Last month, the World Bank and IMF both put out predictions that, this year, India would overtake China in terms of GDP growth rate. This caused a flutter and was widely reported around the world. How robust is this prediction and what does it really mean?

First, this is not as monumental a milestone as some commentators made it out to be. China has had one of the most remarkable growth runs witnessed in human history, having exceeded an annual growth of 9% from 1980 to now. Four decades ago its per capita income was close to India’s, but now it is four times as large as India’s. None of all this is going to change in a hurry.

With this caveat in mind, it is a year in which India deserves to feel good. It is expected to top the World Bank’s chart of growth rates in major nations of the world. This has never happened before. Before 1990, India did occasionally grow faster than China, mainly because China’s growth gyrated wildly during the pre-Deng Xiaoping period. It was, for instance, minus 27% in 1961, when Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward resulted in the world’s biggest famine, and it was 17% and 19% in 1969 and 1970, respectively--a relief in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. Fluctuations of this magnitude would be intolerable to India’s polity.

Since 1980, China has grown rapidly without interruption. Since 1990, its growth has continuously surpassed India’s. Hence, the World Bank’s forecast of India growing faster than China this year is a once in a quarter century occasion.

The resulting high expectations for India lie not in the GDP growth crossover (which is not as significant as some make it out to be), but in the dynamics underlying the country’s aggregate numbers.

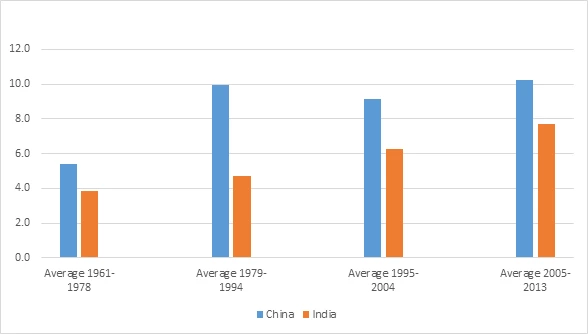

An initial dynamic to consider relates to the steadiness with which growth in India climbed over the past five decades. The accompanying bar chart makes this clear. The chart breaks up the last half century into four periods: from 1961 to the arrival of Deng Xiaoping at the helm of China; from 1979 to India’s reforms of the early 90s; from 1994 to the start of a growth spurt in India in 2005; and from 2005 to recent times. Over these four periods, India’s growth has increased steadily. Annual growth was 3.9% from 1961-78; 4.7% 1979-94; 6.2% 1995-2004; and 7.7% 2005-2013. And within the latter segment, there was a remarkable sprint from 2005 to 2008 when India grew annually by over 9%.

All this is also borne out by India’s GDP. The last two rounds of purchasing power parity (PPP) computation for the world occurred in 2005 and 2011. It turns out that in terms of PPP-adjusted GDP, India overtook Japan and Germany between 2005 and 2011, and stood behind only the US and China. (Note: As of October 2014, China’s PPP-adjusted GDP has overtaken that of the US).

The expected growth of 7.5% this year is worse than India’s performance in many past years, but it is quite remarkable given today’s subdued global prospects.

Growth in China and India

A second dynamic relates to several important policy initiatives laid out in the Union Budget presented in February 2015. The most important is the Goods and Services Tax (GST), which will create a unified national taxation system, cutting down transactions costs for businesses and the movement of goods. Data collected by the World Bank show that, when Indian trucks carry freight between cities, 60% of the time is spent stationary, mainly at check points to pay taxes and get permits. The GST can cut down this colossal wastage. Indeed, India’s biggest stumbling block has been its large transactions and bureaucratic costs. Several reforms at the time of the last Union Budget raise hopes that these costs will be curtailed, and optimism is a powerful driver of growth.

Third, the fall in oil prices since June 2014 has turned out to be a boon for oil-importing India. The high cost of oil has caused India’s current account deficit to be large and created a heavy fiscal drag for decades. This has eased greatly over the past 9 months and the Bank’s projections suggest that oil prices will be low — somewhere between 55 and 70 dollars—over the medium term. This is a great opportunity for India to reform, deploy resulting savings to boost spending on health and education, and promote shared prosperity.

Finally, democracy presents an interesting dynamic for India. On the one hand, it can be a drag and often is. A democracy like India’s makes it difficult to experiment with new policies and to make policy switches of the kind China could make easily and even Korea made in the 1970s. On the other, it does provide a stability and basis for sustained development. India is fortunate that, through the rough and tumble of economic life, it has managed to hold on to democratic traditions and a vibrant media. I remember in my last job, every time I stepped out of the Ministry of Finance in Delhi after an important meeting, there would be dozens of journalists accosting me with aggressive questions, and, though that would often put me in a spot, there was something energizing about this, and, in the long run, this is a strength that should stand the country in good stead.

Join the Conversation