In May 2013, officials of the Federal Reserve System first began to talk of the possibility of the U.S. central bank tapering its securities purchases (of it gradually reducing them from the prevailing $85 billion monthly rate to something lower, presumably as a prelude to phasing them out entirely). A milestone to which many observers point is May 22, 2013 when Chairman Bernanke raised the possibility of tapering in his testimony to the Congress. This “tapering talk” had a sharp negative impact on economic and financial conditions in emerging markets.

Three aspects of that impact are noteworthy. First, not only was the impact sharp but, in the view of many commentators, it was surprisingly large. The most alarmed (some would say alarmist) commentators raised the possibility that some emerging countries might be heading towards a full blown crisis like those in Mexico in 1994 and Asia in 1998. Second, the impact was not felt uniformly; different countries were affected rather differently. And, third, there were complaints from policy makers in the developing world about the Fed’s turn to tapering that were seemingly hard to square with earlier criticisms of quantitative easing by the U.S. central bank as a form of “currency war.”

In a new paper, we attempt to shed light on these issues. We use data for a cross section of emerging markets to analyze who was hit by the Fed’s tapering talk and why. We focus on the change in exchange rates, foreign reserves and equity prices between April 2013, just prior to talk of tapering, and August 2013, by which time the response was largely complete. (In September, new data on the condition of the U.S. economy led Federal Reserve officials to make statements that moderated prior expectations of tapering).

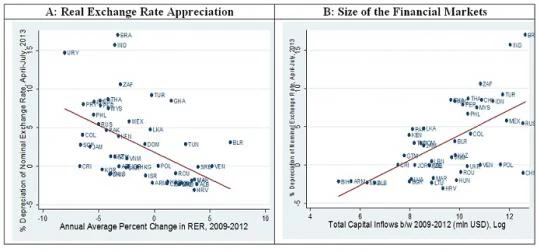

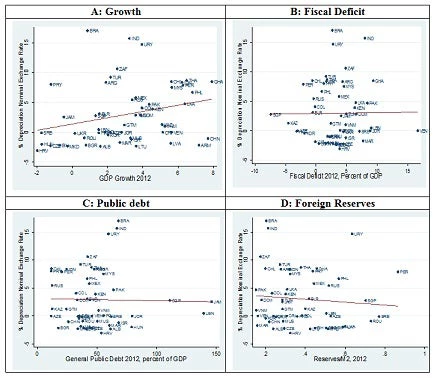

We relate the reaction of these variables to several classes of potential determinants: (a) observable macroeconomic fundamentals like the budget deficit, public debt, foreign reserves and GDP growth rate in the prior period; (b) the size and openness of a country’s financial markets; and (c) the extent to which capital-flow-sensitive indicators like the real exchange rate and current account balance had been allowed to move in the prior period when quantitative easing was underway, there had been no expectations of tapering, and policy makers in emerging markets had complained of currency wars.

On the basis of this analysis, our answers to the questions posed above are as follows.

First, there is little evidence that countries with stronger macroeconomic fundamentals (smaller budget deficits, lower debts, more reserves and stronger growth rates in the immediately prior period) were rewarded with smaller falls in exchange rates, foreign reserves and stock prices starting in May.

What mattered more was the size of their financial markets.[1] Investors seeking to rebalance their portfolios concentrated on emerging markets with relatively large and liquid financial systems; these were the markets where they could most easily sell without incurring losses and where there was the most scope for portfolio rebalancing. The obvious contrast is with so-called frontier markets with smaller and less liquid financial systems. This is a reminder that success at growing the financial sector can be a mixed blessing. Among other things, it can accentuate the impact on an economy of financial shocks emanating from outside.

In addition, we find that the largest impact of tapering was felt by countries that allowed exchange rates to run up most dramatically in the earlier period of expectations of continued ease on the part of the Federal Reserve, when large amounts of capital were flowing into emerging markets. Similarly, we find the largest impact in countries that allowed the current account deficit to widen most dramatically in the earlier period when it was easily financed. Countries that used policy and in some cases, perhaps, enjoyed good luck that allowed them to limit the rise in the real exchange rate and the growth of the current account deficit in the boom period suffered the smallest reversals. This provides some intuition for how it was that the same countries could complain about quantitative easing while it was underway — QE had large, disconcerting impacts on local markets — and then also complain about tapering talk. Their asset prices had been allowed to increase sharply and their current accounts had been allowed to widen relatively dramatically in the earlier period, and as a consequence, talk of tapering now had a relatively large negative impact on local markets.

We interpret these real exchange rate and current account measures as picking up the impact, positive, negative or neutral, of macroprudential policy broadly defined. Recall that we control for the stance of fiscal policy (since fiscal tightening can also limit the appreciation of asset prices in a period when capital is flowing in). In addition, we control for the intensity of capital controls in the prior period; these, similarly, do not appear to have exerted a consistently significant impact on the effects of tapering. Nor does their inclusion alter the estimated effect of the change in the real exchange rate. Evidently, neither capital controls, nor fiscal tightening, nor even a combination of the two, sufficed to damp down the effects of financial inflows. Instead, a broader array of macroprudential policies — limits on the rate of growth of bank lending, loan-to-value regulation for the mortgage market, and similar measures — which moderate the upward pressure on the exchange rate and the widening of the current account deficit may have made a difference, and may therefore be called for in the future.

Figure 1: Effect on Exchange Rate during April-July, 2013, Factors that Mattered

Figure 2: Effect on Exchange Rate during April-July, 2013, Factors that did not Matter

Join the Conversation