Sittipong Phokawattana / Shutterstock

Sittipong Phokawattana / Shutterstock

The economic scorecard of countries with parallel exchange rate markets has typically been extraordinary in all the wrong ways . High and chronic inflation, poor growth, and low control of corruption are common features among this group. Capital controls, often introduced or intensified in response to an adverse shock or a marked deterioration in economic conditions, trigger the birth of parallel markets. But whatever the context or root cause, a dearth of foreign currency available to the public is the proximate reason for the emergence, and persistence, of parallel or black markets and the result is often distortionary. What’s more troubling is that parallel markets are on the rise. Almost a fifth (28) of emerging and developing economies (EMDEs) now have active parallel currency markets – the highest number in over 20 years 1. Parallel markets intensified recently with the COVID-19 pandemic through its initial impact on commodity prices and more lasting supply chain disruptions for critical goods and services. The Russia-Ukraine war and the associated sanctions and financial market fragmentation may likely add more countries to that list, including in the Caucasus and Central Asia2.

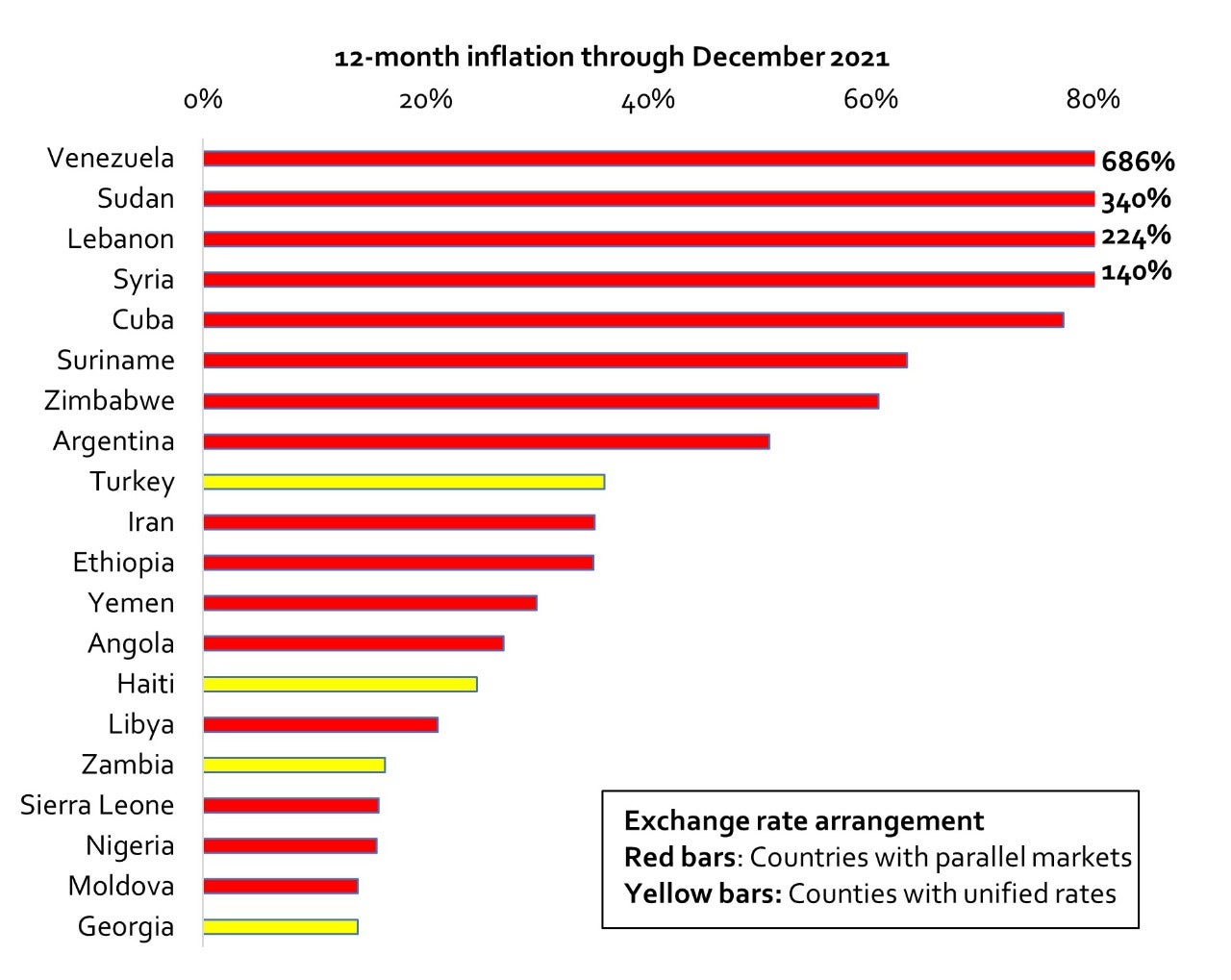

Economies with parallel exchange rates are notoriously inflationary . Of the 20 countries with the highest inflation rates for 2021, more than three-quarters have parallel markets (Figure 1). From January 2020 through December 2021, the probability of 12-month inflation rates 40 percent or higher for countries with parallel exchange rates is about 36 percent; for countries with unified exchange markets the odds were zero; Turkey marks the first exception if the sample is extended to January 20223.

Figure 1. The Top 20: Countries with the Highest Inflation Rates During 2021 (12-month percent change)

Sources: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics, Trading Economics, various country statistical agencies, and Graf von Luckner and Reinhart (2022).

Notes: The 12-month inflation rate for Syria and Haiti are through November and September 2021, respectively.

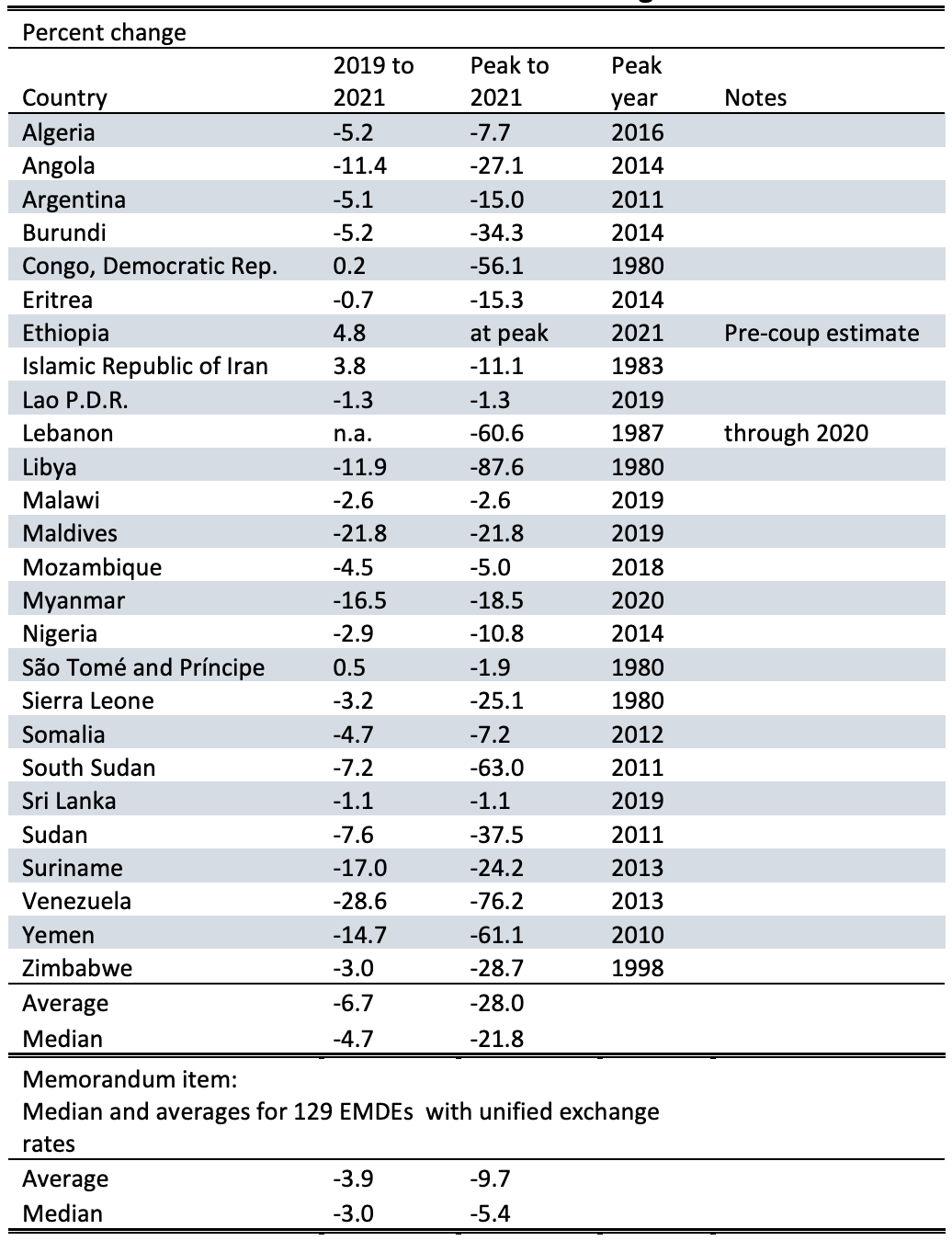

Historical growth performance (1970-2001) under parallel exchange rates regimes is also poor. Real per capita GDP growth in countries with parallel exchange rates was less than half that of countries with unified rates. Recent evidence points in the same direction. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, per capita incomes have declined for most EMDEs and for many the decline started well before the pandemic. However, the contraction from 2019 to 2021 is more severe for countries with parallel exchange rates than for other EMDEs, with a median decline of 4.7 percent versus 3 percent (Table 1). Comparing 2021 per capita GDP to its prior peak, the contrast is even sharper. The median decline for the parallel market group is about 22 percent versus about 5 percent for the countries with unified rates. The common pattern that emerges is one of multi-year secular contractions. Additionally, per capita GDP is known to correlate with a broad array of social and economic indicators. It is thus reasonable to conjecture that the comparatively poor performance of countries with parallel markets extends to other dimensions.

Table 1. Growth Declines in Countries with Parallel Exchange Rates

Sources: World Economic Outlook, IMF and authors’ calculations.

Note: Real GDP data is unavailable for Cuba and Syria.

Parallel premia (the differential between the official and parallel exchange rates) vary widely (Lebanon’s at about 1,400% currently sets the upper bound) and are often seen as a quantifiable measure of policy dysfunction. Yet, it is important to color this interpretation. Countries are more likely to introduce capital controls during bad times, inducing parallel markets, which in turn often deepen the issues leading to “doom loops”, so causation is seldom unidirectional.

These premia are also telltale signs of pressures on a sovereign’s external sector and often presage external debt distress. For example, over the last fifteen years, 2006-2021, five low-income countries have seen significant parallel currency markets arise, bringing the total to 115. Nine of these are currently either at high risk of, or in, debt distress. More broadly, all the sovereigns with parallel currency markets rated by the major agencies are in the highly-to-extremely speculative risk categories.

But the impacts of parallel markets extend beyond headline macroeconomic indicators. Whenever a coveted good (or currency, in this case) is available at a controlled price to a subset of the population, opportunities to profit exist; the connection between corruption and parallel currency markets is not new. The literature is replete with studies highlighting how parallel markets lend themselves to corrupt practices6. There are 209 countries and territories ranked in the 2020 Worldwide Governance Indicators. From the 28 which currently have parallel exchange rate markets, only 1 country is ranked above the 50th percentile in Control of Corruption, while the median percentile for this group is 13.94 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. WGI 2020: Control of corruption rankings for countries with parallel exchange rate markets

Source: Worldwide Governance Indicators 2020, The World Bank.

Notes: This index reflects perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as "capture" of the state by elites and private interests.

The combination of poor performance on inflation, growth, the control of corruption, and, possibly, many other economic and socio-political dimensions is a powerful deterrent to both domestic and foreign investment – and more generally, an impediment to equitable growth and development. Sustained capital flight has been a recurring feature of parallel markets, particularly during periods of higher premia. Still, fears that exchange rate unification will lead to an inflation spike are frequently cited as a deterrent to changing the status quo. Such fears are not without foundation but tend to be overstated, as this is a short-run effect7. Additionally, the economic distortions caused by parallel markets become harder and costlier to correct the longer they are present.

In response to this experience and the potentially distortive effects on country statistics from parallel markets, the World Bank is endeavoring to account for the emergence of multiple markets in currency conversions in the World Development Indicators (WDI) economic series. To this effect, the Bank recently conducted a pilot data collection program on parallel exchange rates. Based on this pilot, data collection processes for WDI economic series were revised to ensure ongoing identification of arising parallel market activity and regular collection of parallel exchange rate data to be used in surveillance and monitoring. And although information is sometimes incomplete and measurement is challenging, this initiative represents a step toward enhancing transparency and strengthening the quality of data.

Join the Conversation