Ceilings on lending rates remain a widely-used instrument in many EMDEs as well as developed economies. The economic and political rationale for putting ceilings on lending rates is to protect consumers from usury or to make credit cheaper and more accessible. Our recent working paper shows that at least 76 countries around the world, representing more than 80% of global GDP and global financial assets, impose some restrictions on lending rates. These countries are not clustered in specific regions or income groups, but spread across all geographic and income dimensions.

Interest rate caps are not static, but are an actively used policy tool. Since 2011, we find at least 30 instances when either new interest rate caps have been introduced or existing restrictions have been tightened. Over 75% of those changes occurred in low- or lower-middle-income countries. This outweighs the five instances when restrictions have been removed or eased and indicates that countries increasingly limit the maximum level of lending rates.

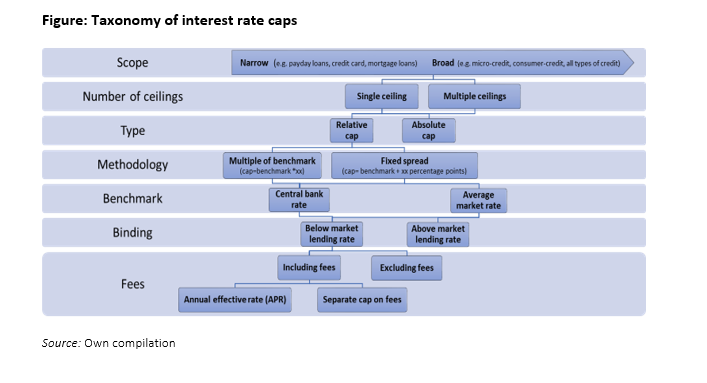

A taxonomy of interest rate caps

Interest rate caps come in many different forms. Restrictions used across countries vary substantially regarding what they cover and how they work. A innovative taxonomy presented in this paper classifies interest rate caps according to the following features:

- Scope. A primary form of variation is the type of credit instrument/ institution and/or borrower they apply to. Caps can affect only a narrowly defined segment of the market (e.g. payday loans, credit cards, mortgages), cover loans by certain institutions (e.g. MFIs or credit unions) or cover all types of credit operations in the economy.

- Number of ceilings. Countries use either a single blanket cap for all transactions or multiple caps based on the type of the loan and/or socio-economic characteristics of the borrower.

- Type. The level of the cap can be either defined as a fixed, absolute cap or as a relative cap that varies based on the level of a benchmark interest rate.

- Methodology. The level of the relative cap can be either defined as a fixed spread over the benchmark or as a multiple of the benchmark rate.

- Benchmark. Most countries using a relative cap link it to the level of an average market rate, for example, the average lending rate over the past six-months. Alternatively, the ceiling can be defined as a function of the central bank’s policy rate.

- Binding. Independently of the type of benchmark used, caps can be binding or non-binding, i.e. they are below or above market rates. In countries where the primary aim is to prevent usury the ceilings are usually fixed at levels that affect only extreme pricing but leave the core market to operate with minimal implications. In contrast, if interest rate caps are used as a policy tool to achieve certain socio-economic goals, such as lower overall cost of credit, ceilings are set at binding levels intended to influence the market outcome.

- Fees. Some interest rate caps also explicitly regulate non-interest fees and commissions of the loan. This is either done by setting separate limits on non-interest costs or by defining the interest cap in terms of an annual effective rate (APR) that includes all fees and charges.

Effects of interest rate caps

Establishing the causal effects of interest rate caps is challenging due to the heterogeneity of caps used and endogeneity concerns, but economic theory points to several possible side effects. Country case studies on Kenya, Zambia, Cambodia, the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), India, and the United Kingdom show that effects and side-effects depend on the type and specification of the cap.

- Caps set at high levels do not seem to affect the market and can help limit predatory practices by formal lenders. Non-binding caps, i.e. caps set well above market rates, affect only extreme pricing with little impact on the overall market. If interest rate caps include regulations on non-interest fees and the non-regulated lending market is limited, then caps are a potential way to remove predatory lenders in the formal sector.

- The effectiveness of caps is often undercut by the use of non-interest fees and commissions. The increased use of non-interest charges often reduces price transparency and makes it more complicated for borrowers, especially those with limited financial literacy, to assess the overall costs of the loan.

- Binding caps set well below market levels can reduce overall credit supply. The extent of the decline depends on the scope of the restrictions. Whereas narrow caps affect primarily a clearly defined market segment, broad restrictions can reduce overall credit supply in the economy. Blanket caps further affect the distribution of credit as they result in a particularly large decline of unsecured and small loans, as well as in credit to SMEs and riskier sectors. Average loan size increases, suggesting a reallocation from small to large borrowers, in many cases to the government.

Join the Conversation