“People want to work, not fight,” said Nadir Ali, a male shopkeeper in Kabul, Afghanistan, in one of the discussion groups of the Moving out of Poverty: Rising from the Ashes of Conflict report. For many, like Nadir, work is a crucial part of their existence. However, in many parts of the world conflicts and violence prevent citizens from working as they destroy communities, institutions, infrastructure and human capital. Not surprisingly, they represent a major challenge to job creation, as highlighted by the 2011 World Development Report (WDR) and the forthcoming 2013 WDR.

South Asia has experienced high levels of conflict over the past decade. More than 58,000 people were killed in armed conflict worldwide in 2009; at least a third of them were in South Asia.1 Ongoing conflicts in the region include the conflicts in Afghanistan and Pakistan, insurgent movements in India’s northeastern regions, and the violent activities of left-leaning groups in the eastern and central parts of India. Nepal and Sri Lanka are recovering from long-lasting civil wars. In a recent paper prepared for South Asia’s first regional flagship report "More and Better Jobs," we examine the key challenges to job creation in conflict-affected environments, using household and firm level surveys from South Asian countries.

Armed conflict affects the demand for labor by reducing both the incentives and the ability of firms to invest and create jobs. Almost 60 percent of formal firms in the World Bank’s enterprise surveys cited political instability as a major or severe constraint to doing business in South Asian countries. The other major issues cited were lack of electricity, corruption and other regulatory issues like tax administration. As we might expect, these constraints of security, infrastructure shortfalls and lack of effective regulation and governance were significantly higher for firms in conflict-affected areas.

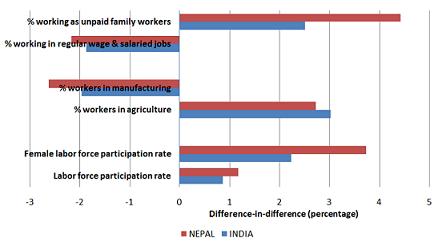

The constraints to firm activity are also reflected in the features of the labor market in conflict-affected zones. Labor force participation is higher in conflict-affected areas, particularly for women. However, workers in conflict-affected zones are much more likely to be employed in low-productivity agriculture, rather than in construction or manufacturing. The quality of jobs held is also poor: these workers are significantly less likely to be in jobs with regular wages and significantly more likely to report themselves to be working in the “informal sector” or as “unpaid family labor.” While some of these differences might have been present even before the conflict (e.g. conflict-affected areas typically have higher poverty rates even before conflict occurs), we exploit the spatial and time variation in conflict incidence within South Asian countries to find that most of these differences are actually exacerbated by the experience of conflict. For instance, conflict-affected areas in South Asia are slower to reduce their dependence on agriculture and experience a bigger increase in female labor force participation during the conflict (See Figure 1 for labor market differences across conflict and non-conflict zones for India and Nepal, computed before and after exposure to conflict).

Figure 1: Labor Market Differences between High-Conflict and Low-Conflict Areas in India and Nepal

Notes: The “difference-in-difference” estimate for Nepal is the difference in labor market trends between households residing in high-conflict areas and those in low-conflict areas between1996 (before the conflict) and 2004 (in conflict). This is computed as: (Outcome in high-conflict areas in 2004 – Outcome in high-conflict areas in 1996) – (Outcome in low-conflict areas in 2004 – Outcome in low-conflict areas in 1996). Difference –in-difference estimates for India are computed in a similar manner. See Iyer and Santos (2012) for further details and the definitions of high-conflict and low-conflict areas.

Labor supply is also affected by the presence of conflict. We find that the workforce in conflict-affected zones has significantly lower levels of formal education, though some countries (e.g. Nepal) have managed to maintain school enrollment even in the face of civil war.

What can policy makers do to spur job creation in conflict zones? The obvious first step is to bring an end to the conflict. This can yield a significant ‘peace dividend.’ A striking example is Sri-Lanka. During the ceasefire that lasted from 2002 to 2004, unemployment in the conflict-affected Northern and Eastern Provinces decreased by 4 and 5 percentage points respectively, at a time when the national unemployment rate decreased only slightly, from 8.8 percent to 8.3 percent. In the initial post-conflict phase, the strong constraints to private activity mean that public sector programs will likely play a large role. Efforts as disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs and broader-based public works are useful ways to spur job creation. The focus of such programs is likely to be on agriculture or other low-skilled sectors, such as construction. However, these programs can be fiscally costly: DDR programs in Afghanistan cost $2,278 per demobilized person, and $2,500 in Nepal; this is several times the average per capita income of these countries (Carames and Sanz, 2008 and 2009).

Policy makers should plan three important transitions from policies and programs over the medium-term: increasing the role of the private sector; refocusing attention from the agricultural and informal sectors toward facilitating higher-productivity employment in other sectors; and moving from targeted programs for vulnerable groups (such as ex-combatants, at-risk youth, war victims, and displaced people) to broad-based employment generation.

As part of these transitions, governments need to take steps to attract the private sector, such as reforming business regulations, issuing temporary tax breaks and forging public-private partnerships, so that the private sector can eventually become a more significant provider of jobs. International organizations and foreign governments have important roles to play in providing funding and building capacity in these early stages, particularly in cases of nationwide conflict. It is also important to realize that even in the early post-conflict period, community based interventions can be a useful complement to purely government-led initiatives, and the private sector can also be a significant contributor to job creation. In our paper, we discuss several examples of such initiatives, ranging from Afghanistan’s National Solidarity Program (which involves local communities in reconstruction and infrastructure provision) to Colombia’s private-sector training program for workers displaced by conflict.

Jobs and sustainable peace can positively reinforce each other, as long as programs and policies are inclusive and sensitive to the grievances that led to conflict in the first place. The fact that millions of new entrants will enter the South Asian labor force in the next two decades further increases pressure to create more and better jobs, especially in post-conflict environments and areas at risk of new or renewed violence.

1Data from the Institute of Strategic Studies. We focus throughout on internal armed violence against the state rather than inter-state conflict

Referrences:

Carames, A., and E. Sanz. 2008. Analysis of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration. DDR. Programmes in the World during 2007. School for a Culture of Peace, Bellaterra, Spain. http://escolapau.uab.cat/img/programas/desarme/ddr005i.pdf.

2009. Analysis of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration. DDR. Programmes in the World during 2008. School for a Culture of Peace, Bellaterra, Spain. http://escolapau.uab.es/img/programas/desarme/ddr/ddr2009i.pdf.

Join the Conversation