Former Soviet Union leader Joseph Stalin and famous Irish writer Oscar Wilde had very little in common. Yet they agreed on one thing: the importance of ideas in human life. The former once said: “Ideas are more powerful than guns. We would not let our enemies have guns, why should we let them have ideas?” The latter boldly wrote that “An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.” My colleagues who serve as regional chief economists at the Bank -- Shanta Devarajan, Kalpana Kochhar, Indermit Gill -- also agree with me that ideas drive various societal transformations. Nevertheless, they disagree with me on several points, as highlighted in their joint post on Africa Can. We all want to generate and channel the best knowledge on development to policymakers around the world who have been struggling for centuries—if not millennia—to lift their people out of poverty.

Reducing poverty and climbing the ladder to prosperity aren’t easy: From 1950-2008, only 28 economies in the world have reduced their gaps with US by 10 percent or more. Among those 28 economies, only 12 are non-European and non-oil exporters. Such a small number is sobering: It means that most countries have been trapped in middle-income or low-income status. As development economists, we must find a way to help them improve their performance so that our dream of “a world free of poverty” can be realized and they can close the gap with the high-income countries.

At the round table discussion during the recent World Bank-IMF Spring Meetings in Washington on April 18, I made the following main points: the first wave of development economics, which emerged as a new sub-discipline of the modern economics after World War II, was heavily influenced by structuralism. Emphasizing importance of structural change, it attributed the lack thereof to market failures and proposed government interventions to correct it, most notably via import substitution strategies, many of which failed. By the 1970s, a second wave of thinking led to a gradual shift to free market policies, which culminated in the Washington Consensus. It expected spontaneous structural change to occur as long as the markets remained free. Its policy framework consisted mainly of getting prices right through liberalization and privatization, ensuring macroeconomic stability, and improving governance. Its results were at best controversial and some have even characterized the 1980s and 1990s as the developing countries’ “lost decades”.

Because developing countries were not able to close the gap with high-income countries and because of persistent poverty, the international donor community shifted their efforts to humanitarian projects such as investing directly education and health for poor people. But service delivery remained disappointing in most countries. This led to a new focus on improving project performance, which researchers at the MIT’s ‘Poverty Action Lab’ have pioneered with randomized controlled experiments.

Commenting on the evolution of development thinking from early structuralism/Washington Consensus to project- or sector-based approaches, Michael Woolcock has written about a shift from "Big Development" to "Small Development". While it is clearly important to understand the determinants of project performance, it is questionable whether that is really the route to economic prosperity. After all, the only 12 economies that were able to close the gap with the US by 10 percent or more did not start their development journey with micro-projects but with big ideas.

In my roundtable presentation I suggested that development economists go back to Adam Smith—not to “the Wealth of Nations”, but to the Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Modern economic development in nature is a process of continuous structural changes in technology, industry, socioeconomic and political institutions. It did not appear until the 18th century—before that time every country in the world was poor and agrarian. But since then it has profoundly changed the world, especially those successful high-income industrialized countries.

Past development thinking failed to deliver results because they got either the nature or causes of modern economic growth wrong. Early structuralists were right to try to close the structural gaps between low-income and high-income countries. But they identified the wrong causes of the problem. They attributed the low-income countries’ inability to establish high-income countries’ advanced industries to market rigidities. Based on this assumption, they advocated inward-looking policies to build industries that in fact were not viable in open, competitive environments. While subsidies and protection allowed some countries to achieve high investment-led growth for a period of time, that strategy came with costly distortions and was not sustainable in the medium- to long-term. Certainly the approach could not help them converge to high-income country levels.

The ‘Washington Consensus’ shifted the policy pendulum towards market fundamentalism. By focusing obsessively on government failures and ignoring the structural issues they assumed that free markets will automatically create spontaneous forces to correct structural differences among countries. Yet market failures from externality and coordination are inherent in the process of structural change. Without the government’s facilitation, the spontaneous process that ignites the change is either too slow or never even happens in a country. Unfortunately, the ‘Washington Consensus’ neglected this. The Washington Consensus also neglected many existing distortions in a developing country are second-best arrangements to protect nonviable firms in the structuralism’s priority sectors in the country. Without addressing the firms’ viability, the attempt to eliminate those distortions could cause their collapse, large unemployment, and social and political instability. For fear of such dire consequences, many governments reintroduced disguised protections and subsidies which were even less efficient than the old subsidies and protections.

As the world’s leading development institution, the World Bank should spur the global development community to refocus its research and operations on the nature and causes of modern economic growth. It is very important that the Bank has the right knowledge agenda, given its convening power and influence in shaping development thinking and in influencing policies in developing countries and the world. It is imperative for the institution’s chief economists to play the intellectual leadership role in this knowledge bank.

Modern economic growth is a process of continuous structural change. In searching for the causes of structural change, I would like to highlight a few ideas:

First, it is vital to distinguish between “fundamental” causes and “proximate” causes. For example, innovation is a fundamental cause of structural change and education is a proximate cause. We should not treat a proximate cause as the ultimate cause. A case in point is what happened in North Africa, where education improved a lot, but structural change did not occur. This example reveals education to be a proximate rather than an ultimate cause.

Second, in understanding fundamental versus proximate causes, it is important to bear in mind the mechanisms and requirements for change differ in countries depending on their level of development. For example, while innovation in high-income countries amounts to invention as their technology and industry are on the global frontier, in developing countries it can be imitation. Because the mechanism of innovation is different for countries at different levels of development, the educational requirements also vary.

Third, pragmatism is paramount. Regardless of whether they try to address fundamental causes or proximate causes, many past and existing policy prescriptions for poor countries overlook that they will not be implemented in the context of a ‘first best’ world. In fact, all World Bank country clients are in the ‘second best’, ‘third best’, or even ‘nth best’ world. While we should understand what an ideal, first-best world looks like, our recommendations to be helpful should be pragmatic. One of the first lessons I learned at the University of Chicago was that removing distortions in a second-best situation does not necessarily result in a Pareto improvement and convert a country into a first-best environment.

Take the principle of pragmatism as it applies to Ethiopia, a low-income country with large population (80 million) where I recently visited. To structurally transform, the country needs technological improvements in agriculture and to develop low-skill and labor-intensive manufacturing sectors. Given its low level of domestic savings and weak or non-existent linkage to global production networks and distribution chains, it would be desirable to bring in foreign direct investment (FDI). However, the investment climate and business environment there are weak. In such situations, the Bank policy could follow two approaches: Look at Ethiopia through the lenses of a first-best world and recommend immediate removal of various distortions to improve the business and investment environment. The assumption would be that FDI will arrive spontaneously if that policy advice is followed. I am skeptical that would be the case. First, it may take decades for the improvement of business environment to reach the ideal level. Second, even after such improvements, FDI may not come spontaneously. To illustrate, Tunisia’s Doing Business Index ranked number 46 and Botswana ranked number 51 in 2012, among the highest among developing countries in the world, but FDI did not come to help bring in structural change in those two countries.

For Ethiopia I would suggest a second, more pragmatic approach. It consists of advising the authorities of policies that are more targeted and easily implemented. Let’s be humble and realistic and start with something small, like the high level of tariffs that impede FDI there. For instance if a company wants to import cars or equipment, it has to pay a high tariff, which impedes FDI. The conventional recommendation would be to remove all these tariffs. However, we must understand that currently Ethiopia does not have a car industry or equipment production industries, and thus the high tariffs are not meant for the protection of nonexistent domestic industries, but for generating revenues. Under those circumstances, advising the government to remove all these tariffs would lower public revenues and they will be unable to solve their foreign exchange shortage. A better solution is to recommend the development of industries, such as shoe, leather, and garment, sub-sectors where the country holds comparative advantages, can create jobs, generate revenue, and quickly become competitive in the world market. To start the process the Ethiopia government could remove tariffs in these targeted industries to attract FDI. For the government, the ensuing revenue reduction would be very small. Then, once FDI comes in and the industry starts growing, public revenue will even increase. Implementing such an approach will have a positive demonstration effect and eventually make it easier to correct other distortions. Such a pragmatic approach of giving targeted industries a good enough business environment allows some developing countries to grow dynamically in spite of poor overall business environment in their countries. Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam, offer powerful examples. Their Doing Business Indexes in 2012 are respectively, 126, 91, 132, 129, and 98, among the lowest in the ranking.

That is why I have been calling for a third wave of development economics—after early structuralism (Development economics 1.0) and Washington Consensus (Development Economics 2.0). That new wave should be encouraged and motivated by the success of increasing numbers of developing countries in Asia and other parts of the world, and seek to refine structural analysis and bring back to the agenda some of the specific aspects of the process of economic transformation.

Let me now go back to some of the specific points made by Shanta, Kalpana, and Indermit. We are in broad agreement on the urgency of reform and the need to constantly rethink economic theory and policy. But we disagree on why certain interventions failed to stimulate sustained and inclusive growth, and what should be the proper division of responsibilities between states and markets. Most precisely, I do not share what seems like blind faith in the reforms proposed under the label Washington Consensus of the 1990s, which Shanta claims failed largely because national level policymakers did not buy-in to them and because corruption and vested interests blocked any hope of enduring reform. African countries have implemented many other policy packages designed abroad—including socialist policies and import substitution strategy advocated by structuralism.

The failure to embrace wholeheartedly the first-best reform proposals in many developing countries was not necessarily due solely to the capture of the vested political elites and a lack of domestic political consensus. It was also faltered because government interventions were deemed necessary for protecting non-viable firms in the “priority” sectors created under previous strategies. The removal of government protection would have led to the collapse of those firms, created large unemployment and social instability or the loss of precious foreign exchange and fiscal revenues. Therefore, even in countries with consensus to remove those distortions, such as Russia, other CIS and Eastern European countries, governments often reintroduced disguised forms of protection and distortions, which were even less efficient than the original policy measures. That is why CIS and the economies of Central and Eastern Europe that attempted the so-called “shock therapy” performed more poorly than those like Belarus, Uzbekistan, and Slovenia, where a more gradual approach to reform was adopted. An even better way to carry out reform is the dual-track approach invented by Mauritius in the 1970s and followed by China and Vietnam in the 1980s, which allows policymakers to reduce political resistance for reform and achieve stability and dynamic growth simultaneously.

My view is that the sharp distinction between Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire stressed by Shanta is mainly rhetorical: more than 50 years after their independence, both countries are still undistinguishable from an economic standpoint; they are still poor, with per capita income levels of $1,230 and $1,160, respectively (WDI 2012). Ghana’s President Nkrumah was wrong not because of his belief that the government had to play the facilitating role to overcome market failures in structural transformation, but in his attempt to implement a comparative advantage-defying strategy. His was a common mistake among most developing countries in the post WWII era. They were influenced by the structuralist developing thinking and Soviet Union’s experience at that time. The economic strategy underpinning Ghana’s Second Development Plan, launched in 1959, aimed at modernizing the country through the development of advanced high capital-intensity industries in record time. Rather than trying to build a “modern” industrial sector centered on heavy, capital-intensive industries in the late 1950s, he should have facilitated private sector-led labor-intensive industries in which Ghana had comparative advantage.

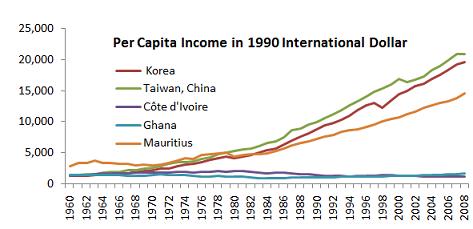

Likewise, the celebration of President Houphouet-Boigny’s economic strategy in Côte d’Ivoire is misleading. The country did enjoy two decades of rapid growth after independence in 1960. However, without government facilitation, its economy did not undergo structural transformation. After years of dynamic growth, its economy’s exports remained predominately agricultural products, like coffee, cocoa, palm oil, sugar and pineapple. Such a lack of diversification had three drawbacks: First, growth was never inclusive and inequality between a small elite and a majority of the population increased dramatically, as shown by several World Bank empirical studies by Lionel Demery. Second, due to the lack of diversification, its economy was not resilient to the external and natural shocks. The world recession and a local drought trapped the Ivoirian economy in economic crises, leading to a period of tumult in the 1980s followed by civil war. Third, as shown in the figure, Cote d’Ivoire’s economic performance in the past five decades has been rather mediocre compared to other economies, which had a similar starting point but whose governments played a facilitating role to diversify and upgrade their economies accordingly to their comparative advantages.

Source: August Maddison, Historical Statistics of the World Economy, 1-2008AD

I agree with Shanta’s observation that the first wave of development thinking was disappointing. But I do not share his assessment of the reasons for the failure of the Morogoro shoe factory in Tanzania. The East African economy has one of the highest cattle populations in Africa and the potential for a thriving leather sector does exist there. Shoe is a labor-intensive industry, which Tanzania has comparative advantage in, based on factor costs of production. There is no need to use rents to support its development. The company did not manage to export its products because not only it was state-owned and poorly managed, but also because it had little access to international marketing channels. Moreover, there was no cluster in the shoe industry, which increased the logistical and other transaction related costs. Tanzania can develop shoes by attracting FDI through a cluster-based industrial park approach. In fact, despite its many policy distortions, Ethiopia is currently developing its footwear subsector with some success in a private sector-led, government-facilitated leather industry, which has the potential of creating up to 100.000 new jobs in the medium term.

Unlike Shanta, I do not believe that the recent acceleration of economic growth in Africa from about 3 percent a year to almost 6 percent a year is due to the implementation of Washington Consensus policies “that they emerged from a domestic consensus.” While macroeconomic stability is certainly an important factor, the improvement in the growth performance in many African countries can be attributed to the global commodity boom and the improvement of macroeconomic stability is a result of the growth performance. A simple cross-country regression shows that the most important parameter explaining the growth performance in Sub Saharan African countries is the resource intensity of the country. The business environment and its improvement do not have a consistently significant effect on growth performance. In fact, their signs even show their effects likely to be just the opposite.

Moreover, the claim that infrastructure and skills deficit explain the lack of structural transformation is not supported by empirical evidence. Several African countries—such as Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Cameroon, Senegal, and Kenya—did not exhibit these severe human and physical capital constraints. Yet structural transformation did not happen there spontaneously either. Even more to the point is the fact that structural transformation did not happen spontaneously in Tunisia and Botswana, although both countries have very good business environments. By contrast, China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Brazil, and India have achieved remarkable structural transformation and growth in spite of poor business environment ratings. They were able to undergo significant structural change because their governments played a facilitation role in the process of their economic development.

The lessons are clear: A country with poor business environment does not have to wait until all the distortions/interventions are removed before it takes off. However the caveat is that it should pursue targeted industries that are consistent with comparative advantage and the government should proactively help overcome the inherent coordination and externality issues in their growth. Many distortions certainly result from political capture (the transportation monopoly in Shanta’s example), the need to protect/subsidize non-viable firms (financial repression) or to generate revenues (the high tariffs for importing cars). Pragmatism is crucial in such environments. Political leaders always have some discretionary powers and are not necessarily hostages of elite capture. The key to success is to use those discretionary powers in areas where they can achieve quick wins.

I agree with Kalpana’s assessment that in South Asia increasing product variety, inserting producers into global production chains result basically from self-discovery. But she underestimates the scope and importance of proactive government support to create the conditions for their success. The booming of India’s IT industry was in part due, among other things, to strong government support, including large investments to improve land-based telecommunications. Likewise, Bangladesh’s vibrant garment industry also started with direct investment from Daewoo, a Korean manufacturer, in the 1970s. The whole process was facilitated by the government, which set up well-equipped export processing zones. After a few years, substantial knowledge transfers had taken place, and Daewoo’s investment was a sort of “incubation.” Local garment plants mushroomed in Bangladesh, with most of them traced back to that first Korean firm.

However, I disagree with Kalpana’s conclusion that the role for the government is not the strategic selection of industries and should be limited to investing in “public goods of a multi-purpose, multi-beneficiary and contestable nature (e.g., roads)”. The reason is that government resources are limited, especially in developing countries. They must be used strategically to produce the biggest economic impact. The government should facilitate entry to and help scale up sectors that are self discovered by private sectors by tackling coordination failures, as in the case of improving land-based telecommunications in India’s information service industry. However, the spontaneous structural change by private sector’s self discovery may not be sufficient for generating dynamic structural change and job creation. India’s information service industry employs about 8 million workers directly and indirectly. Its manufacturing sector employs about 10 million workers. In contrast, China’s manufacturing sector employs 85 million workers, although both countries have a roughly similar population size and started from a similar agrarian basis and income level 30 years ago. Shouldn’t South Asia and other regions learn from China and other East Asia economies for proactively facilitating their industrial diversification and upgrading?

The reluctance of most economists to endorse the government’s strategic selection of industries is because of the issue of “how to do it right”, for which the six-step Growth Identification and Facilitation (GIF) approach in the chapter 3 of my New Structural Economics book attempts to address. The approach is based on the idea of comparative advantage and combines the government’s strategic selection (Step 1) and the private sector’s self discovery (Steps 2-4). In countries with a large infrastructure deficit, a cluster-based industrial parks approach or carefully selected and located special economic zones as discussed in Step 5 of the GIF are often good instruments to circumvent national infrastructure deficits and politically entrenched distortions. While I agree with Milton Friedman’s admonition that “nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program,” I also believe that modest and time-limited tax holidays discussed in Step 6 of the GIF for incentivizing first movers in the latent comparative advantage industries identified in the step 1 of the GIF are not hard to phase out.

Indermit quotes Amartya Sen, who observed that the decades of economic planning illustrate both “horrendous over-activity in controlling industries, restraining gains from trade, and blighting competitiveness, and soporific under-activity in expanding school education, public health care, social security, gender equality, and land reform.” In fact, these are all symptoms, or proximate causes, of failure. Most of them were the result of adopting a comparative-advantage defying (CAD) strategy. When firms in the chosen “priority” sectors are inconsistent with comparative advantage and therefore nonviable, governments need to subsidize/protect them through various distortions, which results in over-activity in controlling industries. Health care, social security and other important sectors of social development are neglected because poor economic performance leads to small levels of public revenues, especially when limited public resources are mobilized to subsidize the needs of the CAD sectors.

I do not share Indermit’s view that a noticeable shift in development policy in the 1980s and 1990s (with governments reducing their control of industry, embracing trade, and increasing their attention to education and health and social security) led to “a surge in development—especially in Asia and Europe.” The issue of reform is not only the direction of reform, but also the scope, pace and sequencing of reforms because the countries are not operating in a first-best environment but Nth-best world. Yes, Brazil, India, and China as pointed out by Indermit all reduced government intervention and moved toward market economy. But they adopted a gradual, dual-track approach, liberalized state interventions for those sectors with comparative advantage, while retaining distortion/interventions for firms in the old CAD sectors. That dual-track approach, which in the 1990s was considered by many economists the worst possible transition approach and would lead the country to a disastrous consequence, allowed them to achieve stability and dynamic growth simultaneously. By contrast, those Eastern European and CIS countries that adopted the Bretton Woods institutions’ shock therapy encountered transition collapse and long stagnation and went through lost decades in 1980s and 1990s. Their economic rebound in the 2000-2007 reflected the recovery from the collapse, and the large inflows of cheap capital from the financial liberalization, which explains why the Europe and Central Asia region was hurt the most during the recent global crisis.

Summarizing areas of policy agreements among development economists today, Indermit notes the importance of fiscal and monetary discipline, the reliance on markets, and the benefits of trade. But whether these policy goals are achievable is a matter of endogeneity: a country that adopts a comparative advantage-following (CAF) strategy or a dual-track transition approach to reform will achieve these goals because of innate competitiveness and strong growth performance. But countries that adopt a CAD approach and shock therapy will not prosper, because their growth will falter and they will be forced to subsidize/protect their non-viable firms, in explicit or disguised ways. The need for a competitive exchange rate, liberalization of foreign direct investment, and well-executed privatization of public enterprises, which Indermit also identifies as a topic of policy consensus among development economists, really corresponds to a first-best world. Again, the strategic policy challenge facing developing countries is how to move from the Nth best world to the first best. While I agree with Indermit that government interventions in pursuit of CAD strategies are misguided, I also believe that the generic Washington Consensus-type of policy prescription to simply move away from facilitating structural transformation (a prescription based on past failures of CAD strategies) amounts to throwing the baby away with the bath water.

I appreciate Indermit’s acknowledgement that I believe in new industrial policy because I have seen up-close the workings of a very capable government. But it has not made me forget my training of economic history at the University of Chicago, which I cherish. It has made me understand that in the catching up stage from an agrarian to an industrialized and most technologically-advanced economy in the world, the US government played proactive role in the structural transformation of the American economy. Long after the catch up, the US government continues to play a proactive role in facilitating technology and industrial innovation through patent, support for some basic research, procurement schemes to specific firms, and mandates. Except for patents, the other policy measures used by the US government actually correspond to picking winners.

Moreover, one should not forget that development economics deals with challenges in to developing countries. Appropriate policies and institutions in such countries may be different from those of advanced countries. One common mistake among many is the suggestion that developing countries must develop large national commercial banks and equity markets similar to those in the developed countries, neglecting the needs of financial service, especially lending, of small firms and household in manufacturing, services and agricultural sectors. Being a good chief economist is not to be good preacher of what we learn from the textbooks at the University of Chicago or elsewhere, which mostly depicts the first-best scenarios based on the experiences in advanced countries, but to understand the opportunity and challenges in any given context and propose policy changes in Nth-best situations in developing countries.

Finally, I very much like Deng Xiaoping’s quote in Indermit’s piece, but I read it differently. He seems to emphasize the last sentence, that “In the course of expanding production in the United States, a wealth of experience has been gained from which others can learn.” What Deng actually means is that China can learn insights from U.S. experience, not that China should copy its policies and institutions. It is unfortunate that development policy recommendations have too often attempted to copy what America is doing—not what it did when it was just another underdeveloped agrarian country on the world map. This is the reason why I highlight in my opening remarks the need to consider the difference in the level of development in considering the development policy. My hope is that this kind of intellectual exchange with colleagues and fellow researchers help us discover the Holy Grail of economic progress.

------------------

Join the Conversation