© Anna Koblanck / IFC. Sarah, a business owner, is using mobile banking services.

© Anna Koblanck / IFC. Sarah, a business owner, is using mobile banking services.

Last week’s announcement of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences has focused attention on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), a type of methodological approach borrowed from medicine and now widely used in development economics. So it seems an opportune time to report on our latest RCT, about the impact of digital financial services. This RCT has, once again, helped us show how digital transformation can improve livelihoods of rural households.

In rural Uganda, paying bills or transferring money is not only time-consuming but also costly due to high fees paid to intermediary agents, long distance traveled, and insecurity of carrying cash. In this setting, providing people living in rural areas with the possibility of making financial transactions on their phone can provide cost savings and increase the incomes of the rural residents. Using a RCT approach, we studied some of the remotest places of Northern Uganda to understand if and how poor rural households benefit from digital financial services. We find that they did.

Digital financial services have spread rapidly in developing countries, enabling people to make financial transactions on their mobile phones, such as transferring money, buying airtime, and paying bills. Mobile money is one such service that has helped households to receive more remittances, to withstand shocks, and to escape poverty in the long run.

Many of the previous studies on the impact of digital financial services around the world were implemented in areas that were less poor and less remote than the rural North of Uganda. We aimed at understanding better whether these positive impacts still hold in locations where remittances and mobile phone use are less prevalent than in previous studies.

What were we interested to find?

Apart from poverty rates which can be as high as 40 percent in rural northern Uganda, areas in our sample also have low access to financial services, with the average distance to a bank being 25 km or almost 16 miles. Only 28 percent of households own a mobile phone. This is much lower than the national average mobile phone ownership of 71 percent.

To measure the effect of mobile money in poor and remote areas, we collaborated with Airtel Uganda to implement a field experiment in Northern Uganda covering a geographic area of approximately 125,000 square kilometers. We randomly assigned 334 clusters of enumeration areas (defined by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics for census data collection) to a treatment or a control group and implemented two surveys in each of the areas, one at baseline (conducted in December 2015 and January 2016) and one after the completion of a successful rollout of mobile money agents in treatment areas (conducted in in January and February 2018).

In the treatment group, Airtel Money agents were rolled out in 2017, with about half of all our clusters receiving at least one agent. Mobile money agents offer a variety of services including deposit and withdrawal of cash, purchase of airtime, sending and receiving money, payment of bills such as school fees and utilities, and payment for goods and services. Agents often also help their customers undertake transactions and use their mobile money accounts.

What did we find?

Data on about 4,000 households from the 2018 follow-up survey show that the agent rollout increased the percentage of households using mobile money by about 4 percentage points (from 13 percent in the control group to 17 percent in the treatment group) in clusters far from a bank branch, defined as living farther than 25 kilometers from a bank.

In addition, the agent rollout reduced the cost of remittance transactions since it allowed households to walk to the agent instead of taking a motorcycle or mini-bus taxi. In line with previous literature, administrative data from Airtel on mobile money transactions also suggest that the agent rollout increased the probability of sending and receiving electronic money transfers.

Figure 1: Problems with Sending or Receiving Money Reported by Survey Respondent

The agent rollout increased the fraction of households who worked in self-employment off the farm by 3 percentage points in areas far from a bank branch. This is important as households are able to increase their total income by generating income from non-farm and farm employment.

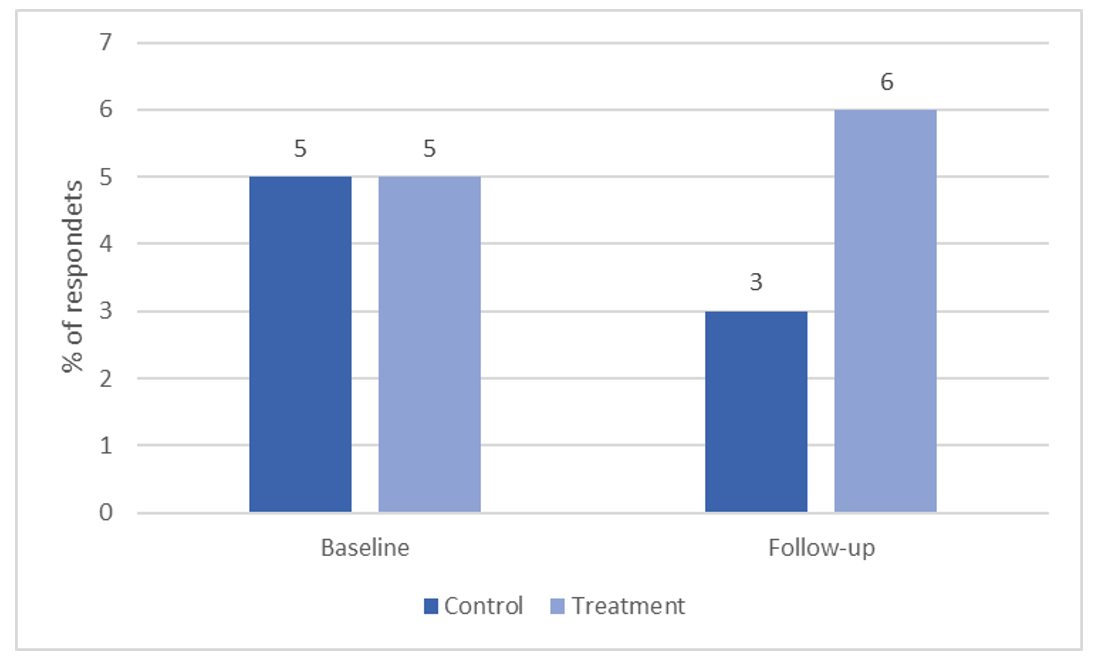

Figure 2: Works in Non-Farm Self-Employment

The agent rollout also changed the way in which households respond to negative shocks, such as a drought or flood. It increased the probability of working to cope with the shock and reduced the probability of compromising on the household’s diet. These findings are particularly important in rural Northern Uganda where households relying on farm employment are often faced with external shocks such as droughts which negatively impact the households’ income and as a result can reduce the number of meals eaten or the quality of diet.

In line with this result, the experiment also had a strong positive effect on food security. In areas far from a bank branch, it lowered the probability of having to reduce the number of meals in the 7 days preceeding the survey by 12 percentage points (from 37 percent in treatment to 49 percent in the control group).

We therefore conclude that mobile money stimulates self-employment and increases food security in rural Northern Uganda. Most importantly, these results provide strong evidence that mobile money services can improve livelihoods even in very poor and remote areas. This points to the importance of continuing our engagement on partnering with our clients, such as mobile network operators, payment service providers, or fintech companies, to increase the reach and breadth of digital financial services to poor communities who currently have limited or no access to these services.

The RCT study was a joint effort by the International Finance Corporation’s Digital Financial Services Advisory, the World Bank’s Research Department, and the Poverty and Equity Global Practice. It was funded by the Gates Foundation and implemented through the IFC-MasterCard Foundation Partnership for Financial Inclusion.

Join the Conversation