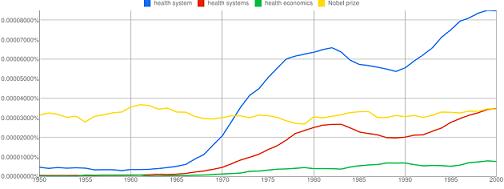

In 1960, I wouldn’t have been writing this blog post. For a start I was just a baby at the time. Second, we were several decades away from 1994 when Justin Hall – then a student at Swarthmore – would sit down and tap out the world’s first blog. Most importantly of all, though, according to Google’s ngram viewer, people didn’t write about health systems much in 1960 (see chart). Usage of the term in books took off only in the mid 1960s, waned in the 1980s, and then started rising again in the 1990s. This doesn’t look like a statistical artifact. Usage of the term “Nobel prize” has stayed relatively constant over the period, and while the term “health economics” has also trended upwards, the growth has been much slower. So “health systems” is a fairly new term – and it’s on the rise.

Not everyone thinks that’s a good thing.

In a recent blog post (available on the World Bank’s intranet only), Caroline Anstey, a Bank managing director, asked whether we aren’t risking alienating non-specialists by using a language that might seem more at home in a mechanical engineering course. Aren’t health systems about people, she asked? Doesn’t the language of health systems obscure that? And doesn’t our use of highfalutin terms like “systems” make the issues involved seem more complex than they really are?

I think she’s right on the people question. In fact, I think she understates the degree to which we fail to acknowledge the human dimension to health systems. But I’m less sure we’re overstating the complexity of the health systems agenda. In fact, by missing out the human dimension, I think we’re at risk of making the health systems agenda appear simpler than it really is.

Human problems. Engineering solutions

We health systems aficionados typically do well in getting across the idea that the goals of a health system are people-oriented. We want health systems to improve health – to stop babies dying before they reach their first birthday; to stop mothers dying in childbirth; to stop children and adults contracting and dying from diseases that can be prevented and treated. We also want them to protect families from the potentially impoverishing effects of illness, disease and injury – making sure that families can afford the medical care that can help the affected family member get better, and get back to work. The World Health Organization would like to add a third goal to the list – make sure patients are treated with respect by health providers. We can quibble over whether the last is really a goal, but what we can agree is that all three goals are about improving people’s lives. They’re not about fixing the performance of some inanimate object in an engineering system. We’re talking about life and death of human beings, about reducing their suffering, and about improving their livelihoods. It’s hard to get more people-oriented than that!

It’s where we start talking about the means to achieving these ends we rather lose sight of the people dimension. And it’s here we start underestimating the complexity of the health systems agenda.

Too often we have presented solutions in technical terms. We list the health problems people are suffering from, and calculate the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost. We list the medical and other interventions available to address these diseases and conditions, and present charts showing how death rates could be slashed if only these interventions were fully used. In so doing, we give the impression the solution is a technical one – we omit to mention that interventions cannot be dropped like manna from heaven. Much of the 1993 WDR came across in this vein. That helps explain why it went down less well with economists than it did with a certain very successful software engineer, who on reading it promptly decided to give up his day job to start a foundation dedicated in part to fighting disease in the developing world.

Even when we acknowledge that a health system is needed to deliver interventions, we still tend to present the problem as a technical one. We talk about the need to have a cold chain system in place to make sure vaccines are available in clinics. We talk about the need to have clinics in the first place, and to make sure they’re properly furbished and equipped. And so on.

When we talk about the human inputs into health systems – doctors and other health workers – we often discuss them using a language that suggests we think of them as little more than robots. We talk about the need to ensure that rural clinics are properly staffed; solution – send urban providers to work in rural areas for a while, and discourage emigration of health workers from the South to the North. We talk about the need to ensure that health workers are properly trained; solution – train them. And so on.

Human problems require human solutions

What we miss in our discussion of the human dimension of health systems is that the people needing medical care and the people delivering them are – at the end of the day – people, like you and me.

Just as we often miss the point that families may deliberately choose not to send their children to school (see Berk Ozler’s recent blog post), we also miss the point that families won’t necessarily take a sick family member to a clinic. They need to be able to afford it – in terms of money and time. They need to have confidence in the health care providers who work in the clinic, and need to think it likely that the necessary medicines will be in stock. Many sick people don’t jump all these hurdles, and simply don’t seek care. Or if they do, they may go to an untrained provider or a drug peddler instead of a formal provider.

By the same token, we can’t blithely assume that because they have been assigned to a health post, doctors and other health workers will necessarily be there. One of the first-ever absenteeism surveys – done in Bangladesh on a representative national sample of health centers – found 74 percent of doctors posted to the smallest rural clinics were absent at any given time. A subsequent six-country study found absenteeism rates averaging 35 percent among medical workers in the six countries, with much higher rates in some Indian states.

Even when health providers are present in their facility, we have no assurance that they will deliver high-quality care. In fact, the evidence suggests otherwise. In part this is because they lack the core knowledge. In Delhi, for example, on hypothetical tests the most competent 20 percent of doctors asked or did only about 30 percent of the essential questions / tasks in a “vignette” about diarrhea treatment for young children. But it’s not just that providers lack the relevant knowledge. It’s also that in practice they only do a fraction of the things they know they should do. In India, where this research is most advanced, this “know-do” gap varies by provider type, and can be huge. In Delhi, unqualified doctors do all the essential tasks they know about, but they know only 20 percent of the essential tasks. Qualified private doctors know 40 percent of essential tasks but do only 25 percent of them. By contrast, public-sector doctors know 30 percent of essential tasks but do only 8 percent!

Incentivizing providers to deliver care can help. In Rwanda, when clinics were rewarded financially for delivering specific items of care, the volume of care provided increased. But it’s easy to make financial incentives too strong, and to divert providers away from doing the things we’d like them to be doing. In China, the government made certain HIV/AIDS tests and interventions free of charge, but omitted to reimburse hospitals from delivering them. Unsurprisingly, as the Washington Post reported, hospitals responded by giving patients tests and interventions that they could charge for, and only when the patients had no money left went on to give them the free tests and interventions.

We also need to understand the non-financial factors that motivate health providers. In Andhra Pradesh, income was just one of several factors found to motivate health workers in both public and private sectors – as important were training opportunities, challenging work, good working conditions, and a good working relationship with colleagues.

Less engineering. More social science

So, yes, I agree we need to humanize the health systems agenda. That means in part clarifying the people-centeredness of health system goals.

But it means more than that. We have to work harder to understand the motivations and behaviors of the two key groups of ‘actors’ in any health system – the people who we’re trying to get health care to, and the people who are delivering the care. We need to understand why prospective patients and providers behave the way they do, and nudge them or incentivize them into behaving differently. That’s not an agenda that engineers – or even doctors – can easily relate to. It’s fundamentally a social science agenda, and a complex one at that. Why don’t doctors show up to work? Why don’t they improve their skills, and make better use of them during a contact with a patient? These are questions that cry out for a social scientific analysis, probably a mix of microeconomics and psychology. The language of ‘systems’, with its connotation of engineered solutions, may well get in the way. It not only puts off potential allies to the health systems ‘cause’. It also sets us off searching for technical solutions to problems that are fundamentally about human behavior.

Join the Conversation