Many people working in development hope to `inform’ public officials. For example, academic research or the Bank’s own analytical studies often conclude with `policy recommendations’ to be taken on by individuals in charge of translating policies into practice, or public administrators. Yet what is the baseline level of knowledge of public officials that this work is building on? What do they already know and not know?

We investigated this question in Ethiopia by surveying a representative sample of 1,831 public officials across 382 organizations spanning all three tiers of government. We compared their estimates of key characteristics of their constituents to objective administrative and survey data to create a direct test of their knowledge. How did they do?

We start our blog with a quiz to you, the reader, to assess your priors on the accuracy of public officials in guessing the key characteristics of the local citizens that they serve.

The Basic Knowledge of Public Officials

In our new paper, we report on the collection of (some of the first) individual-level data on the information that public officials have about their local constituents. In a minority of cases, the public officials we study make relatively accurate claims about their constituents. Of officials’ assessments of the population they serve, 21.5 percent are within 20% of the census-defined population.

However, a large portion of bureaucrats make economically-meaningful mistakes in their tacit beliefs. The mean absolute error in education bureaucrats’ estimates of primary enrollment numbers is 76% of the true enrollment figures. The mean error in estimates of the proportion of pregnant women who attended ANC4+ during the current pregnancy (the ‘antenatal care rate’) was 38% of the benchmark data. Agriculture officials overestimate the number of hectares in their district that are recorded as used for agricultural purposes by almost a factor of 2.

Such large errors are consistent with studies of agents from other settings. However, in government such errors can have large economic consequences as they skew the distribution of public resources and change the nature of public policy. In our paper, we provide evidence that this tacit knowledge feeds into the allocation decisions of civil servants and that these errors are correlated with service-delivery outcomes.

Why Do Some Civil Servants Do Better?

Why do we see some civil servants making lower errors in their tacit beliefs than others? First we looked at education, experience in service, and other individual characteristics and find little evidence that this explains the variation we find. Similarly, characteristics of the local constituency (population, remoteness, poverty rate, topography, and road density) do not effectively explain the variation. Interestingly, the availability of technology does not explain much of the variation either. Together, there is little evidence that the cost of acquisition is the problem.

Rather, what we find substantial empirical support for is that civil servants who are given incentives to seek out and absorb information do so irrespective of the nature of that information. Public service incentives for information acquisition are the dominant determining factor of how informed an individual official is.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. A substantial economic theory literature (a key reference is Aghion and Tirole (1997)) has outlined for years that since information in the public sector requires effort to acquire, information is likely to be better in organisations that (1) give officials power to make decisions (de facto authority), and, (2) reward the collection and use of accurate information.

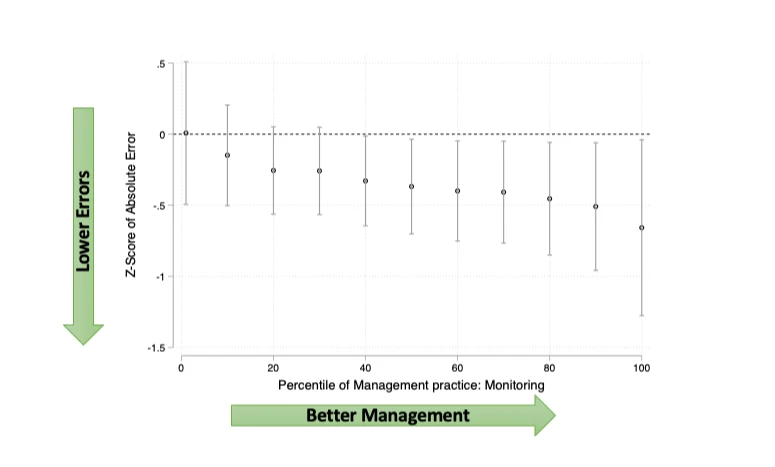

In our data, civil servants have significantly better information when they are given de facto authority (they now have an incentive to acquire accurate information as their decisions are not overruled by a superior). However, the incentives interact. The effect of authority only reduces errors when there are organisational incentives in place to use and collect operational information (see figure 1). Why bother acquiring information (perhaps at some cost to you) if no one will reward you to use it?

Figure 1: The Effect of De Facto Authority on Absolute Errors by Percentiles of Monitoring Management Practices (OLS Coefficients and 95% Confidence Intervals)

If the public sector doesn’t have the right incentives for acquiring information, is it any surprise that those trying to inform public officials often find it an uphill battle?

Let’s Just Make a Really Cool Policy Brief

The traditional response to struggles to inform public officials is to produce a briefing that is both informative but easy to digest. To investigate the effectiveness of top-down interventions like these, we ran a field experiment that distributed the exact information that we asked about to a random subset of organisations in a way that exactly mirrored civil service protocols. The information was sent through government circulars, reflecting the communication system in already place within the bureaucracy. Providing information in this way significantly reduced the cost of acquisition.

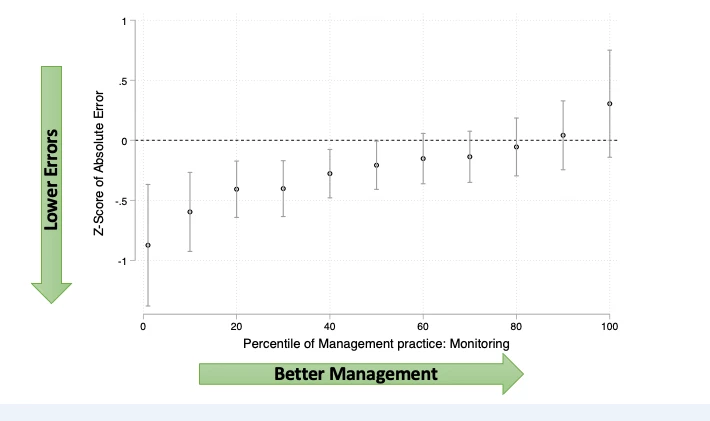

It worked. We find significant improvements in the information that civil servants have. However, public sector incentives once again mediated where we found impacts. Only in organizations where management practices are weak did the information provision have any impacts (figure 2). When incentives for information acquisition were in place already, officials had the information.

Figure 2: The Effect of the Treatment on Absolute Errors of Civil Servants by Monitoring Management Practices

This all matters in how we try and inform public officials. Fundamentally, if we could get public service incentives right in the first place, civil servants would actively search out information, making the life of a researcher interested in policy impacts easier. Where incentives for information acquisition are weak, this will understandably limit the information official’s collect. If we want informed public officials, they need the right organizational incentives to read our policy briefs.

Join the Conversation