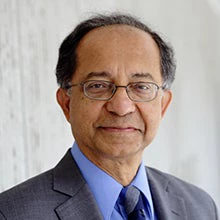

The same was true as I headed to Samoa. The flight was full of Samoans who could have walked out of a Paul Gauguin frieze, a few surfers and some missionaries. Jimmy Olazo and I from the World Bank did not fit into any of these categories and faced the inevitable interrogation on why we were going there. Samoa is indeed an unusual country to visit. It is impossibly small, with a population of less than 200,000. Its resources are meager, consisting of fish, some agricultural products and spectacular scenery. To an economist the viability of an economy like this is a conundrum. Where do you get the economies of scale from to produce your cars, hospitals, clothes? How much fish and tourism can you supply to the rest of the world to pay for these? Is it possible to help Samoans organize a steady flow of workers, skilled and unskilled, to other nations and rely on their remittances? How do you provide any insurance against the risks of natural disaster and calamity, a concern that, as I discovered over the next three days, dominated the lives of the Samoans? How do you conduct monetary policy in such an impossibly small nation?

These and other questions overwhelmed me during my brief, 3-day visit. I found answers to some, there were many queries that remained a puzzle, and I developed ideas on strategies that can be used to mitigate risk and help the Samoan economy. I had long meetings with the Prime Minister, Tuilaepa Aiono Sailele Malielegaoi, the Finance Minister, Faumuina Tiatia Faaolatane Liuga, the Governor of the central bank, Atalina Ainuu Enari (a woman), senior officials of the health ministry--impressively, 7 women and 1 uncomfortable man. Details of all these will go into reports and my Back to Office Report and need not detain us here in the cryptic pages of a blog.

Samoa rekindled in me what I have long admitted being--a closet anthropologist. This happened as I flew in reading Margaret Mead's Coming of Age in Western Samoa, which begins with all the evocation of a morning raga: “The life of the day begins at dawn, ...the shouts of the young men may be heard before dawn from the hillside. Uneasy in the night, populous with ghosts, they shout lustily to one another as they hasten with their work. … As the dawn begins to fall among the soft brown roofs and the slender palm trees stand out against a colourless, gleaming sea, lovers slip home from trysts beneath the palm trees or in the shadow of beached canoes, that the light may find each sleeper in his appointed place. Cocks crow negligently and a shrill voiced bird cries from the breadfruit trees.”

I am aware that the accuracy of Mead’s Samoan anthropology has been called into question but, nevertheless, these lyrical lines capture the spirit of Samoa. It may be a form of geographic infidelity on my part that the last country I have visited seems the best, a place I could settle down in, like Robert Louis Stevenson did in a sprawling estate just outside Samoa's capital 'city', Apia. Having just left Samoa, that is exactly the way I feel—it is the most beautiful place on earth, with rolling hills, tropical flowers, gentle people ("the people are mellow," in the words of the young owner of the one Indian restaurant in the nation) and no sense of urgency. On the last day, before catching my flight out, I, along with Jimmy, Maeva and Antonia, attempted to climb the peak where the great writer lies buried. From the slopes of the hill one gets a majestic, panoramic view of this impossible kingdom and a sense of what lured Stevenson.

There are contemporary examples of outsiders settling down here. One morning we go to meet Vanya Taule’Alo a short drive from Apia. Vanya is a remarkable woman who came from New Zealand in 1976 married a local—I assume that’s how she got the Taule’Alo—and made her home in this village. She now spends her time painting and running an art gallery, displaying the handicrafts and arts of local Samoans. Her own art is remarkably original and imaginative and her home, which she opened up to us with a little persuasion, is itself a work of art.

All this cannot blind us to the fact that Samoa has its share of troubles. It is a poor nation, living on the edge of disaster (Cyclone Evan alone, in December 2012, destroyed 16% of the nation’s assets), with few luxuries of modern life. Yet, it has magical qualities. There is poverty (with 3% of the population below the $1.25 a day poverty line)but there is no squalor. This is so baffling that to someone familiar with poverty in sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia, it is easy to be deluded into thinking there is no poverty here. Indeed one is confronted with troubling questions about the use of a common poverty metric across nations as varied as Samoa, Senegal and South Africa. There is a jail, and there are, I am told, inmates, but crime in this nation is negligible. I learned later that the police in Samoa, unlike ordinary citizens in the United States, are not allowed to carry guns.

There is hierarchy and elitism but I could not help admiring the fact that soon after I left the bustling fish market on Sunday morning having watched the fishermen sell their catch to ordinary folks including women adorning their hair with tropical flowers like in the Gauguin paintings, soon after sun rise, the Prime Minister was there buying fish for himself and his family. (As a man who was at the market later told me, "You may not have recognized him because he was wearing a hat.")

At first sight, the Islanders seem overweight. But that is simply a reminder that many of our perceptions are socially conditioned. The natural grace of the people soon obliterates any awareness of this. As the local newspaper, the Samoa Observer, noted pithily about the beautiful Miss World contestant from the island, Penina Maree Paeu, she "defies the beauty pagent stereotypes."

The Indian restaurant I mentioned above is called Tifaimoana. We were seeing it during our many rounds up and down Apia. So on the last night Jimmy and I decided to walk down there from our hotel, Tanoa Tusitala. It was rather late when we set out. The roads were deserted, barring a few stragglers and stray dogs. I was curious to find out who this romantic soul was who had travelled so far to set up a restaurant. Its manager turned out to be a young man from Kalyan, Mumbai. Three years ago his brother-in-law who has some business in Fiji came here and did a back-of-the-envelope calculation about the financial viability of an Indian restaurant in Samoa. They brought in two cooks from Dehradun, one to run the tandoor and the other everything else. They hired local helping hands and Tifaimoana was founded, and judging by the fingers that were being licked and the slurping sound of the seven or eight late night diners, it was serving what till its founding was a latent Nurksian demand.

I am aware that it is easy for an outsider to be overwhelmed by Samoa's irresistible charm and overlook the many challenges this tiny nation faces. To do so will do injustice to its people. Samoa's big challenge is the environment. This is one place where global warming and the rising sea level are not academic matters. Every citizen of this nation is aware of this. The increased incidence of natural disasters--the tsunami in 2009 and cyclone Evan in late 2012 are the most recent reminders of this. I travelled extensively and saw the ravages left by these. The place where the tsunami struck is like a picture postcard of Pacific island beauty. The catch is that between the shore and the steep mountains is just a sliver of land. When the tsunami came the people were trapped; scrambling up the hills hurriedly, many failed to beat the waves and the casualty was high.

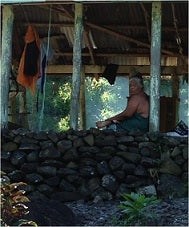

There is a lot of ongoing activity, building escape paths to scramble up the hill slopes, making roads to then make ones way to other more urban centers, and putting in systems of sirens and announcements to inform residents of approaching storms and tsunamis. There is also need to move some important buildings like schools to higher areas, since global warming will continue for some more time even if we are able to eventually arrest it. Samoa is not a rich nation and there is desperate need for ongoing support to carry out these tasks as soon as possible. The World Bank is present all over the two main islands of this nation, Savai’I and Upolu, building roads and supporting other infrastructure but the challenges are many and there is need for more global support and engagement. As my three packed but wondrous days quickly came to an end and I prepared to leave Samoa, I asked an inhabitant of Apia, "Why is there so little crime and burglary in Samoa?" His answer came pat: "That is because our homes are completely open, with no walls and no doors. That's why no one dares to go in and steal." I have to admit that as I walked up the tarmac to the plane waiting to fly us over a vast expanse of the Pacific to Auckland I tried to dissect the logic of that retort and had to contend myself with the thought that this was a logic that worked only in Samoa, a country after my heart.

As my three packed but wondrous days quickly came to an end and I prepared to leave Samoa, I asked an inhabitant of Apia, "Why is there so little crime and burglary in Samoa?" His answer came pat: "That is because our homes are completely open, with no walls and no doors. That's why no one dares to go in and steal." I have to admit that as I walked up the tarmac to the plane waiting to fly us over a vast expanse of the Pacific to Auckland I tried to dissect the logic of that retort and had to contend myself with the thought that this was a logic that worked only in Samoa, a country after my heart.

Join the Conversation