Family celebrating graduation outdoor.

Family celebrating graduation outdoor.

In the 1950s, Simon Kuznets hypothesized that an inverted U-shaped relationship exists between inequality and development. As countries developed, inequality would increase until a certain tipping point, after which it would start to fall again. Although this hypothesis is highly contested, the inverted U-curve is featured in most introductory textbooks on development economics.

A new working paper presenting the Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility makes it possible for the first time to study the relationship between economic development and intergenerational mobility across a wide cross-section of countries that includes both the world’s poorest and richest countries. Intergenerational mobility is related to but different from inequality. Where inequality in Kuznets’ theory describes the dispersion of incomes, intergenerational mobility is related to the dispersion of opportunities. We distinguish between two different concepts of intergenerational mobility, which we refer to as absolute and relative. Absolute mobility measures whether children are doing better than their parents, while relative mobility measures how strong the connection is between parents’ outcomes and children’s outcomes.

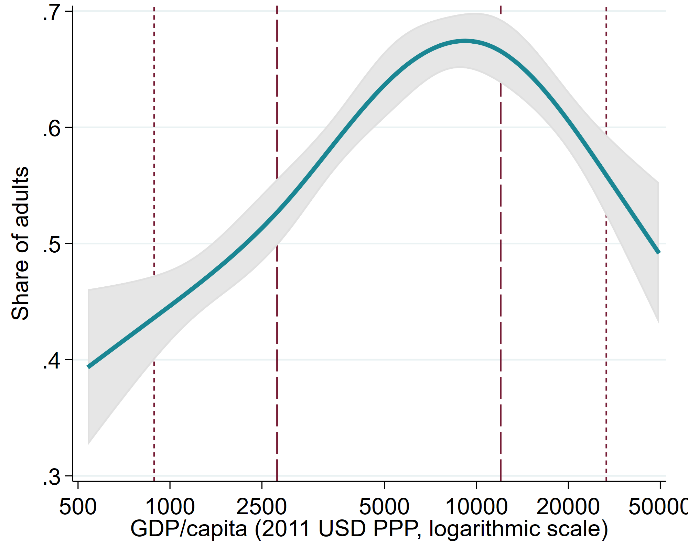

To achieve a truly global coverage of 153 countries representing 97 percent of the world’s population, the Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility focuses on intergenerational mobility in education. Our measure of absolute mobility in education is the share of individuals who have attained more years of schooling than their parents. The measure of relative mobility in education presented here is (one minus) the correlation between a cohort’s years of schooling and their parents’ years of schooling. Higher the correlation, the more parents’ education is predictive of their children’s education success, and lower the relative mobility. Plotting these measures of intergenerational mobility against GDP per capita around the time when children entered school allows for testing Kuznets’ hypothesis in the domain of socio-economic mobility.

The results are strikingly clear.

| Intergenerational mobility vs. GDP per capita |

|

| Absolute mobility Share of adults with more years of schooling than their parents |

Relative mobility One minus the correlation between the years of schooling of adults and their parents |

|

|

|

| Note: The dashed lines indicate the 25th and 75th percentile of the distribution of GDP per capita. The dotted lines indicate the 5th and 95th percentile. |

|

An inverted U-shaped relationship exists between absolute mobility and development while the relationship between relative mobility and development shows a regular U-shape. The slope changes sign at around $10,000 for absolute mobility and around $5,000 for relative mobility (in 2011 USD PPP). Both of these thresholds correspond to income levels of middle-income countries. This predicts that countries with very different levels of national income may achieve similar levels of intergenerational mobility. For example, the Dominican Republic and Japan are estimated to have the same level of absolute mobility (around 0.55). Similarly, Liberia and Israel are estimated to have the same level of relative mobility (around 0.6).

Before commenting on a possible rationale for these patterns, one methodological sidestep is necessary. A challenge with measuring intergenerational mobility in education is that education in bounded both from the bottom and the top. This may matter for both measures.

In terms of absolute mobility, if parents have a university degree, it is difficult to outperform them. As a country gets wealthier, more people complete tertiary education, and it becomes harder for children to outperform their parents. This would imply a mechanical decline in absolute mobility at high levels of development. One pragmatic way of getting around this is to categorize children of parents with tertiary education as upwards mobile if they match their parent’s tertiary education. In the paper we show that even with this adjustment, absolute mobility continues to decline at very high levels of GDP per capita.

The boundedness of education attainment might also matter for relative mobility. This is particularly pertinent for low levels of development, where a large fraction of the population has zero years of schooling. As we will argue below, in these cases, it is not altogether clear how to think about relative mobility. A completely different measure of relative mobility which is less impacted by what happens in the bottom of the distribution is the probability that a child born in the top quartile falls out of the top quartile. The U-curve is also present with this measure.

So what can explain these patterns?

With regards to the inverted U-shape between absolute mobility and development, the intuition may be reminiscent of Kuznets’ original intuition. At low levels of development, a country is stuck in poverty and though the threshold for surpassing parents’ education is low, so is the capacity to educate children. As countries start to grow, individuals start doing better than their parents. Sooner or later, growth rates start to level off, and a smaller fraction improves upon the past generation. Though the capacity to educate children is high so is the threshold for surpassing parents’ education levels.

A candidate explanation for the observed pattern for relative mobility is the following. In the world’s poorest countries, a large majority of parents have no education. When there is little variation in parental education, it will be a poor predictor of individual socioeconomic status (i.e. it matters less what household one is born into when the large majority of parents are equally deprived), indicating a high level of relative mobility.

As countries develop and increase their levels of human capital, parental education levels will start to diverge. When these gaps become sufficiently large and are not adequately compensated for through public interventions, it will matter for an individual’s educational success whether s/he is born into a poor or better-off family (which in turn is correlated with parental education). Hence, in countries where the variation in social class is significant while the infrastructure needed to equalize opportunities may not yet be affordable, relative mobility is expected to be low.

When countries increase their national incomes further, they are likely to develop the fiscal space necessary to fund the type of public interventions that will give children born into disadvantaged backgrounds the opportunities to fulfill their potential (i.e. public interventions will partly compensate for inequalities in private investments). As the public interventions grow in size and effectiveness, relative mobility is expected to increase. This pattern is far from inevitable, though. To ensure that opportunities become more equal when countries develop, it is imperative that some of the extra fiscal space is indeed directed to public policies that expand opportunities for the worst off.

For more analysis on intergenerational mobility, see the new working paper.

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the UK government through the Data and Evidence for Tackling Extreme Poverty (DEEP) Research Programme.

Join the Conversation