The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has exerted a particularly heavy human and economic toll on low-income countries (LICs). Amid severe disruptions to activity, aggregate growth in the world’s 31 low-income countries this year is expected to fall to just 1 percent, the slowest pace in a generation. While activity is projected to firm in 2021, the outlook is subject to substantial downside risks. These include the possibility that mitigation and other control efforts to stem domestic outbreaks of the virus are unsuccessful or that measures to slow the spread—such as border closures—induce a food crisis. LICs will also face significant fiscal stress as a result of the pandemic and may require some form of debt restructuring, or even debt relief, to avoid sovereign defaults.

Measures to slow the spread, albeit necessary, have weighed heavily on activity

With the virus taking a heavy human toll, the necessary measures to slow its domestic spread have weighed heavily on LICs activity in the first half of this year. In addition, LICs face reduced external demand from a global economy ravaged by the crisis, falling commodity prices, a dramatic decrease in tourism activity, weakening foreign direct investment, higher borrowing costs, and an expected fall in remittances—a key source of foreign funding and support for household incomes in many LICs.

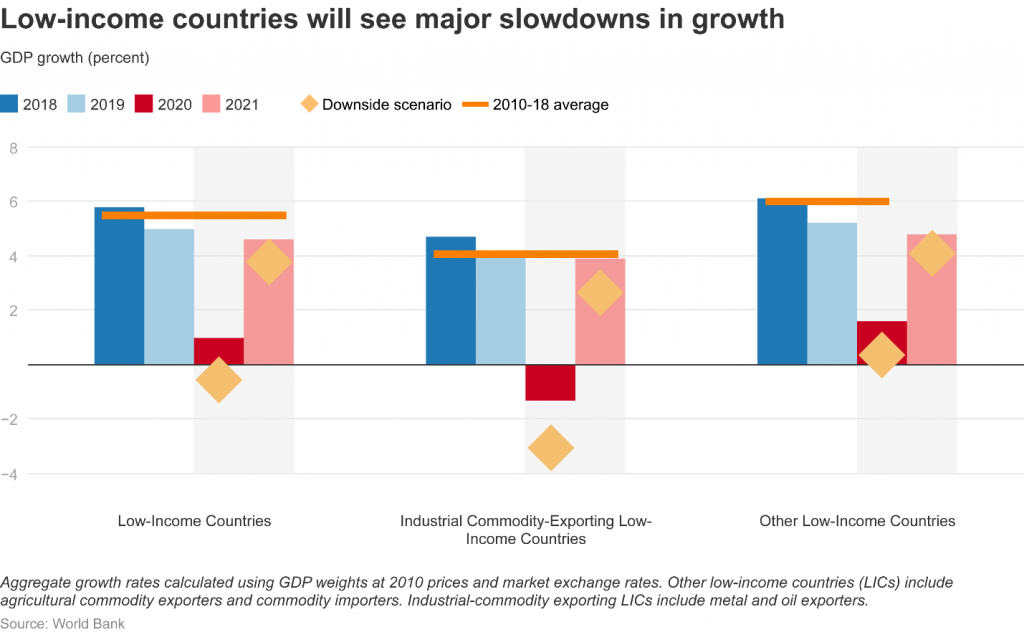

Growth is set to collapse to its slowest pace in more than 25 years

At 1 percent this year, growth among LICs will be 4.4 percentage points below our previous forecast in January 2020 and the slowest pace since 1994—reflecting the pandemic’s broad-based disruption to activity. Industrial commodity exporters will be the hardest hit economically, with growth expected to contract by 1.3 percent in 2020, as low commodity prices compound domestic disruptions. Although aggregate activity in LICs is expected to rebound in 2021 as headwinds related to the pandemic fade, significant uncertainty surrounds the pace and timing of the projected recovery. A longer-lasting and more severe pandemic would trigger an even steeper collapse in activity.

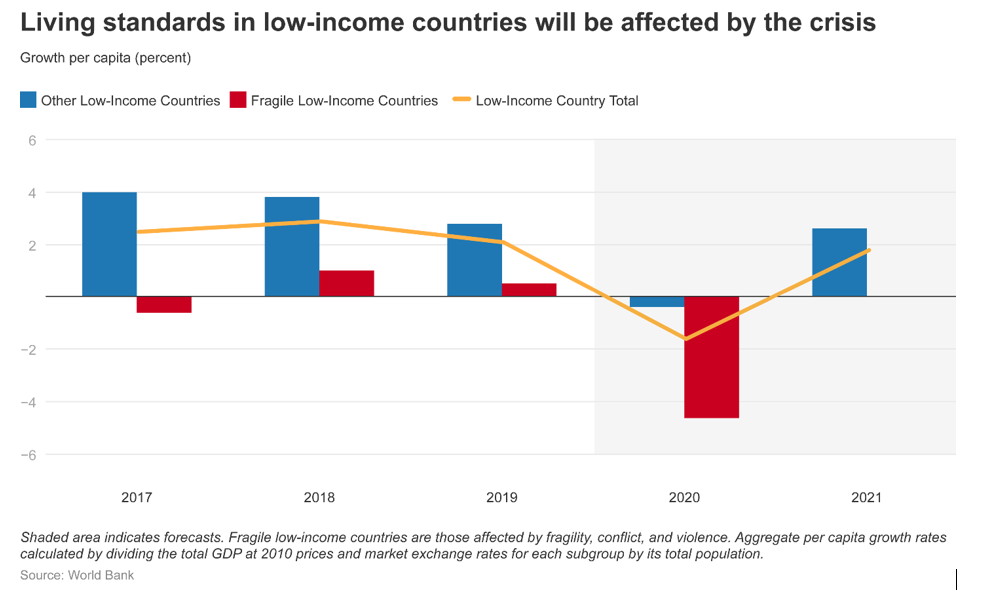

Prospects for per capita incomes and poverty are dire

Living standards in LICs will be markedly affected, with per capita GDP expected to contract by 1.6 percent in 2020. As a result of the pandemic, a large share of the population in low-income countries may slip back into extreme poverty, while those already in extreme poverty could descend further into destitution. Amid widespread informality, options to buffer temporary income losses are mostly limited. Among fragile LICs—where the incidence of extreme poverty is higher—the fall in incomes is projected to be steeper.

Risks are firmly to the downside

A major risk is that infection outbreaks among the LICs intensify and affect larger shares of the population. The risk of propagation is high as LICs’ ability to cope are limited, with often weak administrative capacity and insufficient health care systems. Even before this crisis, fiscal space in LICs was limited. Pandemic-related fiscal pressures to buttress health systems and provide support for the economy—while slowing activity dampens revenues—could put debt sustainability at risk in several low-income economies.

The pandemic may also lead to a food insecurity crisis among the LICs, as mitigation measures disrupt food supply chains, while also reducing access to critical inputs such as seeds and fertilizer, which could weigh on upcoming harvests. In addition, the pandemic has come on the heels of a locust infestation at the start of this year among several LICs, which is expected to intensify in the current growing season. Past infestations suggest the impact on food security could be significant.

Adverse effects could be long-lasting

Over the longer term, the pandemic is likely to have lasting adverse effects on LICs, as it may dampen potential growth prospects, reduce productivity, and diminish welfare. The impact of prolonged school closures, along with disruptions to school feeding and early-childhood development programs, is expected to set back human capital development, especially among the most vulnerable. Moreover, constrained fiscal space is likely to further weigh on needed development spending—particularly on health, education, and infrastructure—most possibly pushing these countries’ achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals over the next decade out of reach.

Join the Conversation