Children in line for a daily meal in Ecuador. Photo: Jamie Martin / World Bank

Children in line for a daily meal in Ecuador. Photo: Jamie Martin / World Bank

2002. It was neither the best of times nor the worst of times. The world was facing growing division and sectarian violence as well as a global AIDS health crisis. Spray tans, low-rise skinny jeans, and small dogs as fashion accessories were all the rage in the United States. Europe was giving this new Euro thing a try. The world was watching the winter Olympics and the World Cup, plus the first Spiderman, second Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings, and fifth Star Wars movies, while Bollywood audiences thrilled for the first Raaz movie.

Against this roiling backdrop of world events, in May 2002 the World Bank released the Guidelines for Constructing Consumption Aggregates for Welfare Analysis. Authored by future Nobel laureate Angus Deaton and rising economist Salman Zaidi, the subtle green and white cover and unassuming citation as “Living Standard Measurement Study Working Paper No. 135” belied the profound and lasting impact the document would have on the practice of welfare measurement.

For 20 years, Deaton and Zaidi (2002) was the go-to reference for analysts both in national statistical offices and international organizations, and it presided over an unprecedented expansion of global poverty measurement. In 2002, only 63% of today’s low-income countries and 76% of today’s lower-middle-income countries had at least one official poverty measurement since 1960. By 2022, those figures have risen to 89% and 98% respectively.

Google Scholar, a search engine for scholarly literature, notes 1,306 official citations of the seminal report as of the writing of this blog, but that is likely a substantial underestimation of its impact considering that not all statistical abstracts and other official publications land in the database. Practitioners have expanded from a charming but oddball band of consultants and eggheads mainly affiliated with multilateral institutions to students, scholars, statisticians, and economists the world over.

But a lot has happened in 20 years. Despite new treatments for HIV and other improvements, the four horsemen of the apocalypse still keep busy. Tik Tok is now a thing. There are nine Spiderman and Star Wars, eight Harry Potter, six Lord of the Rings, and four Raaz movies, and there has been a similar explosion of literature in survey methods and poverty measurement. These events have led my fellow eggheads and I to wonder… but what about the Guidelines?

Enter Giulia Mancini and Giovanni Vecchi, accomplished academics from the University of Rome Tor Vergata with a solid record of research in welfare measurement. Three years ago, they heeded the request from my colleagues and I in the Data for Policy Global Solutions Group of the Poverty & Equity Practice to think about this question in light of the last 20 years of academic literature and common practice. Frodo Baggins, whose mission is to save the Middle-earth from destruction in Lord of the Rings, got off lightly compared to Mancini’s and Vecchi’s epic quest. The culmination of the scholarly adventure, On the Construction of a Consumption Aggregate for Inequality and Poverty Analysis, was released by the World Bank in March 2022.

The introduction describes the authors’ quandary in their journey to revisit the paper they affectionately call DZ:

At one end [of the spectrum] is replacement: an altogether revised set of guidelines, which would render DZ obsolete. We believe this is not attainable, other than by the original authors themselves. Even so, a complete rewriting would not be useful. In many aspects, the Guidelines are as sound as ever. At the other end of the spectrum, then, is repetition: a transliteration, a digest of DZ. This is clearly pointless. Our wish is to place this work somewhere in the middle: a reevaluation of sorts, acknowledging the developments in the literature since the late 1990s, as well as the changing needs of the Guidelines’ users.

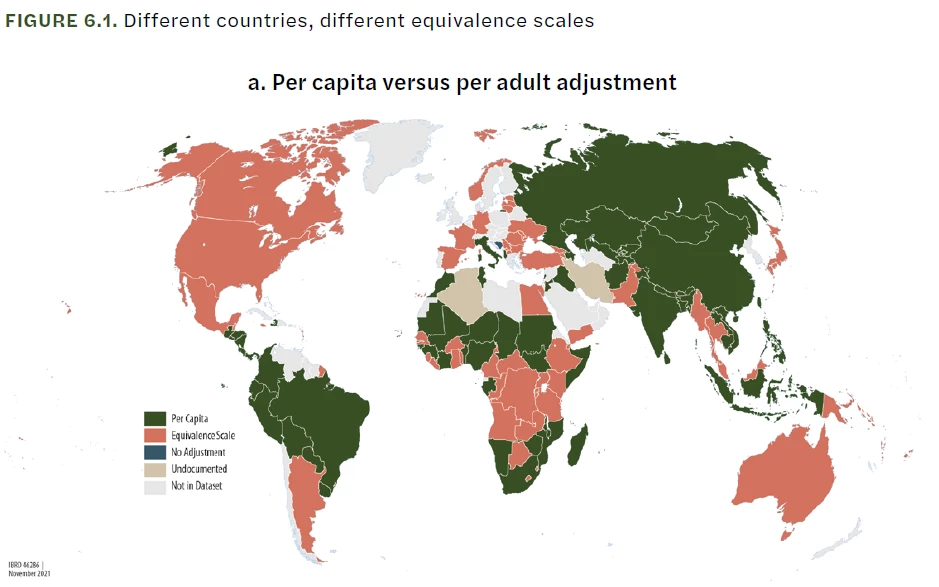

In my completely unbiased opinion, Mancini and Vecchi (2022) does just this, with great success: It answers the two key questions most asked by practitioners, “what is the standard approach globally?” and “what should I do in my specific context?” They reviewed 232 survey reports from 137 countries to document what is currently done but did not defer to the masses for best practices. Rather, the authors were thorough in reviewing the literature, making concrete recommendations where appropriate, and providing the pros and cons for areas where more work is needed.

In addition, there are new sections on topics that have increased in importance since 2002 — pricing food rations, replicability, documentation, and dealing with increasing non-response. The report closes with a set of cheat sheets comparing the scores of recommendations from Deaton and Zaidi and those of Mancini and Vecchi. These tables are striking for the number of times, after careful review, the authors declared, “The recommendation stands.” For the handful of exceptions including regarding the recall period for the food aggregate and health expenditures, the decisions are well-documented and thoroughly considered.

2022. In a hyperkinetic world enmeshed in difficult times, students, scholars, statisticians, economists, and assorted eggheads can take comfort in the fact that some things endure. Mancini and Vecchi join Deaton and Zaidi, and the Euro as enduring stores of value. 2002 can keep the low-rise skinny jeans.

Join the Conversation