Kids drawing and learning (environment education concept) © shutterstock.com

Kids drawing and learning (environment education concept) © shutterstock.com

Addressing climate change requires individual behavior change and voter support for pro-climate policies, yet surprisingly little is known about how to achieve these outcomes. Despite the urgency and scale of the challenge, current efforts are underwhelming, in part because sizable populations around the globe remain skeptical about climate change and policies to tackle it.

How to overcome this resistance?

One promising approach is the accumulation of human capital through increased educational attainment. More educated individuals may be better equipped to understand the complexities of climate science and have more awareness of the risks of climate change. A recent global survey found that people with more education were more likely to see climate change as a major threat. More education might also yield transferable skills across occupations, encouraging voting for policies that promote less-polluting industries, such as renewable energy subsidies.

Link between human capital accumulation on pro-climate beliefs and behaviors

People who choose to pursue more education are, by revealed preference, forward-looking and thus more concerned with the future consequences of climate change. It might not be education that is causing pro-climate beliefs and actions. Reverse causality is another challenge. Individuals who believe in climate change might choose to pursue more education to better adapt to a changing world.

Compulsory Schooling Laws (CSLs) legally mandate an increase in educational attainment, often by raising the minimum school leaving age. A new World Bank paper assembled a new database on CSLs to estimate the causal effect of human capital accumulation on a series of climate outcomes in Europe.

Countries in Europe enacted dozens of education reforms in the twentieth century, expanding the number of years of education legally mandated through CSLs. The paper analyzed 39 CSL reforms in 16 countries and identified reforms for which there is a strong first stage — that is, where an increase in required years of schooling by CSLs substantially increases average educational attainment, net of the time trend, rather than assuming all CSLs increase education, or that all individuals are affected by CSLs.

Europe also has large, harmonized multi-country surveys, enabling credible within- and cross-country analyses, with recent climate modules, added to the European Social Survey (ESS), which are also analyzed in the study. The ESS is conducted biannually across dozens of European countries using stratified random sampling with a total sample size ranging from 20,000 to 40,000 individuals per round. It is a large micro data set capturing information on a host of social issues and is harmonized over time and across countries. In 2016, the ESS introduced novel questions on climate outcomes, such as “how often do you do things to reduce energy use?” and “how likely are you to buy energy-efficient appliances?” Moreover, the ESS collected data on policy preferences such as “to what extent are you in favor or against using public money to subsidize renewable energy such as wind and solar power?”

Lastly, the paper also includes rich data on voting for green parties since 2002. Europe has a robust green party movement, which has an explicit environmental agenda. The paper codified a novel dataset of green party voting outcomes, enabling the identification of pro-climate voting behavior. It studied new climate outcomes which extend well beyond standard measures of beliefs and behaviors, also examining the highly consequential domains of policy preferences and voting.

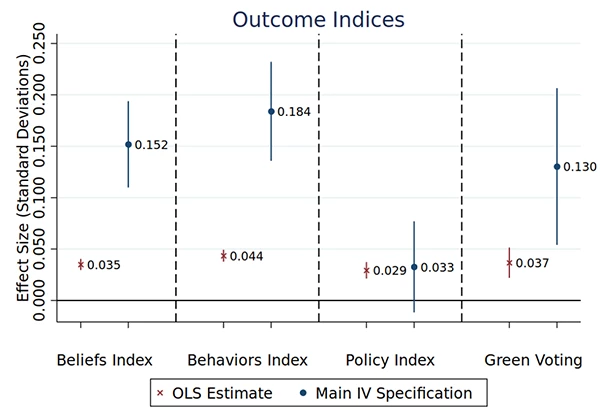

Significant impacts of education levels on nearly all pro-climate measures

Headline results show that an additional year of education leads to an increase of 4.0 percentage points (PP) in pro-climate beliefs, 5.8 PP in behaviors, 1.0 PP in policy preferences, and 3.6 PP in green voting.

Relative to status quo rates, these impacts are non-trivial, translating into a 6.3% increase for beliefs, 8.5% for behaviors, 1.7% for policy preferences, and a striking 35.0% increase for green party voting.

These results are notable since education has been conspicuously absent from most major climate change discussions. These findings suggest expanding general education should be added to the menu of approaches considered in tackling one of the greatest modern threats to human well-being. Indeed, human capital accumulation may be vital in shaping beliefs about the costs and benefits of policies to reduce emissions and extend directly to consequential outcomes such as policy preferences and voting.

Europe is a particularly relevant context since climate change is receiving substantial attention, including through efforts such as the European Green New Deal, yet education remains an underutilized lever. And there remains substantial room to expand education. While educational attainment has expanded dramatically in recent decades, the median school reform law in 2020 in Europe guaranteed only ten years of schooling, a full two years below a complete primary and secondary education of 12 years.

Implications for developing countries

These gaps are even more dramatic in the developing world; in Sub-Saharan Africa, educational reform laws only guarantee eight years of schooling on average. Expanding access to education has traditionally been believed to play a transformative role in the economic and social well-being of societies – it now also appears to play a vital role in the battle against climate change.

Join the Conversation