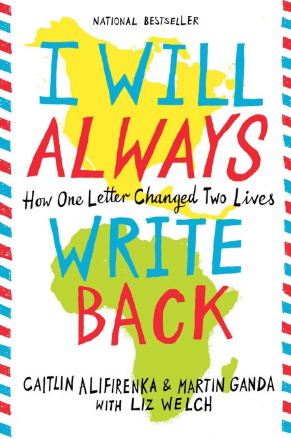

I Will Always Write Back is the true story of Martin Ganda and Caitlin Alifirenka, who became pen pals -- between Zimbabwe and the USA -- in middle (or lower secondary) school. Over time, they learn from each other, and ultimately Caitlin's family realizes the depth of need of Martin and his family -- living in a slum on the outskirts of the city Matate -- and provides support beyond the letters, all to an inspiring end (which I won't spoil).

I Will Always Write Back is the true story of Martin Ganda and Caitlin Alifirenka, who became pen pals -- between Zimbabwe and the USA -- in middle (or lower secondary) school. Over time, they learn from each other, and ultimately Caitlin's family realizes the depth of need of Martin and his family -- living in a slum on the outskirts of the city Matate -- and provides support beyond the letters, all to an inspiring end (which I won't spoil).

This book is on many middle school reading lists, with good reason. My thirteen-year-old son just read and enjoyed it. It provides an introduction to life in Zimbabwe and a range of challenges that might never occur to a child (or adult, for that matter) in a high-income country. I've never worked in Zimbabwe, but I have studied education in many countries, including several countries around Sub-Saharan Africa, and the characterizations of life broadly rang true.

How the story lines up with the evidence

Of course, this is just one story. But it lines up with recent research evidence on more formal child sponsorship programs. (Although the story in the book in a pen pal program, it evolves into a sponsorship arrangement.) Wydick, Glewwe, and Rutledge examine the impact of child sponsorship on outcomes in adulthood across 6 countries. They "find large and statistically significant impacts from child sponsorship on years of completed schooling, primary, secondary, and tertiary school completion, and on the probability and quality of adult employment." In another study, the same authors find that sponsorship "raised monthly income by approximately $15 over an untreated baseline of $75, principally from increasing future labor market participation." The figure below shows how that difference played out over time. Of course, not all sponsorship programs are the same; these results are from one program, Compassion International.

Source: Wydick, Glewwe, and Rutledge 2017

The narrative of I Will Always Write Back on parental aspirations for their children also lines up with evidence. In the book, Martin's mother tells him that "school is your only hope," and she encourages him to be number one, as in this anecdote: "At the end of first grade, there was a ceremony where the top three students were named. ... When my name was called for number one, I heard a joyous cry from behind me. I turned to see my mother jumping up and down, like a rabbit, ululating, which is how we celebrate.... On our way home, my mother said, 'Martin, if you want to do well in life, you must always be number one.'" The recently released World Development Report 2018 -- LEARNING to Realize Education's Promise -- confirms this: "Most parents want their children to go to school.... In a survey of Indian mothers with an average of less than three years of education, 94 percent hoped their children would complete at least grade 10. In Kenya, among parents with no education at all, more than half wanted a university education for their children."

The danger of a single story

In her insightful TED talk entitled "The Danger of a Single Story" (video, transcript), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi outlines the risks of believing there is just one story about any group, whether it's a single Nigerian story (a prince asking you to help transfer money) or a single Mexican story (a desperate refugee). There are always many stories, many Nigerians and Mexicans and others living all kinds of lives. I worry about the danger of Martin Ganda's story becoming the "single story." You see, Martin was a very special young man. Martin's school headmaster tells Caitlin's mother, "he is easily the brightest student we have ever seen in these parts -- smarter than many of his teachers." Despite poverty, Martin has a supportive family and is naturally bright. I'm very happy that he gained the opportunity to move forward in his life.

But what about the other children in Martin's class? What about all those children who aren't the "brightest student"? Martin Ganda is one person with one story. But other stories need to be told, stories of every child getting a chance to learn, even if they aren't the smartest child in the class. We know from evidence in Burkina Faso and Malawi that parents often put their educational investments into children who they see as the most academically promising. One of my concerns when reading I Will Always Write Back is that it doesn't challenge the story where the brightest children are deserving of a rich educational experience and other children are not. Education is a human right, not just a right for those who start out smartest.

To be clear, I don't think it is this book's job to tell all the stories. Enjoy this one. But I hope we can see out other stories to remind us that every child merits the opportunity to learn.

Join the Conversation