“Sunlight is the best disinfectant” is an often-heard recommendation for preventing bribery in government. We now have evidence that transparency regulation does in fact check bribery in public procurement. Doing something as simple as publishing bidding documentation online – where it can be seen by anyone -- is associated with a reduced incidence of giving money or favors to secure government contracts.

Can it be that simple? The data suggest the answer is yes. In ongoing research with professors Edward Glaeser and Andrei Shleifer at Harvard, we recorded transparency regulations in 187 countries. These ranged from requirements to publish documents online to rules mandating online posting of winning bids and explanations of why other bids were not chosen. The regulations governed government procurement of goods, services and works from the private sector.

At 12 percent of global GDP and an estimated value of $11 trillion, public procurement is huge business. Private companies are required by law to follow a number of procedures to ensure efficient delivery of whatever the government needs in a timely manner. Yet with so much at stake, it is easy to see why a contractor might be tempted to offer a bribe to win a lucrative public contract.

Here is where the sunlight of transparency regulations becomes invaluable. These rules mandate the publication of procurement plans, model procurement documents, tender notices, tender documents, technical specifications, notices of award and bidding results, contracts and contract amendments.

Unfortunately, few countries require the publication of all such documents by law. (Peru is an exception.) While almost every country requires tender notices to be made publicly available, only 22 countries require procuring entities to publish contracts with selected bidders, even allowing for redaction as needed. In almost a third of the sample – 52 countries – procuring entities are not legally required to publish a notice of award that lists the winner of the bidding process. (Lebanon and Myanmar are among those who do.)

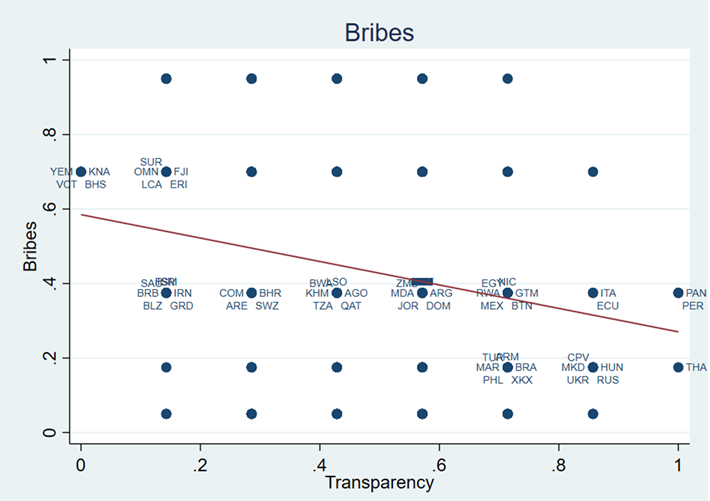

In our work, we aggregate these regulations into a single equally-weighted index and relate them to a measure of bribe-taking (figure 1). The correlation is clear: more transparency, less incidence of bribery.

Figure 1 – Transparency in procurement reduces the incidence of bribes

Source: Doing Business database.

Compliance with transparency regulation comes at little cost. It does not take much effort to post online the documentation generated during the public procurement process. The payoff in terms of reduced expenses seems large – up to a quarter of a project’s value – which is why countries as diverse as France, Russia, Thailand and Peru have reformed their regulations to increase transparency in public procurement.

Why are politicians in other countries not jumping at the opportunity to save public money by reducing bribery? One is reminded of a satire made famous by the 19th century French economist Frédéric Bastiat. In a petition to Parliament in 1845, French candlemakers asked that the sun be blocked to protect their interests. “We are suffering from the ruinous competition of a rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price; ....This rival is none other than the sun,” they complained.

For some procurement entities, hiding the sun and veiling the procurement process may appear to be a clever way to retain their influence. However, this comes at the expense of an efficient procurement process that is needed to support development priorities effectively. Sunlight removes opportunities for uncompetitive bidders to win public contracts. This should be seen as a credit to those who manage the procurement of public works and a benefit for all.

Join the Conversation