African widows often face considerable disadvantage relative to married women in their first union. How much so depends on the society they live in, with pronounced hardship in some contexts, yet benefits to widows in others. In the absence of effective policies, their situation is likely to depend heavily on the social-cultural norms applying to women following widowhood. In a recent paper, Annamaria Milazzo and I investigate this issue by comparing the well-being (as measured by BMI and rates of underweight) of young (15-49) Nigerian widows and non-widows across Christian and Muslim groups using the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of 2008 and 2013.

We focus on Nigeria because the ill-treatment of widows is a grave concern there as evidenced by the literature on the indignities and economic consequences of widowhood, the many NGOs focused on the rights of widows, public opinion surveys and DHS data pointing to considerable dispossession among, and violence against widows. We focus on religious groups because of the different processes that the sequel to marriage dissolution takes across the two religions: Islamic inheritance law stipulates a better treatment of widows than does customary family law which often applies to Christians. Islam as practiced in West Africa provides a semblance of a safety net to women who have suffered marriage dissolution, through high, and socially expected, remarriage rates facilitated by the continued practice of polygamy. These differences suggest that widowhood may not have the same consequences for the two groups.

Muslims account for roughly half the population of Nigeria but they tend to live in different areas to Christians, predominating in historically disadvantaged areas with higher poverty and worse access to basic social and infrastructure services. This is reflected in a pronounced and significant average gap in nutritional status that favors Christian over Muslim women (Fig 1 shows BMI, but the pattern is similar for underweight). This overall Muslim BMI disadvantage is found to be almost entirely explained by women’s worse individual and household level characteristics.

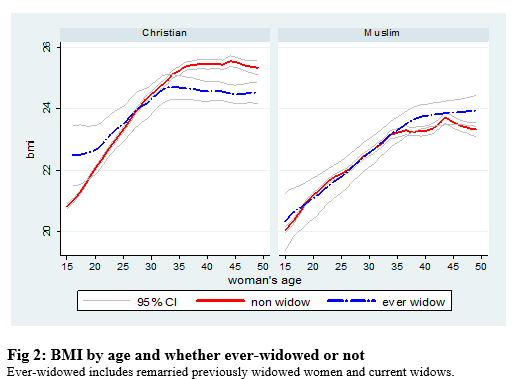

However, a noticeably different picture emerges when women are disaggregated into those who have never been widowed and those who have (Fig 2). Strikingly, the religious gap in BMI is largest for non-widows, and considerably smaller for widowed women, especially at older ages where more widows are found. In fact, the BMI gap is not statistically significant at ages over 40. Indeed, relative to married-once women in each religious group, current widows are found to be disadvantaged among Christian but not among Muslim women. And, remarkably, once women’s attributes are taken into account, the direction of the gap reverses among widows. The paper’s key finding is that among Christians, widowhood is associated with worse nutritional status while it is the opposite among Muslims.

The patterns found in the data provide support for the relevance of religion-specific norms regarding widowhood in explaining our findings independently of other factors that may drive differences across religious groups due to individuals living in different places or belonging to different ethnic groups. Christian widows also report a higher incidence of cruelty and violence at the hands of in-laws and consistently inferior inheritance outcomes, including significantly higher rates of dispossession than do Muslim widows. The greater acceptability and ease of remarriage through the practice of polygamy also favors widowed Muslims. The revealed nutritional status differentials among widows may or may not be influenced by such practices. At a minimum, they are undoubtedly a reflection of the same socio-cultural norms and processes that attend the shock of a husband’s loss.

A more or less equal share of Muslim and Christian women experience widowhood. But once it happens, cultural and religious norms combine with a women’s reproductive history and attributes, to determine a widow’s welfare and life outcomes. Muslim widows fare better despite their worse overall endowments.

Our paper provides new evidence that such practices have impacts on physical wellbeing. Recent research documents the presence of excessive deaths and undernutrition among widows in Africa. We argue that more favorable inheritance rules and social norms that more readily accept and encourage remarriage appear to considerably ease the shock of widowhood for Muslim relative to Christian women in Nigeria. The socio-cultural-religious norms and processes that follow widowhood for Muslim women clearly go some way to protect their health and well-being. The results point to the important role that policy could play in protecting often young women who experience the misfortune of widowhood.

Join the Conversation