Can government policies designed to promote financial inclusion encourage people to open an account at a bank or other financial institution?

Results from our paper using a new survey of 13,000 adults across India suggest they can have an impact. Women, poor and illiterate adults were more likely to apply for an account after the government-led Jan Dhan Yojana (JDY) program was introduced in India to encourage account ownership.

The survey was carried out in early 2016, roughly a year and a half after the Indian government launched its flagship JDY program to achieve universal account ownership. The program encouraged every household to open one account by offering zero-balance accounts with no opening fees.

The JDY has yielded impressive results: At the end of 2016, about 250 million accounts had been opened thanks to the new policy—earning the Indian government a Guinness World Records certificate recognizing the feat.

We asked respondents if they had ever applied for an account at any financial institution. We found that 68 percent of adults in surveyed states had applied for an account at some point in their lives.

Among this group, one third – or 21 percent of adults – had applied for a JDY account.

The most interesting finding: In the 12 months preceding the survey, groups that traditionally didn’t have accounts applied in greater numbers than those that would otherwise fare better with traditional accounts.

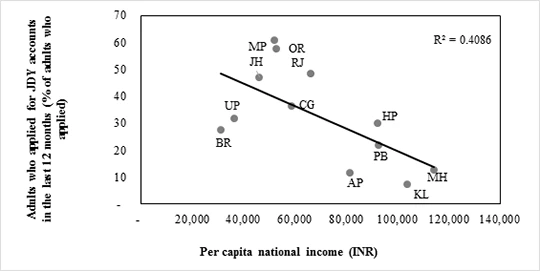

In other words, we found JDY application rates were negatively correlated with wealth at the state level. That suggests the policy disproportionally helped adults in poorer states (Figure 1). The findings ran counter to traditional application rates, whereby wealthier people are more likely to apply for an account

Figure 1: Account applications for JDY accounts and state-level national income per capita

Adults who applied for an account (%)

In our survey, women and the poor were significantly more likely – 5 percentage points – to apply for JDY accounts than men and wealthier adults. Application rates were 10 percentage points higher among illiterate adults compared with those who had studied beyond primary school. Moreover, single adults were more likely to apply for an account than married adults – by a 7-percentage-point gap.

What factors were at work?

-

JDY policy made documentation requirements lenient –a 12-digit Aadhaar biometric ID number, issued to almost a billion adults in India, would suffice.

-

The program also made access to bank branches significantly easier through micro-ATMs and pop-up branches.

Only 8 percent of adults who applied for a JDY account said travelling to the bank was expensive in terms of money spent on transportation versus 18 percent of adults who applied for a traditional account.

Figure 2: Efficiency of applying for JDY and traditional accounts, by application step: Percentage of applicants who reported the following steps as difficult or expensive

Adults who applied in the last 12 months (%)

Enticing as it sounds, we also found that launching such a scheme does not come without challenges.

While a whopping 70 percent of applicants cited receiving, sending and saving money as their main reason for applying for an account, 13 percent applied because they expected the government to hand them a cash bonus for opening a JDY account.

While some accounts will be used to receive future government transfer payments, the false expectation of free money could leave many people with accounts that are not used.

Even adults who ended up applying faced a host of other challenges. More than half of JDY applicants reported paying a required minimum initial deposit, even though the program carries no such requirement. It’s understandable that banks need deposits to make accounts commercially viable. But such a minimum deposit violates the intent of the government’s program.

In addition, 18 percent of adults had to offer a bank agent a bribe in the form of a gift or money to open their account. This points to the need for better governance of bank agents and NGOs assisting with the vast task of bringing hundreds of millions of adults into the formal financial system. While correspondent agents are a key tool to connect rural residents and poor adults with formal financial institutions, trust in the integrity of these agents is critical for the JDY program to succeed.

Our results point to the importance of clarifying and simplifying JDY account opening procedures.

They also reveal opportunities for India to build on its financial inclusion successes. Initiatives such as Payment banks—which can’t advance loans or issue credit cards, but can offer remittance services, mobile payments/transfers and other banking services like ATM/debit cards, are promising steps towards improving travel time and transportation costs for poor and rural residents by allowing them to access financial services through mobile phones.

While financial inclusion begins with having an account, the benefits only come from active use of that account to make payments, save money and manage risk. Ultimately, financial inclusion schemes should build on that goal.

To read the full working paper, click here.

Join the Conversation