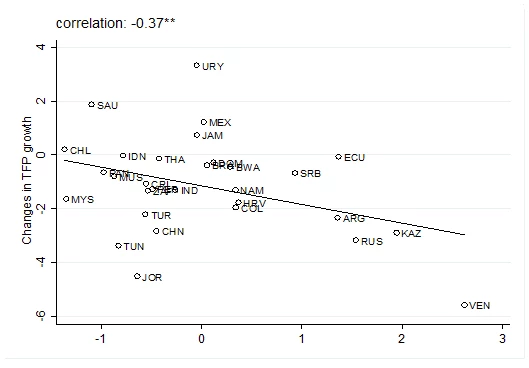

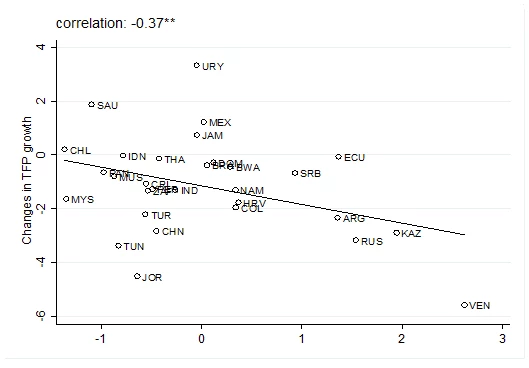

There is evidence that post-crisis TFP growth and private investment were stronger in emerging economies with lower structural bottlenecks to growth as measured by the three composite indexes presented above. This is confirmed by regressions of the difference between each country’s TFP growth in 2010-12 and 2003-07 on the country’s average score on each of the three aggregate indexes of structural bottlenecks to growth. Similar regressions were estimated for post- and pre-crisis differences in private investment as a proportion of GDP.

We find that:

Figure 1: Correlations between changes in TFP growth (2010-2012 vs. 2003-2007) and indexes of structural bottlenecks

Ease of Access to Finance

Barriers to Open Markets

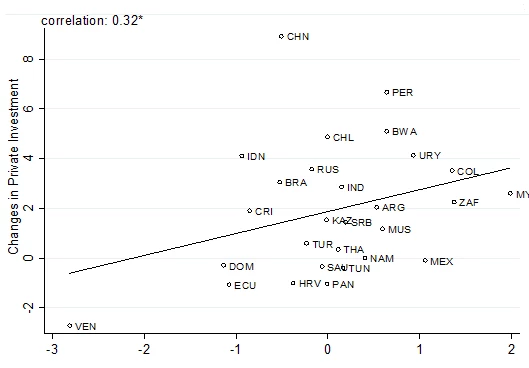

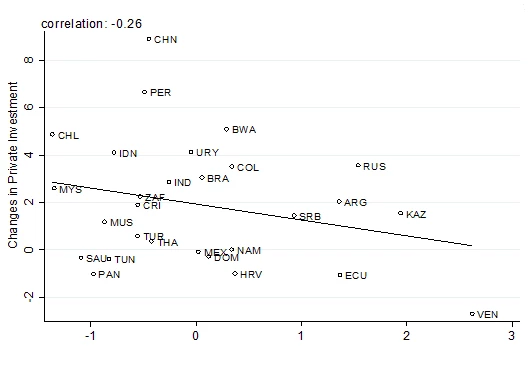

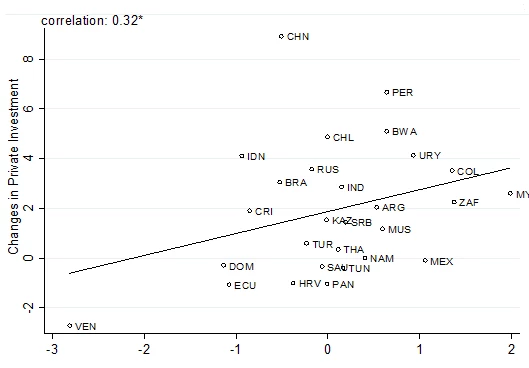

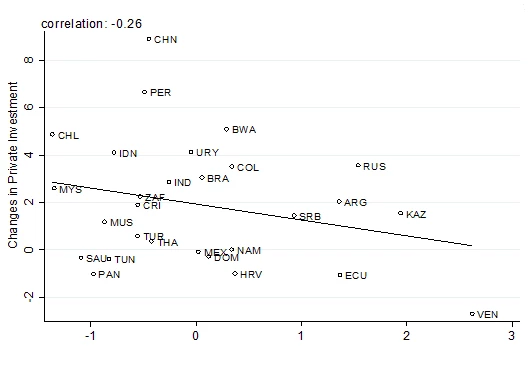

Figure 2: Correlation between changes in Private Investment (2010-2012 vs. 2003-2007) and indexes of structural bottlenecks

The period preceding the 2008-09 global financial crisis saw remarkable growth and poverty reduction in developing countries. However, after an impressive recovery in 2010, growth has been slowing steadily in emerging economies, including in China, India, and Brazil. In developing countries as a whole, per capita GDP grew by 4.6 percent per year over 2010-2013, about 2 percentage points slower than in the pre-crisis period.

The growth slowdown in emerging economies raises two main concerns: First, the slowdown may reflect exposure to the so-called “middle-income trap”, a phenomenon that entails risks of stagnation at middle-income levels and a failure to “graduate” into the advanced economy group. Second, there is concern that the post-crisis sluggish growth in advanced economies may continue, due to the fragilities in banking systems, the high levels of debt, high structural unemployment, and other structural bottlenecks. This could compound the risks of a structural growth slowdown as many countries that relied on fast growing export markets and favorable terms of trade would not be able to count on the same degree of external demand stimulus.

Post-crisis performance and the significance of structural bottlenecks to growth

In a recent paper), we assess the extent to which structural bottlenecks have impeded the growth of emerging economies in the post-crisis period and whether these bottlenecks can be removed through appropriate structural reforms. We attempt a more granular investigation of structural bottlenecks compared to previous studies, by using indicators that measure barriers to open markets (reflected in barriers to trade, foreign direct investment, and competition); barriers to business operations; and ease of access to finance.

The empirical research is based on the construction of indexes of structural bottlenecks for 30 upper middle-income emerging economies, including all emerging economy members of the G20. These indexes encompass indicators from the World Bank’s Cost of Doing Business database and from the World Economic Forum’s Global Competiveness Report.

We focus on the performance of total factor productivity (TFP) growth and private investment as a proportion of GDP. Both are key determinants of potential growth and reflect the capacity of an economy to promote structural transformation and allocate resources to higher productivity and value-added sectors. We compare post-crisis trends in TFP growth and private investment, measured over the period 2010-12, to the pre-crisis period 2003-07. In the vast majority of the countries in the sample, TFP growth post-crisis was sluggish compared to the pre-crisis period. By contrast, post-crisis private investment as a proportion of GDP has been significantly more resilient.

There is evidence that post-crisis TFP growth and private investment were stronger in emerging economies with lower structural bottlenecks to growth as measured by the three composite indexes presented above. This is confirmed by regressions of the difference between each country’s TFP growth in 2010-12 and 2003-07 on the country’s average score on each of the three aggregate indexes of structural bottlenecks to growth. Similar regressions were estimated for post- and pre-crisis differences in private investment as a proportion of GDP.

We find that:

- Better access to finance, lower barriers to open markets, and lower barriers to business operations are all associated with higher TFP growth post-crisis compared to pre-crisis levels, although the effect of barriers to operations is not statistically significant.

- Better access to finance has a significant positive effect on private investment changes. Lower barriers to open markets are associated with higher private investment post-crisis but the effect is not statistically significant. Lower barriers to business operations have an opposite than expected impact but are not statistically significant.

Figure 1: Correlations between changes in TFP growth (2010-2012 vs. 2003-2007) and indexes of structural bottlenecks

Ease of Access to Finance

Barriers to Open Markets

Figure 2: Correlation between changes in Private Investment (2010-2012 vs. 2003-2007) and indexes of structural bottlenecks

Ease of Access to Finance

Barriers to Open Markets

The robust results on the impact of barriers to open markets on TFP growth post-crisis are worth emphasizing. Progress in reducing these barriers has been slow; indeed these barriers have even increased in several emerging economies. Practically all G20 members have resorted to trade distorting measures since the onset of the crisis, some more than others. In the post-crisis period, several G20 emerging economies have raised barriers to trade and FDI. A more ambitious reform agenda in this area can contribute to faster potential growth by boosting TFP growth.

The findings suggest that improving the policy framework in the areas of ease of access to finance and market openness, by bringing it up to the level of the best-ranking emerging economies, could help offset the structural part of the growth slowdown in the emerging economies in the post-crisis period. Indeed, based on the estimated results, structural reforms that improve country scores in these two areas so as to bridge the difference between the three best ranking G20 emerging economies (Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa) and the three lowest ranking ones (Argentina, Brazil, Russia) could boost TFP growth sufficiently to fully offset the slowdown in the post-crisis period. Moreover, this same improvement in scores would boost private investment, further stimulating GDP growth and spurring job creation in emerging economies.

Barriers to Open Markets

The robust results on the impact of barriers to open markets on TFP growth post-crisis are worth emphasizing. Progress in reducing these barriers has been slow; indeed these barriers have even increased in several emerging economies. Practically all G20 members have resorted to trade distorting measures since the onset of the crisis, some more than others. In the post-crisis period, several G20 emerging economies have raised barriers to trade and FDI. A more ambitious reform agenda in this area can contribute to faster potential growth by boosting TFP growth.

The findings suggest that improving the policy framework in the areas of ease of access to finance and market openness, by bringing it up to the level of the best-ranking emerging economies, could help offset the structural part of the growth slowdown in the emerging economies in the post-crisis period. Indeed, based on the estimated results, structural reforms that improve country scores in these two areas so as to bridge the difference between the three best ranking G20 emerging economies (Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa) and the three lowest ranking ones (Argentina, Brazil, Russia) could boost TFP growth sufficiently to fully offset the slowdown in the post-crisis period. Moreover, this same improvement in scores would boost private investment, further stimulating GDP growth and spurring job creation in emerging economies.

Join the Conversation