Not so long ago, those countries designated as “low-income countries” (LICs) in the World Bank’s World Development Indicators accounted for the bulk of the world’s poor, such as by the $1.25 a day standard. Today many very poor people live instead in what are called “middle-income countries” (MICs). The change seems dramatic. Almost all (94%) of those below $1.25 a day in 1990 lived in LICs. By 2008 the proportion was down to 26%, with the rest in MICs. Andy Sumner attracted much attention to this aspect of how the global profile of poverty has changed in his paper “Where do the Poor Live?.” Amanda Glassman, Denizhan Duran and Sumner dub this emergence of large poverty counts in MICs as the “new bottom billion.”

There has been much discussion about the implications of this change for overseas development assistance (ODA) and development policy more broadly. In particular, there have been calls for concentrating ODA on the LICs, assuming that the MICs can now look after their own poor.

But we need to look more closely at this “LIC-MIC” distinction, to understand why we have seen this change in the global poverty profile, and what relevance it might have for development policy.

An influential but aging classification of uncertain origin

The World Bank assigns “LIC” and “MIC” status based on countries’ gross national income (GNI) per capita, using the so-called “Atlas method.” (This is based on a moving average of official exchange rates adjusted for inflation relative to the G5 countries. It is unclear why the Bank does not use its own PPP exchange rates for this purpose.) As best I can determine, the graduation threshold for going from LIC to MIC, as given here, was officially set in 1988 at the value of the Bank’s “Civil Works Preference” (CWP), which had been set at a GNI of $200 per capita in 1971. The threshold has only been updated over time for global inflation.

So this widely-used income threshold for becoming a “MIC” has been essentially fixed in real terms for over 40 years! Knowing this, it can hardly be surprising that the share of the poor (and, indeed, of the whole population) in LICs has declined over time. Naturally, the fact that the two most populous countries, China and India, recently crossed the threshold magnifies the effect dramatically.

And yet the relevance of this old MIC threshold to the development aid debate is far from clear. CWP status means that eligible domestic contractors from that country can be given preference in evaluating civil works bids for World Bank projects under international competitive bidding. It is unclear why the MIC threshold was tied to the CWP. It just seems to have been a convenient number on hand at the time. It is unclear why “arcane concerns with civil works preference” (as Charles Kenny has put it) are salient to development assistance choices.

Putting aside these issues, the question remains as to why we should treat equally poor people differently, depending on differences in the assigned status of the countries they live in. The “new bottom billion” are not really so new. People living below $1.25 a day in “middle-income” India and China are not some new set of families that have recently emerged. Roughly speaking, they are just as poor as before their countries graduated to MIC status. Why should we treat them any differently?

In response, one might argue that past economic growth points to lower expected future poverty, and that external development assistance would thus be better placed where there has been little or no such growth. (We can probably put aside theoretically possible but practically doubtful concerns about perverse incentive effects.) But then we still don’t have a rationale for using this “LIC-MIC” distinction. Would not this logic apply with equal force within these categories? We can measure growth at country level.

A deeper argument might be found in the fact that the nation state has a clear role in efforts to fight poverty, and states differ in their capacities for doing this well. The task of fighting poverty in MICs might then be seen as largely a matter of domestic policy—that MICs should typically be left to look after their own poor, with ODA focusing more on LICs.

But why is the fact of crossing this arbitrary old threshold of relevance to the capacity of countries for looking after their own poor? More careful treatments of the topic acknowledge MIC heterogeneity, though the nature of the differences relevant to aid allocations is rarely articulated. In a briefing note for the Center for Global Development, Andy Sumner points to India as an example of a MIC that has (he claims) “little need for ODA” despite having many very poor people. But it is not clear why he puts India in this category. (In fairness to Sumner, his recent paper, “Poor Countries or Poor People?” with Ravi Kanbur, provides a nuanced discussion of the reasons for caution in arguing that MICs can be safely left to tend to their own poor. But this does not tell us whether India, or some other MIC, does or does not need external assistance for fighting poverty.)

Some evidence on domestic capacity for redistribution

To inform discussions of aid policy, a better approach is to look instead at more direct measures of domestic capacity for fighting poverty. There are many aspects of that capacity one might focus on. (The World Bank’s allocations of its concessional lending use numerous indicators of domestic capacity and the quality of policies and institutions.) However, since much of the recent debate has concerned domestic capacity for directly intervening to help poor people, it is of interest to look more closely at this aspect. Is average income an adequate proxy for domestic capacity for fighting poverty through income redistribution?

In thinking about how one might address that question, we can reasonably assume that aid donors will not be indifferent to how incomes are distributed above the $1.25 poverty line when assessing a developing country’s capacity for redistribution to its own poor. It is clearly not acceptable to say that a country has a high capacity if (given its income distribution) redistribution would require putting almost all the tax burden on people living just above $1.25 a day. Some countries have greater affluence—with more people living well above the poverty line—than others, and this must be brought into the picture.

To help identify a defensible measure of domestic capacity for redistribution, it can be assumed that citizens of a rich country would find it intrinsically (ethically or politically) unacceptable to expect a developing country to address its poverty problem by taxing people who would be considered poor in the rich country. This leads us to focus on the capacity for redistribution from the “rich” to the “poor” within developing countries, with middle-incomes untouched.

Several arguments support this characterization of the capacity for redistribution. Popular judgments about “inequality” appear to give greater weight to redistributions from the rich to the poor than redistributions amongst the middle class or from the middle class to the poor. There are also instrumental arguments that point to the expected role of the middle class as agents of progress and also the likely incentive effects on those near the poverty line. One can also question the political feasibility within a given developing country of asking middle-income groups to shoulder the burden of poverty relief. Redistribution from the “rich” to the “poor,” without involving middle-incomes, can also emerge as a public choice equilibrium. This would require the usual conditions for the median voter theorem—namely that the issue to be voted on is one dimensional and the utility function is single-peaked in that dimension—plus the assumption that the decisive voters care sufficiently about poverty and are concentrated around the median, which is (invariably) below the mean.

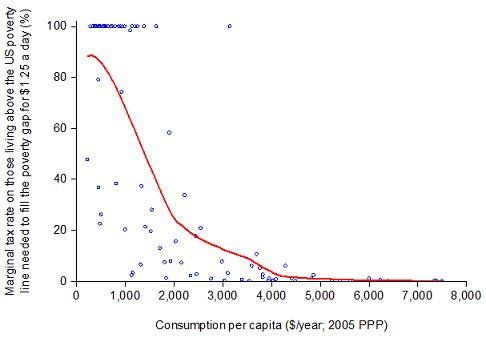

Following this idea, the “capacity for redistribution” of any developing country can be measured by the marginal tax rate (MTR) on those who are not poor by rich-country standards that is needed to cover the domestic poverty gap—the aggregate deficit of poor people relative to the poverty line. I have proposed such a measure, in “Do Poorer Countries Have Less Capacity for Redistribution?.” The “non-poor” by Western standards are identified as those living above the US poverty line of $13 a day in 2005. And the poverty gap is judged by the $1.25 a day standard. So an MTR of (say) 25% means that a tax of $1 for each $4 of extra income above $13 a day would generate sufficient revenue to cover the poverty gap relative to $1.25 a day. Figure 1 shows how my calculated value of this marginal tax rate varies across countries, according to their mean consumption. (Whether one uses mean consumption or mean income is unlikely to make much difference for this purpose.)

This suggests that there is a positive correlation between domestic capacity for redistribution (as indicated by a low required MTR) and average income. I find that for most (but not all) countries with annual consumption per capita under $2,000 the required tax burdens are prohibitive—often calling for marginal tax rates of 100 percent or more. By contrast, the required tax rates are very low (1% on average) among all countries with consumption per capita over $4,000, as well as some poorer countries.

Figure 1: Marginal tax rates on the non-poor by US standards needed to cover the poverty gap by poor country standards across developing countries

Note: MTR’s are truncated at 100%. Source: www.degruyter.com

However, notice how much the marginal tax rates vary across countries at a given mean consumption (or income). For countries in the region $1,000-2,000 per year, the tax rates vary from close to zero to 100%. Average consumption or income is clearly not a good proxy for a country’s capacity for fighting poverty through internal redistribution.

It is instructive to see where India is found. My calculations indicate that the tax on the non-poor (by Western standards) needed to cover India’s poverty gap would be truly prohibitive. Not even a tax rate of 100% would be sufficient! Indeed, appropriating all of the incomes of those living in India above the US poverty line would cover only a modest fraction of the country’s aggregate poverty gap.

This simple arithmetic leads me to question whether India can yet be considered to have ample capacity for eliminating poverty by domestic redistribution. By contrast, China could generate revenue sufficient to cover the poverty gap with a more modest (though hardly small) marginal tax rate of 37% on incomes of the non-poor by US standards. (Although in some provinces of China, the required tax rates could well be much higher.)

In conclusion

The global community would not need to worry so much about the many very poor people living in “middle-income countries” if it could be reasonably confident that any country attaining such a designation is capable of tackling its own poverty without external help. But that is plainly not the case. Merely knowing whether a country’s average income puts it above or below the arbitrary historical threshold used to delineate “low-income” from “middle-income” countries tells us rather little about key aspects of the country’s capacity for fighting poverty, including through domestic redistribution.

Future success against poverty will depend heavily on the policies adopted by governments in developing countries, at all income levels. While there is scope for better redistributive policies even if they can’t reasonably be expected to solve the poverty problem, supporting economic growth will continue to play an important role in fighting poverty. Domestic policy changes will often be needed to assure higher growth. And in many countries, those changes will have to include effective efforts to redress the pervasive inequalities that constrain the economic opportunities of poor people.

While such domestic policies will continue to play a crucial role in fighting poverty, external development assistance can still help, including in the so-called “middle-income countries.” This includes assistance for developing the analytic and administrative capacity for designing and implementing better domestic policies.

And, by the way, is it not time for these arcane income thresholds for “graduating” from “low-income” status to be laid to rest?

Join the Conversation